50 Years Ago, One of the Gutsiest, Strangest Sci-Fi Movie Franchises Came to a Close with Battle for the Planet of the Apes

Matthew Hays on the Literary Adaptation (Yes, Really) That Doubled as a Hate Letter to America

Spoiler alert: This article is rife with spoilers from all five original Planet of the Apes films.

When Planet of the Apes opened in cinemas in 1968, its box-office success was surprising even to the filmmakers themselves. After all, the film featured an astronaut survivor named Taylor (played by Oscar winner Charlton Heston) facing off against a planet of actors wearing elaborate ape makeup.

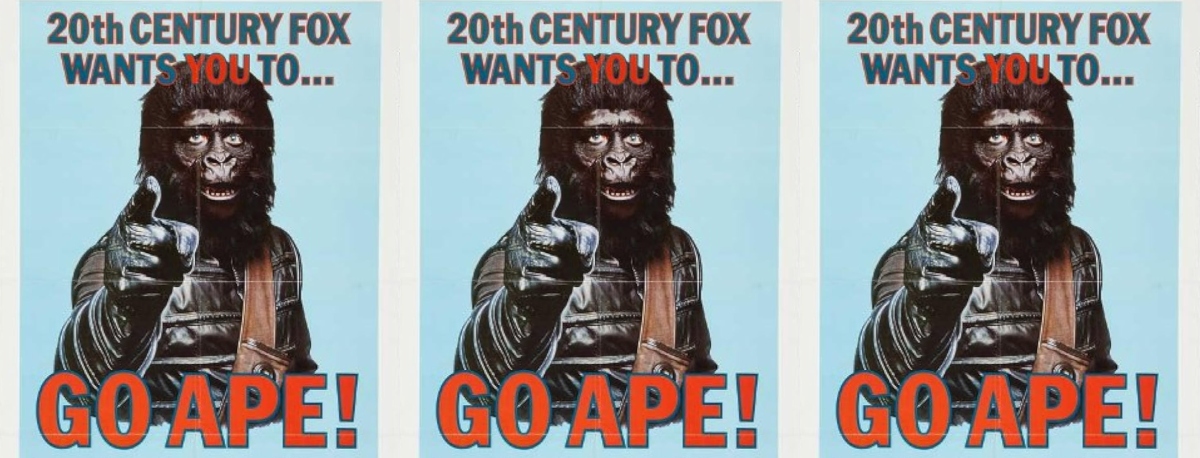

The possibility that the film would seem a giant joke to audiences had already crossed the minds of the suits at 20th Century Fox. The studio had set up an audience screening before they greenlit the project. Producer Arthur Jacobs was commissioned to film a 15-minute short film that would include some actors in ape makeup; if one person in the audience laughed, there would be no movie. No one laughed, and a legendary science fiction film was born.

To kids (I first saw the film at age six), Planet of the Apes seemed a basic movie about an astronaut landing on a planet run by a different species. But when the film arrived, many adults got the film’s multilayered jokes and running commentary: screenwriters Rod Serling and Michael Wilson (adapting Pierre Boulle’s novel) packed every imaginable bit of baggage that would fit into their carefully crafted Trojan horse. As New Yorker critic Pauline Kael immediately intuited, Planet of the Apes was a hate letter to America, full of commentary about slavery, manifest destiny, religious fundamentalism, creationism versus evolution, colorism and racism generally. The extensive medical experimentation done on the humans by apes is a clear reference to the Tuskegee Experiments. That some thought the apes were meant to represent Black Americans was a fundamental misreading of the film; the ape society is clearly a parody of American society, with all of its contradictions (especially the purported separation of church and state).

In a famous anecdote, at the film’s Hollywood premiere, Sammy Davis Jr. approached the producers, in awe of their achievement. He embraced each of them and congratulated them on what he declared was the most profound film Hollywood had ever made about racism in America. The producers all looked at each other, dumbfounded. They had no idea what he was talking about.

And neither did many who flocked to cinemas to see POTA, which became a sensation, in part due to its zany premise but also for its ending, one of the most shocking in film history: after escaping the apes and fleeing on horseback with his beloved mute girlfriend, Nova (Linda Harrison), Taylor curses his discovery of a half-buried Statue of Liberty on the beach, realizing he’s actually back on earth centuries after a nuclear war destroyed his planet Earth. It must have been one helluva nuclear war, as one observer noted, as the Statue of Liberty ended up on the west coast.

The gamble had paid off. But why let the profits end there?

Twentieth Century Fox

Twentieth Century Fox

Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970)

Fox execs began asking the creators of the original to begin cooking up ideas for a sequel. Heston was extremely uncomfortable with the idea, lamenting that one of the original scripted endings to the film—in which Taylor and Nova were shot and killed by the apes—hadn’t been adhered to. He refused to return in a starring role, but because he liked the first film so much, he offered them three days of his time.

