Writing on an Island at the End of the World

Nell Stevens Chases Her Novel to Bleaker Island

In early scenes of Ryan Murphy’s film adaptation of Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love, Julia Roberts gets up in the middle of the night and prays to God to tell her what to do. She is unhappily married and wants to travel the world. Her husband doesn’t understand her. She is stifled by her successful life in New York. On her knees, she clasps her hands together so tightly her knuckles turn white. She says, Hello, God . . . nice to finally meet you. I’m sorry I’ve never spoken directly to you before, but I hope I’ve expressed my ample gratitude for all the blessings you’ve given [pause] to me in my life.

I know every single word of this scene by heart.

I know this not because I am a fan of Julia Roberts, or Ryan Murphy, or Elizabeth Gilbert. Rather, it’s because Eat Pray Love is the only film I watch in the Falklands.

I didn’t plan to spend my fellowship studying, intensely, the story of “one woman’s search for everything,” but before I left home, I was incapable of imagining a world without Netflix, and so didn’t think to prepare a supply of entertainment. Eat Pray Love happens, by complete coincidence, to be the only film I have on my computer—a lightweight laptop with no DVD drive. The idea that there would be no way to stream video in the Falklands did not cross my mind before I left—let alone the thought of no high-speed wifi, let alone the spluttering, extortionate Internet connection that only works 10 percent of the time, and even then, barely manages to load text-only emails, or the topmost slice of a digital photograph.

When I realize my mistake, I panic. I make plaintive calls to my family, and send pleas to friends for suggestions. In Stanley there are places I can buy DVDs, but without a way to play them on my computer, they’ll be useless on Bleaker. I investigate the option of ordering a DVD drive online, but delivery to the Falklands would take weeks; not even Amazon can get to this remote corner of the South Atlantic in time. I optimistically buy The Graduate from iTunes, and get through scratch card after scratch card of Internet time before giving up, the film 2.3 per cent downloaded, an estimated 89 hours remaining until completion.

This is frustrating because I know it should not be as troubling to me as it is. I did not travel to the bottom of the world to watch films. I did not travel to the bottom of the world to spend a lot of time and money trying to acquire films to watch. I came here to write, and should therefore accept that for the duration of my stay on Bleaker Island, if I don’t want to write (or read, or sleep, or venture out for a walk in sub-zero temperatures along the shoreline), the thing I will be doing is watching Eat Pray Love.

“It’s the only film I have with me,” I tell Annabel, the archivist, a few days before I am due to leave for Bleaker.

“That’s wonderful,” she says. “It’s a perfect formula. You can write your own version.”

There’s a man in the archive reading room who is trying to research his family history. He has flown to Stanley from an island off West Falkland specifically for this task, and is filling the room with a distinctly agricultural smell. He looks up now in a way that suggests he’d prefer silence, but Annabel overrules him. She is familiar, it turns out, with the film’s plot. She wants to help me craft a kind of sequel.

“Make sure you’ve left someone behind who is heartbroken over you,” she says, “but tell him this is something you just have to do—for your art. Then, now, in Stanley, you’re in the eating phase. You have to stuff yourself for the next few days.”

I consider Stanley’s gastronomic offerings. Cans of out-of-date soup. UHT milk. Bread that arrives already mouldy. Everything is shipped around the world from England, except for the “fresh” produce, which comes battered and withered after a sea journey from Chile. I paid six pounds for a saggy, sad lettuce, before learning to do as the locals do: stick to vitamin tablets and artificial-fibre gel.

“What about on Bleaker Island?” I ask.

“You have to have a spiritual awakening. Wander around and pray in splendid isolation. Makes perfect sense.”

“What about the love part?”

Annabel stalls. I tell her I have a one-night layover in Santiago airport on my way home and she says, “Well then, there you go. In Santiago, you have to get it on.”

[Gasping. Tears.] I’m in serious trouble. I don’t know what to do. I need an answer. Please. Tell me what to do. Oh God, help me please. [Tears.] Tell me what to do and I’ll do it. [Pause, then, in a different tone of voice.] Go back to bed, Liz.

I would like to say that I don’t know why I have Eat Pray Love on my computer, but the truth is that I have a weakness for saccharine Hollywood films in which women with nice hair and no cellulite get all they want at the end, as long as all they want is a husband. This predilection has overridden my strong dislike of anything that resembles “self help,” which Eat Pray Love most definitely does.

That said, if I were given the chance to choose, consciously, a film to watch repeatedly for weeks on end, I like to think I’d pick something less embarrassing.

