Writing in the Shadow of a Masterpiece: On Homage

Margot Livesy Celebrates the Joy and Anxiety of Literary Borrowing

“Neither a borrower nor a lender be;

For loan oft loses both itself and friend,

And borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.

–Polonius, Hamlet

Ezra Pound’s “make it new” is one of the most famous commandments of 20th-century art and, like much great advice, is more complicated than it at first seems. When I began to write, I interpreted him to be urging originality. A story was not worth writing if it didn’t have a fresh and surprising plot; I had not yet discovered the possibilities of prose. If I had looked at Pound’s own work, full of translations and reworkings, I would have realized that the “it” in “make it new” is not so much the “world” as “art” and that Pound is saying much the same thing as James Baldwin at the end of his story “Sonny’s Blues.” Baldwin’s narrator is in a bar listening to his brother, Sonny, play the piano with a group of musicians, led by Creole:

Creole began to tell us what the blues are all about. They were not about anything very new. He and his boys up there were keeping it new, at the risk of ruin, destruction, madness, and death, in order to find new ways to make us listen. For, while the tale of how we suffer, and how we are delighted, and how we may triumph is never new, it always must be heard. There isn’t any other tale to tell, it’s the only light we’ve got in all this darkness.

Let me suggest, then, that one way to make both art and the world new, a way that would never have occurred to my younger self, is to consciously retell an old story.

Such retellings are referred to in various ways. Sometimes they are called “borrowing,” or “reimagining,” or “quoting.” Sometimes they are called “homage,” that elegant French term that points to the superiority of the original. The French critic Derrida, punning on ontology, uses the term “haunting.” I love this image of the earlier work ghosting around in the background of the new. When done secretly, with intent to deceive, it is described in harsher terms as copying, or plagiarism, or theft. This kind of close borrowing has been with us for centuries, perhaps as long as people have been making art. Did the first cave painters copy each other’s bison and horses?

*

There are several large categories of homage. First, the one we immediately recognize, is the faithful, foregrounded, unmistakable homage. One of the best-known contemporary examples is Jane Smiley’s novel A Thousand Acres, in which almost every scene of King Lear is transposed to a farm in 1970s Iowa. From the opening pages, when Larry Cook decides to divide his land among his three daughters, we are aware of the novel’s ambition. As we read further, it becomes apparent that Smiley is not merely nodding toward her original, or using it as a starting point, but following the plot in almost every detail. For many readers a significant part of the suspense of A Thousand Acres comes from wondering how she will re-create, or navigate, Shakespeare’s great moments—Gloucester’s blinding, for instance, or the storm scene—in the Iowa countryside.

A much earlier version of the faithful homage can be seen in Sir Walter Raleigh’s poem “The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd.” Writing in 1600, Raleigh is responding to Christopher Marlowe’s poem of the previous year: “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love.” Marlowe’s shepherd offers his beloved the conventional pleasures:

And we will sit upon the Rocks,

Seeing the Shepherds feed their flocks,

By shallow Rivers to whose falls

Melodious birds sing Madrigals.

And I will make thee beds of Roses

And a thousand fragrant posies,

A cap of flowers, and a kirtle

Embroidered all with leaves of Myrtle;

The shepherd continues to propose his list of gifts and enchantments without irony, in fiercely end-stopped iambic pentameter, and ends on exactly the same note as he began:

The Shepherds’ Swains shall dance and sing

For thy delight each May-morning:

If these delights thy mind may move,

Then live with me, and be my love.

Raleigh’s nymph, however, is not fooled for a second. Her poem opens with a syllogism:

If all the world and love were young,

And truth in every Shepherd’s tongue,

These pretty pleasures might me move,

To live with thee, and be thy love.

But, alas, this antecedent is manifestly false. The world is neither young nor truthful, and the nymph goes on to dismiss the shepherd’s blandishments not calmly or humorously, but savagely—“Time drives the flocks from field to fold, / When Rivers rage and Rocks grow cold, / And Philomel becometh dumb”—until her last irrefutable quatrain:

But could youth last, and love still breed,

Had joys no date, nor age no need,

Then these delights my mind might move

To live with thee, and be thy love.