By this point, a rough screenplay had been hatched, in which Taylor and Nova had discovered humans disfigured by radiation living in the remains of New York City, which was now completely underground. Just to prove they had chutzpah, Paul Dehn and Mort Abrahams granted the humans psychic powers, and the ability to inflict pain on regular humans simply by thinking about it. Oh, and in another twist worthy of Stanley Kubrick, the humans have a giant nuclear bomb in their church, which they worship with songs and chants. The humans wear masks, and when they worship the bomb, they reveal their actual selves by peeling them off, revealing that their faces are covered in exposed veins. Whoever cooked all of this up must have been baked.

The central character of Taylor (Heston) was replaced by Brent (James Franciscus), who has the bad luck to be assigned by NASA to follow in Taylor’s trajectory and try to find out what happened to the ill-fated crew of the first spaceship. (In sci-fi fanboy lingo, “Franciscus” has come to mean an actor who is replacing another actor of higher status and fame.) Brent crash lands in the film’s opening, his skipper dies, and before anyone can say “epic coincidence” he bumps into Nova, who takes him to Ape City, where he meets Zira and Cornelius. He then tries to track down Taylor by escaping into the Forbidden Zone, where he stumbles upon the underground city run by nuclear-radiated mutants, and meets up with Taylor in mutant prison.

As New Yorker critic Pauline Kael immediately intuited, Planet of the Apes was a hate letter to America.

This was arguably the most over-the-top of the Apes cycle. The humans worshipping the bomb as an instrument of peace could be seen as eerily prescient: by the 80s, the religious right was justifying its support of President Reagan’s massive nuclear build-up by suggesting such military might would maintain the peace. This entry in the film franchise is a particular favorite of mine because of its outright weirdness; it was a pleasing surprise to me when I interviewed Oscar-winning filmmaker Guillermo del Toro and he also said Beneath was his favorite entry, due to the WTF aura hanging over the entire affair.

One of Heston’s demands, upon reading the screenplay, was that he would be the one who would get to press the button that unleashes the nuclear bomb that destroys the planet. That way, he surmised, there could be no possible sequel. Planet gone, franchise over.

Silly, naive Chuck Heston! Where there are profits to be made, there will be sequels. You can’t keep a good franchise down.

Twentieth Century Fox

Twentieth Century Fox

Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971)

Despite mixed reviews, Beneath made as much money as the first film, and within months, Paul Dehn received a four-word telegram from Fox: “Apes exist, sequel required.” The question, of course, was how? The entire freaking planet and everyone on it had just been blown up in the final scene of the last film—and the producers had in fact intended that to be the end of the Apes movies.

Given that the movies were already trading in the idea of time travel, someone homed in on the fact that the spaceship Taylor arrived in from the first film could have somehow survived. What if the chimpanzee couple from the first two films, Cornelius and Zira, somehow managed to repair the ship, and take off in it before the earth blows up at the end of Beneath, and then get shuttled back in time to Earth in the early 70s? It sounded just ludicrous enough to somehow get greenlit, perhaps because such a premise would mean no elaborate sets would have to be created (the spaceship lands on the coast conveniently near Hollywood) and only a few actors would need to don ape makeup. Think of the savings!

Whoever cooked all of this up must have been baked.The opening of the film was intended to be as shocking as the closure of the first: a ship is pulled out of the ocean by American soldiers, and three astronauts are plucked out of it. The military officers on the beach assume they are human and begin to salute them, as the astronauts shock everyone by removing their helmets to reveal they are, in fact, apes.

As insane as it sounds, Escape is a remarkably solid entry. Oscar-winner Kim Hunter, as Zira, and Roddy McDowall (who would reprise his role as Cornelius from the first film after having to skip out in Beneath), are touching as the survivors of the planet, who win over the public with their wit and charm. Their fondness for each other makes the first third of the film uplifting. But then things take an incredibly dark turn: an evil McCarthyite adviser to the President (Eric Braeden) drugs Zira and gets her to describe in detail the kind of scientific experimentation the apes performed on humans. He records this interrogation and plays it back to a government committee: if the apes are allowed to procreate, they will create more talking apes, and in the future they will come to dominate the planet and oppress humans. The apes must die!

Escape then spirals into a brutal, extended chase, in which Cornelius and a very pregnant Zira flee into the forests of California, only to be hunted down by the army who finally execute them and their newborn baby. I remember being traumatized as a child when first seeing this devastating scene.

But the couple managed to switch their baby chimp with a different one when they were taken in by a traveling circus; the talking baby chimp lives on, uttering his first words in the final moments of Escape.

The third entry must be given some credit: it’s entertaining and somehow managed to reboot what seemed an unrebootable series, while setting the stage for entry number four. The plot twist of the apes finding and repairing the spaceship from the first film is so incredulous that some fanboys filled the gap with a crossover explanation: a 2014-15 five-part graphic novel series, Star Trek/Planet of the Apes: The Primate Directive, imagines the crew of the USS Enterprise helping the apes repair the ship and teaching them how to engage in time travel.