Maura’s prediction that I would be the only guest at the house during my stay in Stanley turns out to be incorrect. On the day before I am due to leave for Bleaker, a Swiss ornithologist arrives. He is staying a few nights only, then heading to a small, outlying island to the west to study the migratory behaviour of caracaras.

I am back in the large leather chair in the sitting room, reading again, when for a second time I overhear a conversation I’m not supposed to. The ornithologist is with Maura, asking her about thermal clothing, local birdlife experts, and some kind of radio equipment he is trying to track down in Stanley. I suddenly feel horribly underprepared for Bleaker. I have been in a state of anxious denial about my imminent departure.

“Who’s the girl who’s staying here?” the ornithologist asks.

So this is it, I think. This is when I find out what Maura thinks of me. I recall the bitter, defensive way she talked about Tony the linguist: a shady character, a spy.

“Oh, Nell?” says Maura. “She’s a young American authoress. She’s here writing a history of the islands. She works at the archives, but she spends most of her time playing on her Game Boy. Anyhow, she’s leaving for Bleaker Island tomorrow.”

I am amazed by this report, and it takes me a little while to make sense of it. This is what Maura has supplied to fill the gaps I have intentionally left in my accounts of myself. I would have thought the conversation she and I had about my work being fiction, about making things up, would have stayed in her mind, but considering how much time I have spent with Annabel in the archives, it is reasonable enough for her to think I’m working on a history book. “American” is surprising, but perhaps understandable since the fellowship paying for my trip is from Boston University, and my T’s sometimes sound with an American flatness that I struggle and fail to correct. The Game Boy, though, is the real mystery. A few minutes later, when the conversation has moved back to caracaras, I look down at the Kindle in my hands and realize the source of the confusion.

Later that night, I sit on the floor of my bedroom counting raisins. I have planned carefully for this moment. I have brought supplies with me from England, topped them up from the limited offerings of the West Store, and am now attempting final calculations. The strict baggage limit for the tiny red planes that transport people around the Falklands restricts how much food I can bring with me to the island. At Stanley airport, I will be weighed alongside my luggage; our combined weight will be used to calculate not only who and what is positioned where on the aircraft, but whether I’m allowed to fly at all. I scrutinize myself in the mirror to try to guess how heavy I am, then optimistically add a few more raisins to the pile.

There is no means of buying food on Bleaker Island. This is a fact both obvious—it’s an island, unpopulated except for the farm manager and the owners, who spend only some of their time there—and confounding. Everything I will eat while I am there must come with me when I leave tomorrow. If I had been better informed, I would have known that I could arrange for provisions to be shipped out to me during my stay, but by the time I learn this it’s too late: the shipping plans are made months in advance. Most visitors to the smaller islands like Bleaker come either in the warm months as part of fully catered organized tours, or are scientists on research trips with the knowledge and expertise of academic colleagues and institutions behind them. Not many—not any?—are writers who looked at a map of the world and thought, whimsically, how about going here?

I am worried about the food situation. Although I know I have enough to stay alive, it’s far from ideal, and I’m concerned that hunger will affect my ability to work properly. In Stanley, I’m too embarrassed to admit to my predicament, and insist whenever anyone asks that I have more than enough food to get me through my Bleaker stint. Somewhere in my mind, too, is the idea that this is supposed to be a challenge, that I wanted to get as far from my comfort zone as I possibly could, and the difficulty of feeding myself for the weeks ahead is part of the point of the trip.

I am surrounded by little heaps of sachets of powdered soup, instant porridge, granola bars, and boxes of Ferrero Rocher chocolates, which are a convenient combination of indulgent, lightweight, and calorific. I calculate the total calories of everything I can afford to bring, and then divide it by the number of days—41—that I will spend on the island. It works out that I will eat 1,085 calories per day. This, I tell myself, is definitely enough to survive.

Maura pokes her head round the door. “They’ve announced the times for tomorrow’s flights on the radio,” she says. “You’re leaving at nine.” She notices, then, the pile of food on the floor. She looks horrified. “That’s not everything you’re taking with you, is it?”

“Oh, no,” I say, smiling, attempting nonchalance. “No—the rest is already packed.”

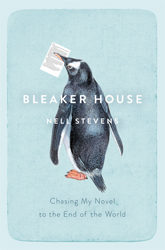

From Bleaker House: Chasing My Novel to the End of the World. Used with permission of Doubleday. Copyright © 2017 by Nell Stevens.

Nell Stevens

Nell Stevens has a degree in English and creative writing from the University of Warwick, an MFA in fiction from Boston University, and a PhD in Victorian literature from King’s College London. She is the author of the memoirs The Victorian and the Romantic and Bleaker House and is at work on a novel.