Just for a moment Raleigh allows us to glimpse that, even while he mocks and destroys Marlowe’s idyll, he wishes the world were more like the shepherd’s than the nymph’s. His poem is overt in its argument and it demonstrates one of the truths of homage: namely that writing back, even when done as faithfully as in A Thousand Acres, nearly always involves a critique of the original, or at least casts it in a new light. It is not possible to explore how every art form borrows and quotes, but looking at visual art we find many examples of homage, from the faithful to the subversive. Among the more faithful, I would suggest, is Manet’s Olympia, which pays homage to Titian’s Venus of Urbino. More than 300 years later, Manet makes us look at Titian’s masterpiece in a new way.

Venus of Urbino (Titian) and Olympia (Manet)

Venus of Urbino (Titian) and Olympia (Manet)

Faithful borrowing, however, is not always immediately obvious. In The Story of Edgar Sawtelle, David Wroblewski also turns to Shakespeare but does so in a much more covert fashion than Smiley. The novel is set in a dog kennel in northern Wisconsin, and most readers only slowly become aware that the account of Edgar’s family, and the famous Sawtelle dogs they breed, is a reenactment of Hamlet. Edgar’s favorite dog, the amazing Almondine, plays the part of Ophelia, and suffers a similar fate. Other characters and events map onto the play with similarly tragic results. This kind of gradual revelation demands more space than a poem, or even a long story, can provide.

A second category of homage is the much less faithful, slantways retelling that still makes clear the borrowing and still, despite departures from the original, follows the same arc. We begin and end in roughly the same place but for many pages we are mostly oblivious to the original. In her novel Foreign Bodies, Cynthia Ozick pays lively tribute to Henry James’s The Ambassadors. Her heroine—the clever, courageous Bea Nightingale—steps with aplomb into Lambert Strether’s shoes as she takes to the streets of Paris in an attempt to rescue her nephew. Similarly, in “Gold Boy, Emerald Girl” Yiyun Li transposes William Trevor’s “Three People” from Ireland to Beijing. In Trevor’s story an elderly man, living alone with his surviving daughter, hopes that the young man who visits the house to do odd jobs will marry her. In Li’s story a mother urges her son, a gay man in his forties, to marry one of her former students. The secrets in the two stories are very different but the arc and the somber tone are similar. Li, like Trevor, allows us to understand all three points of view. Patricia Park, in her novel Re Jane, also works a clever transposition. She sets her version of Jane Eyre mostly in a Korean American community in New York and lets the reader figure out for herself that the feminist literary critic, writing away at the top of the house, is a version of Mrs. Rochester.

We can see this kind of relationship at work in another pair of poems: Sir Philip Sidney’s sonnet “With how sad steps” from Astrophil and Stella and Philip Larkin’s “Sad Steps.”

With how sad steps, O moon, thou climb’st the skies!

How silently, and with how wan a face!

What! May it be that even in heavenly place

That busy archer his sharp arrows tries?

Sure, if that long-with-love-acquainted eyes

Can judge of love, thou feel’st a lover’s case:

I read it in thy looks: thy languished grace

To me, that feels the like, thy state decries.

Then, even of fellowship, O Moon, tell me,

Is constant love deemed there but want of wit?

Are beauties there as proud as here they be?

Do they above love to be loved, and yet

Those lovers scorn whom that love doth possess?

Do they call ‘virtue’ there—ungratefulness?

Several centuries later Larkin signals with his title “Sad Steps” that he is writing back to Sidney, but then uses the vernacular of his opening line—“Groping back to bed after a piss”—to make us forget. The poem describes the speaker parting the curtains and being startled to discover “the moon’s cleanliness.” He goes on to make fun, in increasingly high diction, of the ways in which poets have addressed the moon: “Lozenge of love! Medallion of art!” But then he too, in the last stanza, succumbs to the moon’s power: it is, he tells us “a reminder of the strength and pain / Of being young: that it can’t come again, / But is for others undiminished somewhere.”

