In recent years I have benefited from leading a carefully unified life, writing fiction and nonfiction in a similar style, speaking privately and publicly in a single voice, and doing the same thing at the same time day after day. Living alone in rural seclusion, with minimal peripheral interference, financially secure at eighty years old, I have been gifted the time to concentrate on the publication, since 2019, of four novels and three art historical catalogues, for the British Museum, the Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett, and East Quay in Somerset.

Without the need or desire to compartmentalize my interests, the same subjects of long-term concern appear in my nonfiction and my novels, no special research required into creative areas attended to for decades. One of the literary cross-fertilizations involves artists’ cards, which feature in the novel Bolt from the Blue (2021), composed in the form of correspondence by letter, postcard and email between a single mother in Birmingham and her artist daughter in London.

In the study of art works as in the writing of fiction, I am drawn to neglected subjects.

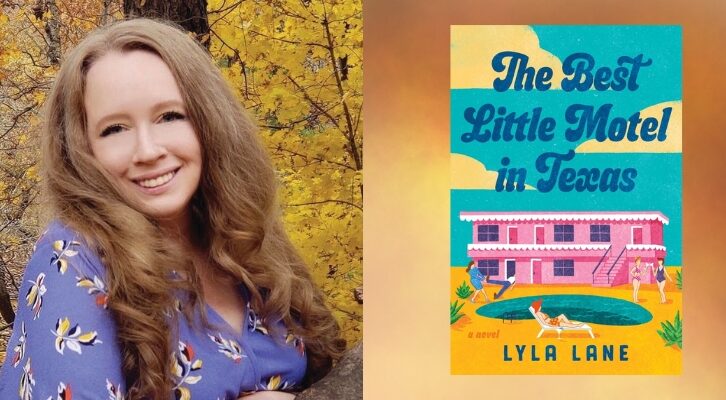

The text included comment on the postcards sent and received, including: “On a postcard with red letters on yellow ground, the word Library mutating into Liberty, published by Sheffield Library. Mum must have been up there sometime. She never told me.” This anti-cuts postcard is now in the collection of Cambridge University Library, included in my gift of several hundred British political cards from the 1960s onwards.

Postcard for campaign of the 1990s by the Central Library, Sheffield. Courtesy Jeremy Cooper.

Postcard for campaign of the 1990s by the Central Library, Sheffield. Courtesy Jeremy Cooper.

The novel also refers to American artists’ cards, two-and-a-half thousand of which I have given to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, including a rare portrait of Vito Acconci, a key figure in the avant garde performance scene in New York in the 1970s, as documented in detail in the collection. I transferred my admiration of the work of Acconci, Moorman, Jonas, Matta-Clark and other US artists of the period to Lynn, the principal character in Bolt from the Blue.

In the study of art works as in the writing of fiction, I am drawn to neglected subjects. The Director of the British Museum wrote in the foreword to my catalogue of their 2019 exhibition The World Exists to Be Put on a Postcard: “A carrier of an artist’s idea and practice and often politically subversive in nature, the postcard circumvented the gallery or museum system and circulated widely in the public domain… This book, and the accompanying exhibition, show just how witty, sharp and potent these objects can be.”

Similarly, I tend to explore in fiction areas of personal concern irregularly dealt with by other novelists, such as the first-person journal of suicidal breakdown in Ash before Oak (2019). My latest novel, Discord (2026), inhabits the world of contemporary classical music as seen from the alternating viewpoints of the two women protagonists, a young saxophonist and older composer.

As with other books, I write about the kind of things I have seen, heard and thought about over the years. Physical and emotional descriptions of musical performances which I attended are given to the novel’s fictional characters, ranging from Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time in the Wigmore Hall to Frédéric Acquaviva’s multimedia creation Antipodes at Café Oto in Dalston.

On a personal level, I seek also to secure a convincing interconnectedness between different areas of my own life.

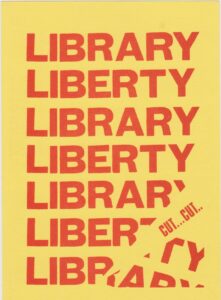

It was in The Folded Lie (1998) that I began to use the real names of places and people in my novels, instead of inventing a disguise. Some artist friends have appeared in different roles in two or three novels as well as in my non-fiction. Gavin Turk, for example, is not only in the fictional text of The Folded Lie but also allowed me to use his work Godot (1996) for the cover. My connection to this group of young artists was formed in the early 1990s when they were my neighbours in then semi-derelict Shoreditch, before making public names for themselves as the YBAs.