Twentieth Century Fox

Twentieth Century Fox

Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972)

The baby from Escape has now grown up into a very angry young chimpanzee, Caesar (played by Roddy McDowall). The setting is Los Angeles, 1991, when apes haven’t yet learned how to speak but are now an underclass of slaves, owned and sold by humans. Caesar can speak but must keep this a secret, for his existence as the surviving child of Cornelius and Zira has become urban legend. All cats and dogs have been wiped out by a plague, we learn, thus apes have become a hybrid of slaves and pets.

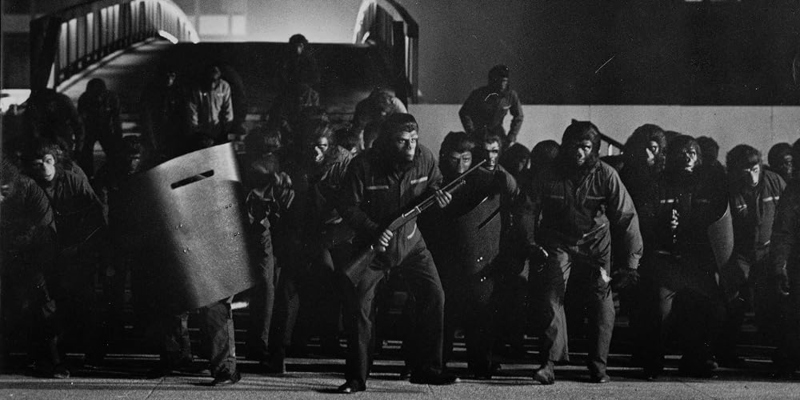

Caesar is interrogated by suspicious human officials, but in a clear nod to the film’s allegorical allusions to slavery, a Black human character named MacDonald (Hari Rhodes) helps Caesar escape confinement. Caesar goes on to lead his fellow apes in an uprising, teaching them how to use weapons and overtake their human masters. The film ends in a scene in which Caesar addresses his army of apes, who have emerged victorious and taken over the city once run by humans. He screams, “Tonight we have seen the birth of the planet of the apes!”

This entry pulls the series’ racial allegories into greatest focus, with its depiction of the cruelty and inhumanity of the institution of slavery. The riot scenes were modelled after the Watts race riots of 1965.

Twentieth Century Fox

Twentieth Century Fox

Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973)

The final entry in the series is perhaps a bit disappointing. It feels almost anti-climactic, and it’s clear the screenwriters knew they had to wrap things up. The uprising depicted at the end of Conquest culminates in another nuclear war, and in the aftermath, the apes remain victorious.

We catch up with Caesar a few years later, and it’s clear he’s been very busy: he now has a wife and young son, and has managed to teach all of the other apes to be fluent in English. The apes live in a city much like the Ape City we see in the first film, but humans live alongside them as a subservient class. The inequality is made clear early on: an ape may say no to a human, the unwritten rules of this ape-dominated society indicate, but a human may never say no to an ape.

For all of its occasional clumsiness, and for all of the sometimes-cheeseball effects, the POTA saga is incredibly impressive.Perhaps the funniest thing about Battle is a couple of the star cameos. By this point, playing an ape seemed to have a similar cachet as playing a villain in the 60s Batman series. John Huston plays the lawgiver, who tells the story of Conquest in a flashback that frames the film. And famous singer/songwriter Paul Williams appears as orangutan Virgil, Caesar’s closest confidant and advisor.

As there is discord between the apes and humans (in particular, some of the more militaristic gorillas, who really, really hate the humans), there is also an underground city of nuclear-radiated humans, ready to take their revenge on Caesar. Caesar must lead his apes in war to defend their city from the furious humanoids from hell.

Caesar prevails, but there’s plenty of carnage. And when the dust settles, the humans insist that everyone in the post-war society must be accepted as equals. Caesar agrees, and thus the series ends on this incredibly utopian note: that children of different species and races might one day be able to get along.

For all of its occasional clumsiness, and for all of the sometimes-cheeseball effects, the POTA saga is incredibly impressive. As critic Michael Atkinson notes in his homage to the first five films, “It’s one of the few science fiction movie texts that rivals in sophistication the best SF literature… the Apes films stand as the scariest, ballsiest, most breathtaking essay on racial conflict in film history.”

*

References and recommended reading:

Planet of the Apes Revisited, by Joe Russo, Larry Landsman and Edward Gross (Thomas Dunne Books, 2001).

Planet of the Apes: An Unofficial Companion, by David Hofstede (ECW Press, 2001).

Planet of the Apes as American Myth: Race, Politics, and Popular Culture, by Eric Greene (Wesleyan University Press, 1996).

Ghosts in the Machine: The Dark Heart of Pop Cinema, by Michael Atkinson (Limelight Editions, 1999).