Larkin, like Sidney, has reached a position of high melancholy on the subject of romantic love, although his stance is one of a noncombatant, looking back from middle age, whereas Sidney is still in the thick of battle. The “undiminished” of Larkin’s last line gracefully echoes Sidney’s “ungratefulness.” Like Raleigh’s poem to Marlowe, Larkin’s poem is both homage and reply but it is also very much its own work of art, one that can be appreciated by readers with no inkling of its ancestor.

A third category of homage is the retelling from a different point of view. This is almost invariably subversive and has grown increasingly popular in the last half century. Tom Stoppard’s 1966 play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, which puts the two minor messengers in Hamlet center stage, is one of the best-known examples. Stoppard makes riotous fun of the messengers, and of the canonical play, while also showing us their deaths, which Hamlet barely mentions.

Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea was published the same year and has a darker purpose. The novel is mostly a prequel to Jane Eyre told partly from the point of view of the young Mrs. Rochester and partly from the point of view of Rochester himself. Writing in the first person, Rhys finds a sympathy for each character that is lacking in the original. Not long after Jane Eyre was published, Charlotte Brontë expressed regret for her depiction of Bertha Rochester; we should pity the mad, she claimed, not demonize them. Rhys follows this advice. She renames Bertha “Antoinette” and gives her a complicated history, making her an outcast twice over—in her family, and in the Caribbean society that labels her “a white cockroach.” As for Rochester, he becomes the beleaguered younger son, coerced into marrying for money. The novel was embraced not only as literary homage but also as a piercing story of the corrupt power of colonial England.

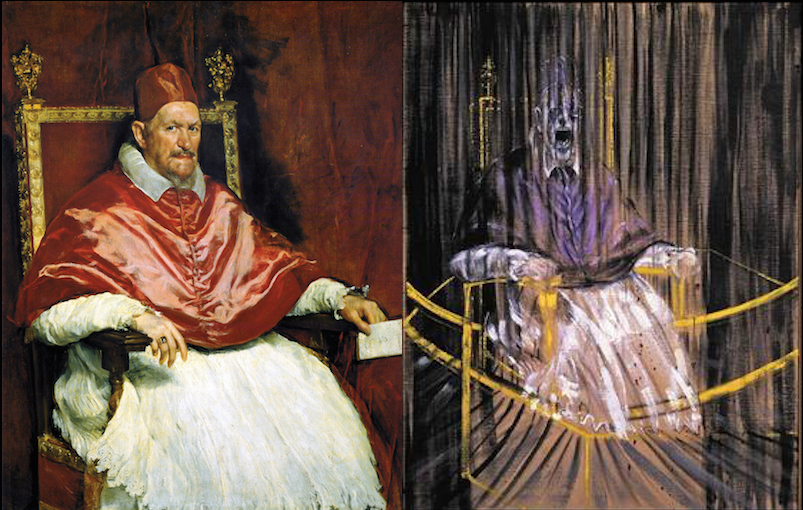

In visual art we see the same kind of relationship between the Spanish painter Velázquez’s portrait of Pope Innocent X, painted around 1650, and the British painter Francis Bacon’s series of screaming popes, painted in the 1950s. Bacon repeatedly questions, mocks, sabotages, and denounces the power and privilege of the original.

Portrait of Pope Innocent X (Velásquez) and Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, Francis Bacon

Portrait of Pope Innocent X (Velásquez) and Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, Francis Bacon

There are also more playful kinds of homage, which both acknowledge the original and depart radically from it. Julian Barnes’s Flaubert’s Parrot does not aspire to retell Flaubert’s A Simple Heart but offers a witty exploration of that novella as well as of Madame Bovary and of Flaubert’s life. In a somewhat similar fashion Michael Cunningham’s The Hours both follows the plot of Mrs Dalloway and draws on the life of Virginia Woolf.