I subsequently wrote a non-fiction book about this time, titled no FuN without U: The art of Factual Nonsense (2000), following this with the survey Growing Up: The Young British Artists at 50 (2012)—both these books feature artists and ex-Shoreditch residents Gary Hume and Gavin Turk, as does Bolt from the Blue.

Gavin Turk’s cover of Jeremy Cooper novel The Folded Lie (1998). Courtesy Jeremy Cooper.

Gavin Turk’s cover of Jeremy Cooper novel The Folded Lie (1998). Courtesy Jeremy Cooper.

Two other important references in recent novels to my involvement with contemporary artists are Tracey Emin’s appearance in Bolt from the Blue and Jeremy Deller’s in Discord. I describe a visit to Emin’s six-month-long performance piece The Shop (1993) in Brick Lane—four years later she unexpectedly gifted me a monoprint portrait, a work which I have illustrated in several art books and am now giving to the British Museum.

The first of Deller’s works I saw was a performance of Acid Brass in 1997 with the Williams Fairey Colliery Brass Band playing his selection of acid house music. Drawings and artists’ cards by Deller gathered by me over the years are part of my gift to the British Museum, whilst in Discord I have invented a series of performances given by my fictional saxophonist Evie at the end of six different Victorian piers, described as choreographed and filmed by Deller for Channel 4. By writing in fiction both about events which actually took place and about living people doing invented things, my aim is to make the text ring true in the context of the novel. On a personal level, I seek also to secure a convincing interconnectedness between different areas of my own life.

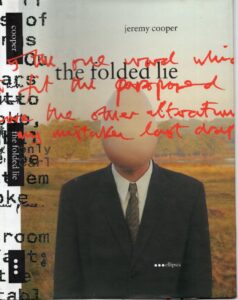

Mimesis, a self-published postcard of 1994 by Jeremy Deller, the photograph taken at Chessington World of Adventures of the artist kissing a large mural. This artists’ card was given by Jeremy Cooper to the British Museum and illustrated in their exhibition catalogue The World Exists to Be Put on a Postcard [2019]. Courtesy Jeremy Deller.

Mimesis, a self-published postcard of 1994 by Jeremy Deller, the photograph taken at Chessington World of Adventures of the artist kissing a large mural. This artists’ card was given by Jeremy Cooper to the British Museum and illustrated in their exhibition catalogue The World Exists to Be Put on a Postcard [2019]. Courtesy Jeremy Deller.

Exhibition Recollection (2025) at East Quay, Watchet, of art works belonging to Jeremy Cooper, with reader’s display of his publications. Courtesy East Quay.

Exhibition Recollection (2025) at East Quay, Watchet, of art works belonging to Jeremy Cooper, with reader’s display of his publications. Courtesy East Quay.

In an essay published to accompany the exhibition Recollection at East Quay, which featured several hundred works of art from my home, gallery director Jess Prendergrast described my approach to creativity as a “a process of making contacts and connections, which has added a richness both to his life and to the art canon at large. This reveals a story and history of creative and personal connections between often now-famous artists, before they were so, which would have otherwise gone unremarked and unremembered.”

It is true, I do enjoy the discovery of unexpected connections in various aspects of life. I was delighted to learn that the crusader tomb in the ancient church on the Cothelstone Estate in Somerset, across the fields from the rented cottage where I have lived since 2000, appeared in a telling episode of Evelyn Waugh’s semi-autobiographical novel The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold (1957). Waugh was based for many years in a grand house in nearby Combe Florey and adapted this local ecclesiastic landmark for fictional purposes.

An additional connection emerged when I was hospitalized in Taunton with severe depression, a louder echo of Waugh’s own bouts of despair as transferred to his alter ego Gilbert Pinfold. I too have openly used Cothelstone locations in published fiction. Linking past and present and making this available in the future through fiction is, I find, exhilarating.

View from Jeremy Cooper’s cottage in West Somerset. Courtesy Jeremy Cooper.

View from Jeremy Cooper’s cottage in West Somerset. Courtesy Jeremy Cooper.

__________________________________

Discord by Jeremy Cooper is available from Fitzcarraldo Editions.

Jeremy Cooper

Jeremy Cooper is a writer and art historian, author of six previous novels and several works of non-fiction, including the standard work on nineteenth century furniture, studies of young British artists in the 1990s, and, in 2019, the British Museum’s catalogue of artists’ postcards. Early on he appeared in the first twenty-four of BBC’s Antiques Roadshow and, in 2018, won the first Fitzcarraldo Editions Novel Prize for Ash before Oak. His latest novel, Discord, is published by Fitzcarraldo Editions in February (UK) and June (North America).