Writing on Prepaid Time: Shannon Sanders on Balancing Parenthood and Publishing

"What I wanted, ultimately, wasn’t permission to write instead of parenting; it was to enter a fantasy world where there was time enough for both."

I write this the way I write everything: on prepaid time. For the next two hours, I’m sitting at a picnic table a few miles from home, where my three small kids are napping or playing under my husband’s loving and watchful care—and only because I’m here and not there can I actually hear myself think clearly enough to set words to paper. It’s like magic!

Notice the words I did and didn’t use—that the time is prepaid rather than borrowed; that the writing session is a trim two hours rather than however long it takes; that I was careful to let you know, through husband-modifying adverbs, that the kids have been left in their other parent’s excellent hands. For a number of infuriating but obvious reasons, I don’t want you to think I’m neglecting my children to write an essay. I’ll take it even a step further and explain what I mean by prepaid: It’s Saturday, and I spent the first half of the day—starting with the kids’ like-clockwork 6:20 a.m. wakeup—in service of small people and their demands. First the mad breakfast rush, and then a few practice rounds of the alphabet song, a trip to the farmers’ market where no one wanted to be confined to the stroller or to hold hands, and a social event on the playground at the twins’ nursery school. Also, out of consideration for my husband’s mental health, I’ll try to wrap up this session and get home before the end of naptime. I want you to know that I’m not stealing anything from anyone—even if my 5-year-old, as soon as I set foot back inside the house, demands to know where I’ve been all day.

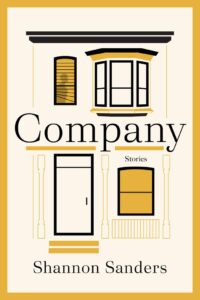

My husband, Wes, doesn’t understand why I care about any of that (he’s an incredible father, but he’s not a mother), but he accepts that I do. For Mother’s Day 2021—when our children were all under age four, two of them infants—he gave me the most thoughtful gift imaginable: a stack of 50 paper coupons, each worth one hour of guilt-free writing time. At that time, my corporate maternity leave was coming to a close and I was hard at work on the manuscript that would become my debut short-story collection, Company, which my agent and I intended to take out on submission later that year. He knew I needed the time.

*

Speaking of time: Doesn’t it play the funniest tricks? A real sense of irony, it has. Because a week before the world fell apart, I had one of the best days of my life. On a random weekday in early March 2020, a life-changing email arrived unexpectedly in my inbox. It was from literary agent Reiko Davis, who had recently seen that my first published story, “The Good, Good Men,” was a winner of that year’s PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers. Reiko wanted to know whether I was working on a book-length work, and whether I had representation.

It was impossible to fall into a groove when I knew I only had a couple of minutes left before it was back to the babies.

It was every writer’s dream, and happened at a brilliant moment. I had just started a new day job at a company that—unspeakable luxury!—would sometimes let me telework. My toddler was then part of a nanny share; we’d enrolled him to start nursery school a few months later. I was still riding high from that PEN award, and daydreamed constantly about all the time I’d have to write once he started school. I set my sights on my telework days, on all the time I’d reclaim by not having to commute to an office.

No, I didn’t exactly have a book-length work at the moment, but suddenly (cue heavenly harps) I saw a path to finishing one, and a reason to try. I was a fast writer, and normally my short-story drafts came together in a few days each. (Remember this fact when you consider my husband’s generous intentions in granting me hour-long blocks of writing time a year later.) Less than two years into parenthood, I was aware that finding time to write fiction—a hobby for me then, but also a lifelong passion just starting to shift toward center stage—was harder with a child. But as for the nuts and bolts, I was largely uninitiated: I hadn’t struggled much yet, hadn’t heard of the proverbial baby on the fire escape.

Reiko invited me to get in touch, which I did that very day. I described what I had in hand, which at that point was eight linked short stories I was proud of, most of them previously published in literary journals. We worked out a plan for me to add four more to that number—for a total of twelve, at least a third of them unpublished. I told her I could have it ready within three months.