The last category of homage I want to mention comes from the eloquent literary and cultural critic Roberto Calasso. According to Calasso, James Joyce’s Ulysses is not a retelling of The Odyssey so much as a reimagining of the myth of Odysseus, which has no single author and has been repeated over the centuries in various forms. Myths, legends, and fairy tales, he suggests, are owned in common and are available to everyone. Calasso also cites some singly authored works that have achieved this mythic status. Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, for example, has been retold or subverted by Elizabeth Bishop, Derek Walcott, Michel Tournier, and J. M. Coetzee, among others. These reimaginings simultaneously call the original into question and reflect its status in the culture.

Looking at these examples of homage, a couple of criteria immediately become apparent. The earlier work is usually well known, if not canonical, and the borrowing is not a secret, guilty or otherwise. In his 2007 essay “The Ecstasy of Influence,” the novelist Jonathan Lethem describes a story published in Germany in 1916. It follows a cultivated middle-aged man who, while traveling, rents a room and proceeds to fall in love with his landlord’s daughter. Despite her age—she is not yet thirteen—the relationship is consummated. Then the girl dies, and the man is left alone forever. The title of this eponymous story is “Lolita.” Lethem speculates as to whether Nabokov’s borrowing was conscious. Certainly his use of the name suggests that he was not trying to hide his debts. Still this does not, for me, count as homage. Nabokov did not expect his poorly educated American readers to know a story published in Europe forty years earlier; he was not relying on that tension between his work and the original. And of course what is most essential in Lolita, the gorgeous, driving voice—“light of my life, fire of my loins”—is entirely his own.

Looking at any longer list of retellings also makes clear that Shakespeare is a special case of a single author whose work has become mythic. He himself famously borrowed many of his plots, and it seems only fair that his work is so widely the subject of homage that a whole industry has sprung up around these forays into intertextuality. This torrent of borrowings also means that, when appropriating Shakespeare, an author faces the additional burden of being compared not only with the original but also with the works of fellow borrowers.

Which brings me to my own large, vested interest in this topic. Ten years ago, if I had been asked to expound on homage I would have done so with enthusiasm but with no particular axe to grind. I had secretly borrowed (or do I mean “appropriated”?) an image from the Scottish writer Lewis Grassic Gibbon here, an emotional transaction from Henry James there, but I had never attempted full-scale homage, and, while enjoying the reimaginings of other authors, I had no plans to enter such complicated territory. But in 2008 I began to write a reimagining of a novel that has never been out of print since it was first published in 1847, and which, as I’ve mentioned, was already the source for Rhys’s iconic homage: Jane Eyre.

Writing a novel is hard enough. Why write in the shadow of a masterpiece? I cannot entirely trace the route by which my answer to this question changed from “Good point. I won’t” to “Because I must,” but I can name some significant stages on my journey. In my novel The House on Fortune Street one of my characters is doing his PhD on Keats. Rereading Keats’s poems and his passionate, lively letters was a delight, and I relished the challenge of trying to weave glimpses of the poet’s work and too-short life into my narrative. Once I finished this section of the novel I began to ponder whether I could do something similar for my three other main characters and give each of them what I decided to call a “literary godparent,” an author whose work and life addresses their deeper preoccupations.

This was my first venture into thinking as a writer—rather than as a reader, or a critic, or a teacher—about literary borrowing and what it could do for my fiction. I had two rules for my godparents. They would be well-known 19th-century British writers, and almost everything the reader needs to know about them, and the text being referenced, would be in the narrative. While I enjoyed working on this aspect of the novel, I did not finish Fortune Street thinking, now I want to attempt a full-scale homage of one of my favorite novels.

I first read Jane Eyre the summer I was nine years old and living in the grounds of the boys’ private school in Scotland where my father taught. I chose the novel from his bookshelves because it had a girl’s name on the spine, and when I opened it—good news!—it turned out to be about a girl almost my age. As I kept reading, I found several more reasons to identify with Jane. The Scottish moors were surely not so different from the Yorkshire moors, and the school where my father taught—it was founded the same year that Jane Eyre was published—was a Gothic building with battlements and attics, an excellent stand-in for Thornfield Hall. Closer to home, my severe stepmother bore a strong resemblance to Jane’s aunt. Soon after I read the novel I gained an additional reason for empathizing with Jane when we moved to the south of Scotland and I too was sent to a dreadful girls’ school.

Since that first passionate reading, I have reread the novel a number of times, for pleasure and to teach. Certain events in Jane’s life are more real than events in my own. Soon after I published Fortune Street, I once again reread Jane Eyre in order to meet with a book club in Boston. The room that night was full of passionate readers, and here was the thing that struck me: although no one admitted to having a difficult stepmother, or growing up in the shadow of a Gothic boys’ school, or attending a dreadful girls’ school, everyone had entered into Jane’s story. And everyone seemed to understand, however inchoately, that the reason Jane cannot marry Rochester the first time is not only because Mrs. Rochester’s brother interrupts the ceremony. Jane cannot marry Rochester because she is not yet her own person.

Brontë herself may not have understood what she accomplished when a voice calls out in the church, “The marriage cannot go on: I declare the existence of an impediment.” In writing this dramatic scene she satisfies the conventions of both the heroic novel, by which the heroine must face repeated trials, and the gothic novel, which demands dark coincidences. She also achieves a crucial deepening of her psychological themes.

As I drove home from the book club, I realized I had made a typical reader’s mistake in thinking that the novel spoke to me because of the superficial similarities between my life and Jane’s. That roomful of readers made clear that the real reason why the novel endures has much more to do with Brontë’s skillful decisions. The year before she wrote Jane Eyre, she had written a novel titled The Professor, which drew on similar material: a romance between an older, more powerful man and a young woman, told in the first person from the point of view of the man. The novel was intended, along with Emily’s Wuthering Heights and Anne’s Agnes Grey, to be part of a triple-decker, a popular form of Victorian publishing. But while her sisters’ novels were promptly accepted, The Professor was roundly rejected. Brontë began Jane Eyre in response to the nicest of the rejections, and first and foremost among her good decisions was to make her narrator a young woman not so different from herself, capable of remarkable passion and poetry. She wrote the opening pages while nursing her father through cataract surgery, an experience that may have led to her decision to blind Rochester later in the novel.

Several other critical choices contribute to the novel’s enduring appeal. It is structured as a journey with five distinct settings, each with its own atmosphere and psychological arc. And Brontë makes Jane—small, plain Jane—the embodiment of two of our great archetypes: the pilgrim and the orphan. In his essay “Family Romances” Freud argues that children take refuge in the belief that they are orphans because on the one hand they feel slighted and on the other they begin to notice that their parents are less than perfect. These difficult people, the child thinks, are not my parents; my real parents are wonderful, talented aristocrats. Whatever the truth of Freud’s theory—I never doubted that my difficult parents were mine—readers love orphans. Victorian literature is awash with them, and more recently Harry Potter and The Goldfinch prove that they still cast a powerful spell. The orphan’s story, without parents to limit the imagination or provide a safety net, is all our stories writ large.

*

Shortly after that evening at the book club, I hid my copy of Jane Eyre and sat down to ask again Brontë’s great question: How is a girl with no particular talents, no means, and no family (that she knows of) to make her way in the world? Gemma Hardy, I decided, would be an orphan growing up in 1960s Scotland. I knew, almost from the first page, that I was not going to follow Smiley in faithfully and obviously updating the story, or even Wroblewski in doing so faithfully and subtly. Indeed so much have social and sexual mores changed, along with our attitudes to mental illness, that I am not sure such an enterprise is possible. I did briefly consider reversing Rochester’s and Jane’s roles, making them a young man and an older, more powerful woman, but (sadly) I worried about issues of plausibility.

