Writing Nature: The Healing Connection of Space and Spirit

Bridget Crocker on the Importance of Listening to the Voice of the Natural World

I grew up next to the Snake—a wild and willful river sourced from Pacific Creek on Two Oceans Pass in the heart of Yellowstone. I had a troubled childhood, marked by violence, poverty, and instability, and I found refuge among the cottonwood trees that shaded the riverbanks like gracious giants.

It was a place where I felt loved; the water skippers, frogs, deer, and moose who also frequented this pocket of shimmering forest welcomed me. I spent afternoons sitting next to the river, transfixed, until I felt I’d been absorbed by the river shore, blending into the willow saplings and granite stones rubbed smooth by the river.

It was in this state of complete surrender and focus on my surroundings that the clamor of my own troubles disappeared, and I began to make out the voice of the Snake River, who spoke to me in gurgles and words that flooded my mind with ideas separate from my own. Sometimes I even heard a voice speaking, despite the absence of other humans. I began communicating with the river, seeking comfort and letting the love I felt when I was with her lead me.

To live in community with a place creates a sense of collective coherence….The absence of it: trauma.

As a young woman, I became a whitewater river guide on the Snake, and I saw myself as the river’s steward and translator. I explained to the paddlers in my boat that the lodgepole pine stands alongside the river needed fire to regenerate, pointing out that their seed cones were coated with a resin that only opens during extreme heat. I shared with them stories I’d learned from the Shoshone about water babies coming to steal infants left unattended next to the river, never to be seen again, their cries the only sign of their existence.

“What does a water baby sound like?” My passengers asked.

“Listen.”

We’d float without talking, straining to hear water babies beneath the high-pitched rush of current passing over gravel bars. Boulders thunked beneath the deep, jade-green pools frequented by Brown Trout. Atop snags struck dead by lightning, ospreys built their nests; their sharp calls reaching us like cymbals over bass line.

I taught my clients how to hear the Snake, and they’d leave our two-hour trip knowing the river was alive, and they were in relationship with her. Everyone on the boat who’d felt the magic of the Snake was not only linked to the river, but also each other through collectively sharing this experience.

Thomas Hübl, the noted author of Healing Collective Trauma and the creator of the Collective Trauma Integration Process, wrote, “Space and Spirit are connected. When the space between us is full of alive presence, you have Spirit, or consciousness. When the space between us holds vacuums, or absence, you have trauma.” Hübl coined the term “collective coherence” to highlight what happens when many of a group’s participants become conscious of that space between them, as a result the space becomes potentiated for healing collective trauma.

In 2007, I led an exploratory river trip down the Subansiri River in Arunachal Pradesh, India. The region had only just reopened to foreigners since being cut-off from the rest of India and the bordering China-occupied Tibet since the early 1960s. As the foothills of the Himalayas, the region’s potential for hydroelectric power was unparalleled. For decades, China and India had waged skirmishes over the development of these rivers, making it unsafe for locals and foreigners.

My group was one of the first to run exploratory rafting trips there. We were met by tears of relief from the traditionally dressed older Adi people, who saw our entry as the end of the war and isolation they’d endured for most of their lives. We found Arunachal Pradesh to be a pristine wilderness, a land that time forgot. It wasn’t a stretch to see nature as divine here, with its glittering mica-flecked beaches touched only by civet tracks. Troops of deep forest monkeys escorted us through the mun zala rainforest as our group giddily traveled downstream. Fishermen—their boats filled with enormous golden mahseer—shared their bounty, and villagers tossed us sweet oranges from shore, taking care to feed us.

But on the last day of our week-long expedition, we saw something terrifying in its unnaturalness: concentric circles going upstream, caused by a repetitive pounding. A metal screeching overtook the sound of howling monkeys. We came around bend and haphazardly found ourselves in the middle of a dam site. The vibration of jackhammers pounded in our chests and bulldozers appeared from canyon floor to rim, gutting the Subansiri and hauling away her bones. The group sat immobilized by what we were witnessing—the killing of this emerald, waterfall-lined paradise that we’d all grown to deeply love.

Public outcry delayed the Subansiri dam from being completed for eighteen years. The fishermen and villagers who loved the Subansiri and her beautiful forests defended her. The relationship these defenders had with the river runs deep—not only in terms of sustenance, but also the collective knowledge of her cycles and moods going back generations. To live in community with a place creates a sense of collective coherence, to use Hübl’s term. The absence of it: trauma.

How do we begin to heal the wounds we’ve suffered from the loss of our planet’s most sacred places and our connection to them?

We use words to recreate whatever wild, beguiling music we’ve heard while surrendering ourselves to the landscape, in the hope others might be moved.

We overcome it in the same way we heal the grief of losing loved ones—we memorialize them and tell stories using their voices. But to do that, we must first remember how to hear their voices and recreate their sound.

In the 1909 YA novel A Girl of the Limberlost by Gene Stratton-Porter, the main character, Elnora, sought refuge in the swamp to escape the hardships in her home. The swamp soothed her as a mother might, with its cool shade and lilting lullaby. Elnora, eventually found an old violin hidden there, and she learned to play it by mimicking the sounds of the Limberlost.

As a young woman, Elnora moved to the city to try and save the swamp that was being gutted and carried away by developers. She played her violin for an audience of urbanites, sharing the music of the Limberlost with them. They were transported, hearing the swaying of the beech trees, and the voices of the maples, walnuts and cherry trees that were being destroyed. The city people who’d never been to the Limberlost, were so moved by Elnora’s recreation of its voice, they provided the remaining swamp with protection, so that they might one day hear the wild music themselves.

For nature writers, it is the same. We use words to recreate whatever wild, beguiling music we’ve heard while surrendering ourselves to the landscape, in the hope others might be moved enough to love it and protect it.

Humans suffer from the lie of disconnection, believing that we are separate from nature and each other. We pretend that connection comes from a network of followers or checking off lifelong bucket lists. But these only serve as a distraction from the grief we feel at losing our planet and our deep connection to each other. How do we, as Joni Mitchell wrote, get ourselves back to the garden, especially when the song is tragic and painful?

We remind ourselves that space and Spirit are connected and surrender to the consciousness of place. We share it collectively, and when the grief that comes with loss appears, we remember that ospreys choose trees that have died to build their nests, and lodgepole pine forests must burn in order to regenerate.

__________________________________

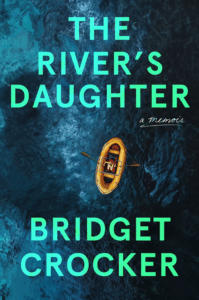

The River’s Daughter by Bridget Crocker is available from Spiegel & Grau.

Bridget Crocker

Bridget Crocker is a trailblazer in women’s empowerment within the outdoor industry. A leading whitewater rafting guide, she has led remote river expeditions down many of the world’s greatest river canyons in far-flung regions of Zambia, Ethiopia, the Philippines, Peru, Chile, Costa Rica, India, and the Western United States. She is a contributing author to Lonely Planet guidebooks and its Travel Anthology and to The Best Women’s Travel Writing series from Travelers’ Tales, and her work has been featured in magazines including Westways, Men’s Journal, National Geographic Adventure, Trail Runner, Paddler, Outside, Vela, and Patagonia’s blog, The Cleanest Line, among others.