Exactly a week later, my company switched to 100% mandatory telework. The nanny share disintegrated. The nursery school refunded our tuition deposit and shuttered for the coming year (and thank goodness, because we had to pay the nanny to stay home). Because my husband worked in healthcare, we carried outsize Covid risk (and had numerous potential exposures) and couldn’t call in help from grandparents or anyone else. We were healthy, but otherwise screwed.

You’ve read about—or know because you lived it—what life was like for parents at that time. It was about survival and nothing else. Very much not about writing stories and trying to assemble a cohesive collection.

This is how I found out the secret to my own former productivity as a short-story writer: I’d been doing most of the coarse planning in the quiet of my mind, during my Metro or highway commutes or while stapling papers together. The words came easily when I sat at my computer after hours of downtime spent planning. Working outside the home full-time while raising a toddler is not easy, but with adequate childcare, it isn’t impossible; it includes occasional small pockets of downtime. Waiting for the coffeemaker in the break room, or en route home from my office, I was off the hook. At least until I walked in the front door, and then all bets were off. Toddlers don’t respect the quiet of your mind. My work as an attorney takes focus, but it doesn’t demand it the way parenthood does. It doesn’t grab me by my chin and ask, at a distance of three inches and with Cheerio breath, whether we can go outside right now to follow the garbage truck around the neighborhood.

I’d promised Reiko a draft of my collection by June 2020. I had planned to add four stories, which in my previous life would have taken me anywhere from four productive days to four dreamy weeks of mentally drafting on the subway. But without a commute, without childcare, without even one nanosecond of solitude, I blew right through that self-imposed deadline.

And then I found out I was pregnant with twins—the pregnancy planned, the twins a shock. The seven brain cells I’d had available for things other than keeping my toddler alive evaporated overnight, or maybe I vomited them out. Sometimes I had to lie down on the chenille mat while bathing my son. I could barely perform my day job. Thus it took me well more than a year to add the needed four stories to the collection, to get it editor-ready. A year in which many things happened (including the tripling of our number of offspring)—but none of them concrete steps toward achieving my lifelong dream of publishing a book.

This is how I became initiated. This is when I started to wonder why our townhouse didn’t have a fire escape.

*

I tried a number of things suggested to me by other writer-parents, but none of them worked. Write while the kids are asleep was the most common suggestion—but it wasn’t feasible; if the newborn twins’ sleep schedules fell off sync by even 15 minutes, there was no childfree hour all night long, including for my own sleep. Another was to use voice-to-text memos to seize ideas before they were forgotten—but while nursing my singleton newborn had allowed for that kind of thing, tandem twin nursing occupied my whole body, including both hands. Nothing was going to work except to magically add hours to the day.

Enter my husband’s gift, the stack of coupons. It was my first Mother’s Day as a mom of three, including three-month-old twins. The idea was that I would periodically cash in a coupon, excuse myself to our Covid-safe back porch, and crank out one hour’s worth of material in furtherance of a finished draft. He would, meanwhile, entertain our toddler, feed our babies bottles of pumped breastmilk from the freezer, and otherwise hold down the fort while I worked on my manuscript.

Wes’s intentions were pure, and I don’t think he could have done more to support my dream. Even though traditional publishing was a part of my plan—meaning that I hoped my work would eventually bring money into the house, some of which I would reinvest in my writing and the rest in our family—there was nothing transactional about my husband’s gift. He wanted me to have time to write because he knew I loved to write. Also, I was a leaky, sleep-deprived mess; he could see that I needed the breaks. It was extraordinarily generous and kind of him.

I kept a loose Twitter record of my coupon use so I could look back on it later. The tweets span approximately eight months (from May 2021 through January 2022) and are, at best, half-honest. When I read them now, I can see my own agenda at work: I wanted to show my husband—and anyone else paying attention—that the time was being well spent. Sometimes that meant sprints of drafting, sometimes marathons of internet research, sometimes engaging in the tedious business of publishing. Writing can mean lots of things, and not all of them are writing. Overall, though, the tweets tell a story of pushing my collection toward completion.

But in real life, nothing was nearly that simple.