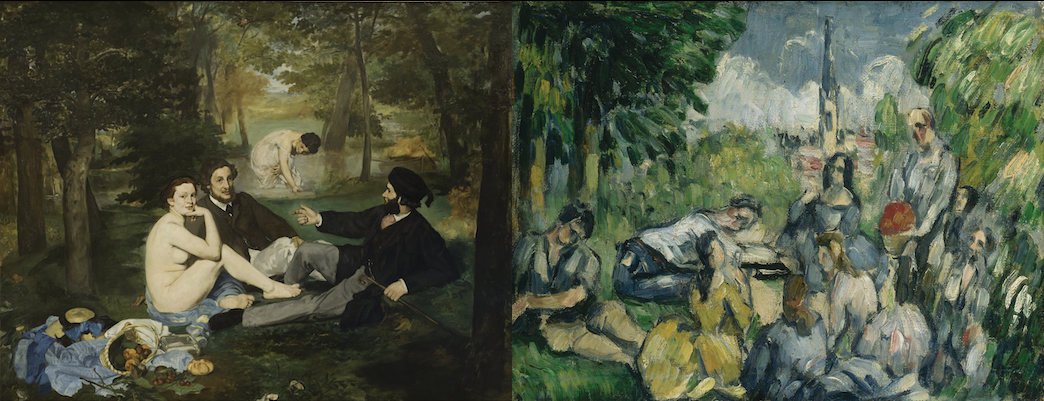

My hope was to be both faithful and faithless, somewhere between, say, Ozick and Smiley. I wanted Gemma to have her own story, even while she, in many respects, follows Jane’s. To readers who know Brontë’s work, I signaled my intentions by modeling my opening chapter on what I remembered of the beginning of Jane Eyre—the fight between Jane and her cousin and her banishment to the haunted red room. But in my second chapter, I departed radically from Brontë and gave Gemma an Icelandic childhood. If I had to choose a pair of paintings to illustrate my homage and its relationship to the original, it would perhaps be Manet’s iconic Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe and one of Cézanne’s several paintings by the same name.

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Manet) and Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Cezanne)

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Manet) and Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Cezanne)

Writing, for me, is always a roller coaster, and it was never more so than when working on Gemma Hardy. On good days I felt that I was standing on the shoulders of a giant, but on bad days all I could see was the giant looming over me. A major challenge of homage, I discovered, is how to avoid irritating readers who know the original while at the same time including those who don’t. My solution—still evolving—is a variation on reader response theory. Baldly summarized, reader response theory claims that readers complete the text in various ways and that that’s all right. (The classical view argues that there is a single text and a single, correct interpretation.)

Putting theory aside, I would say that the question of how to include readers who know the original and those who don’t is not so different from the question of how to include readers who know Poughkeepsie and those who don’t, those who are parents and those who aren’t, those who love horses and those who can’t tell a hoof from a fetlock. Since the Second World War readers have been growing increasingly diverse; no writer now, in Europe or the States, can count on having a single unified audience. In a workshop I taught in Miami a few years ago I had 20 students from 11 different countries. We debated the meaning of such words as “home,” “family,” “love,” “goodness.”

In an effort to include as many readers as possible, let me summarize the plot of Jane Eyre: A ten-year-old girl, an orphan, is sent by her cruel aunt to a dreadful girls’ school where she is hungry and cold and her best friend dies. Jane survives, and, at the age of 18, finds a job as a governess at Thornfield Hall. There she falls in love with her employer, the much older Mr. Rochester, and he with her. But on their wedding day Jane learns that there is already a Mrs. Rochester, a madwoman who is kept prisoner in the attic. She flees Thornfield Hall and after wandering for several days collapses, starving and penniless, on the doorstep of some kind people. She recovers, becomes the village schoolteacher, and narrowly escapes marriage with a man who does not love her. The novel ends in sweeping romantic fashion. Jane gains a family (the kind people turn out to be her cousins), money (a long-lost uncle dies), and the husband of her heart’s desire: Rochester, now blind.

In its own small way, not remotely comparable to neurosurgery or NASCAR racing, making art is a risky business. In retelling a classic one faces not only the usual risks but also the particular challenge of how to negotiate the climactic scenes of the original: How can one hope to do them better? Or even half as well? Yet it seems impossible to write a reimagining without attempting a reprise of at least some of the key scenes. Others, however, are best subverted or ignored. Fairly early in my novel I recognized that re-creating Mrs. Rochester in 1960s Scotland was, for me, an impossible task. There would be no attics in Gemma Hardy.

Some elements of the original, however, were too central to ignore. What would be the point of writing even a heavily camouflaged, or indirect, reimagining of Jane Eyre without a Rochester-like figure? If I wasn’t going to depict a version of that central relationship, then I might as well exorcise Brontë’s ghost and chart my own course. Every artist who attempts an homage has to find her or his own way to answer a version of these questions.

It was only when I was well into writing the novel that another truth also became apparent. Homage brings one up against not only the strengths of the original but also the shortcomings. Most readers remember the same dramatic episodes in Jane Eyre: the terrible school, the first meeting, the mad wife, the interrupted marriage, and the final reconciliation. All except the last take place in the first two parts of the novel. The third part, which shows Jane wandering on the moors, being rescued, fending off her suitor and his tedious religiosity, has its longueurs. What is the reimaginer to do? I won’t describe my attempts to answer this question, only point out that both the best and the worst parts of the original are problematic. Almost inevitably one is going to fall short of the former and one follows the latter too closely at one’s peril.

Most writers also have to find a way to respond to the voice of their chosen text. Oddly, but perhaps understandably, writers who pay homage to Shakespeare seem to largely ignore this issue. But in The Hours Cunningham is clearly aware of Woolf’s cadences. And in “Gold Boy, Emerald Girl” Li pays homage to Trevor not just in her plot but in her prose. In Gemma Hardy I tried to find a voice that is simultaneously of its time and place, and yet hovers slightly above that time and place. Then there was the additional challenge of the soaring language Jane uses in her great speeches to Rochester. Here is her response when he pretends that he’s going to marry another woman and asks Jane to remain in his household:

“I tell you I must go!” I retorted, roused to something like passion. “Do you think I can stay to become nothing to you? Do you think I am an automaton?—a machine without feelings? And can bear to have my morsel of bread snatched from my lips, and my drop of living water snatched from my cup? Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless?—You think wrong!—I have as much soul as you,—and full as much heart! And if God had gifted me with some beauty, and much wealth, I should have made it as hard for you to leave me, as it is now for me to leave you.

To describe Jane’s outburst as “something like passion” is a woeful understatement. Her poetry conquers both Mr. Rochester and the reader. No wonder we don’t stop to question the plausibility of a wealthy, powerful, upper-class man falling in love with a poor, plain, middle-class woman. And no wonder that to write my reimagining I had to hide the original. Once I had begun Gemma Hardy, I did not open my copy of Jane Eyre for three years.

So once again I have to ask: Why embark on such a hazardous enterprise? I put this question to the painter Gerry Bergstein, whose painting adorns the cover of this book and whose beautiful, witty work often draws heavily on art history. He came up with eight answers:

1. To provide a contemporary update of older themes that often contradicts the original

2. Sheer love

3. To make a cultural critique

4. To demonstrate political, or other forms, of social evolution

5. To distill the earlier work

6. To develop the traditions of a beloved forebear

7. Any combination of the above

8. As a joke

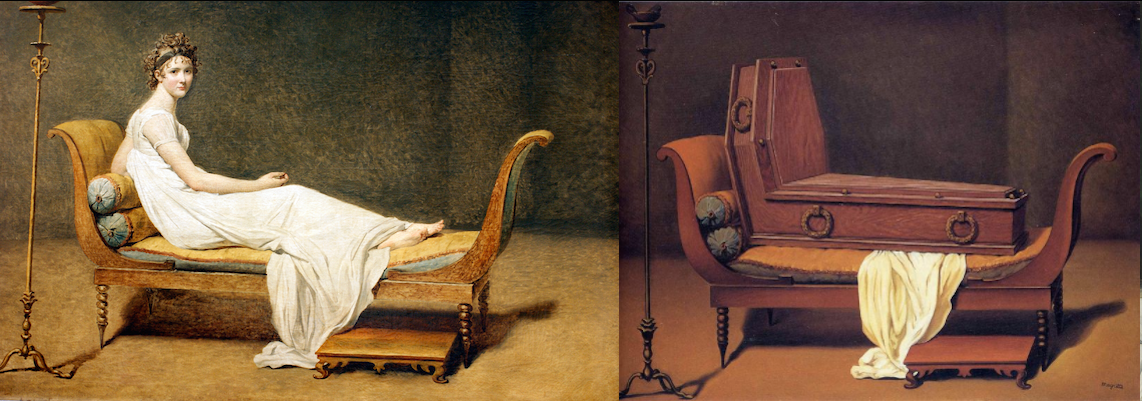

When I questioned this last point, Bergstein showed me René Magritte’s painting titled Perspective: Madame Récamier by David, in which the woman Jacques-Louis David portrayed in 1800 has been replaced by a coffin. Only the fall of white drapery suggests her presence.

Portrait of Madame Récamier (David) next to Perspective: Madame Récamier by David (Magritte)

Portrait of Madame Récamier (David) next to Perspective: Madame Récamier by David (Magritte)

I do think that #1, #2, #4, and #6 each played some part in my motivation. The idea of reexamining the possibilities for women’s lives more than a century after Brontë wrote was one of several reasons why I set the novel in the 1960s, shortly before that great wave of feminism broke over both Europe and the States. At that time in Scotland there were four professions open to middle-class women—nurse, teacher, secretary, wife—two more than were open to Brontë and her sisters before they added “writer.” And when a woman became a wife, the best of the professions, she almost invariably gave up her job outside the home. In writing Gemma Hardy I wanted to question those narrow expectations, and I wanted the reader to know that Gemma was growing up into a time of many more possibilities for women.

Most of Bergstein’s reasons suggest that the artist writing back does so out of the loftiest of motives, but perhaps, for some borrowers, there is a less lofty side. One of the challenges I regularly face as a novelist is hearing a great story that, even as I reach for my notebook, I realize I can tell only at the risk of losing family, friends, or employment. Jane Eyre is a fantastic story: my adopted father, reading it for the first time, missed a landing strip during World War II because Rochester was about to propose. Of course the writer in me longed to steal it. Happily, I discovered that in homage outright theft is impossible. My debt to Brontë is unmistakable.

One other ambition accompanied me throughout my writing of the novel. I wanted Gemma to be not just a character but a heroine. Although small in stature and young in years, I wanted her to be larger than life. To that end I made her face dragons and demons and disasters. And, like Jane, she is truthful and opinionated. A heroine cannot simply sit at home, drinking cups of tea.

Finally, and I’ve thought about this long and hard, there is the question of suspense in literary homage. A few years ago in London I took an elderly friend to Oedipus Rex. Philip had accepted my invitation eagerly and as the lights went down he leaned forward. Gradually, as he whispered—“But that’s his mother!” “Don’t do it!”—I realized he did not know the plot. He was on the edge of his seat about what was going to happen; I was on the edge of mine about how it was going to happen, and why. In the reimagined work the suspense for one group of readers comes partly from their very familiarity with the plot and the characters; for another it resides purely in the work itself, which is why the reimagining needs to be its own compelling story. The good news is that we value both kinds of suspense. Indeed some people would argue that the pleasure of revisiting is superior to that of the first encounter. When giving readings of her story “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” Flannery O’Connor always began by describing the plot in order to allow her listeners to pay attention to what really matters.

And that—what really matters—is surely the key to successful homage. As I hope I’ve made clear, I think Polonius is wrong, at least when it comes to art. We are not diminished or dulled by borrowing and lending. In the best homages the contemporary artist is able to plumb some aspect of her or his own deepest interests, to reach what really matters, while simultaneously agreeing with or repudiating, delighting in or detonating, the original work. I have come a long way from that house beside the Scottish moors where I first read Jane Eyre to the desk in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where I now write. On my journey I have paid homage to several writers—they had no say in the way I borrowed their landscapes and their insights, their nightingales and their bad behavior. I hope in doing so to have brought attention to their work and, at the same time, I hope to have made something new.

__________________________________

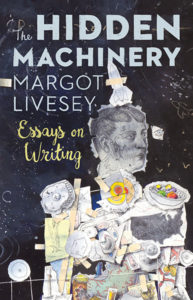

From The Hidden Machinery: Essays on Writing. Used with permission of Tin House. Copyright © 2017 by Margot Livesey.