First of all, a sliding-glass door—like the one that separated our townhouse from the back porch where I was meant to do my writing—is not an impermeable border. Visible children do not make for mental distance. I could see and hear everything they were doing, every tiny spill (liquid or body). An hour shrinks down quickly when one spends 35+ minutes running in and out of the back door staging interventions.

In the end, you can tell that I quietly gave up on using the coupons in a pure sense.

Second, breastfed babies don’t care about coupons. And at the risk of oversharing, neither do lactating breasts. Even in the very early days of my coupon-cashing—when Wes was still game to let me have the time without strings attached—my sessions were repeatedly interrupted by leaks and letdowns, many of them brought on by the sounds from the other side of the glass door. Sometimes Wes would bring me a baby to hold while he prepared a bottle, simply because he didn’t have enough hands to juggle all three of the kids and the frozen milk. Often, I’d decide to just go ahead and feed the baby.

(I did plenty of typing one-handed with an infant staring at me, onyx-eyed and milk-drunk. But—and here was something else I hadn’t expected about the collision between real life and my collection-in-progress—my parent mind struggled to find its way back to its previous form, the one responsible for the original draft of the collection. By that, I don’t mean that new-mom hormones were clouding my thoughts, even though that’s true too. What I mean is that the book I was working on—the book I was proud of and wanted to see through to completion—was imprinted with the perspective of a woman who was not yet a mother of three small children. It was harder to maintain that perspective with an infant in my lap.)

Third, there was the fact that, as he put it, Wes wasn’t “a machine.” Initially, he told me I could use more than one coupon at a time. Great! Sometimes I’d hit my stride around minute 55 and inform him I’d be taking a second hour. But eventually, he told me the surprise extensions weren’t working for him—that I’d have to declare my intentions at the outset so he could prepare himself mentally. I understood: Solo stretches of caring for multiple little kids are hard on the body and spirit; they are much easier with an endpoint. But endpoints are antithetical to the writer’s flow state. It was impossible to fall into a groove when I knew I only had a couple of minutes left before it was back to the babies.

And finally, there was the simple fact that I didn’t want to miss time with my kids to finish writing my book. That fact creeps through in some of my tweets. They’re three amazing people, and I’d love to spend every second with them if my body and mind allowed it. What I wanted, ultimately, wasn’t permission to write instead of parenting; it was to enter a fantasy world where there was time enough for both.

In the end, you can tell that I quietly gave up on using the coupons in a pure sense. It’s okay; I finished the book in fall 2021, and Reiko and I sold it to Graywolf shortly afterward. The relief was similar to the final exertions of labor. In early 2022, the twins began sleeping for longer stretches—a momentous parental milestone—and without fanfare I switched over to working on my next book, a novel. My final tweets in the series thank Wes for his generous gift of coupons—by which I meant, his overall support, which shone through in the gesture, imperfect and impossible though it was.

*

After I cashed in my last coupon, there was no discussion of more. For the subsequent Mother’s Day, I was given a pair of earrings. That’s fine with me, because as the kids’ development accelerates, I’m less interested in missing even individual hours. The ones I spend at work, while they’re at school or with the sitter, are enough.

As I conclude this essay, I’m not at the picnic table anymore. That was a few days ago, and those two hours were enough to get me through the first half. I’m finishing up in the place where I do most of my writing these days: the desk in my own bedroom. The laptop I’m typing on sits inches from my closed work laptop. It’s 11 PM, and the kids have been asleep for three hours. The kids are five and two years old now; they sleep through the night every night unless they’re sick or there’s thunder. That means I can stay up late to enjoy some semblance of my own life. Once they’re down for the count, I can do a load of laundry or catch up on work or peck away at my novel.

And thank goodness: I’d like to complete this novel by a certain date, a goal I’ve set to lend structure to the enterprise. Nothing bad will happen if I don’t. And the kids won’t notice one way or another, because I’ll cook their dinners and read their bedtime stories either way. But if I do? What a win for everyone in the house.

___________________________

Company: Stories by Shannon Sanders is available from Graywolf Press.

Shannon Sanders

Shannon Sanders lives and works near Washington, DC. Her fiction has appeared in One Story, Electric Literature, Joyland, TriQuarterly, and elsewhere, and was a 2020 winner of the PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers.