Writing Across Time and Queer Generations

Cooper Lee Bombardier in Conversation with Paul Lisicky

In a moment of ever-shifting histories, from pandemic to protest, authors Paul Lisicky (Later) and Cooper Lee Bombardier (Pass With Care) met in virtual conversation to talk about writing outside of definition, shifting dunes of form, a collapsing and accordioning of time, and allowing a subject to become fractal. Both writers connected over themes of sex, death, and survival in their work, and the impossibility of approaching certain subjects head-on. In a time of isolation and confusion, meeting in this conversation felt like a life-giving act of care and generosity across queer generations.

*

Paul Lisicky: One of the things I love about Pass With Care is its refusal to be one thing, to take on one form. It’s always morphing, breathing, making itself up over and over again. Within the opening pages there are combinations of lists, short narratives, short prose pieces that move and think like poems. The book’s throwing out signals right away. It’s telling the reader how it expects to be read. Does that strike you as true?

Cooper Lee Bombardier: Yes, it is absolutely true. This book was in some ways an experiment in looking at similar transformative life events through different lenses of time and form. I wanted to see what the same event or moment might reveal when approached from a different vantage point or through a different configuration of language and shape. The earlier, older pieces in the book manifested from a self-taught, performative utility, a need to create a clearing to simply stand in. Then later, as I learned more through writing and reading, I understood that the same narratives could be manipulated differently, and something more interesting could be revealed by not looking head-on at a subject.

I saw something similar and really interesting at work in your book Later, in terms of form and chronology, and resisting confinement to genre. You start and end with the movement of the dunes and it shows how this is a place that will never be pinned down by any one person. You liken it to the idea of trying to look at God straight on. The idea of all of these artists over time try to capture and name the essence of an ever-shifting location like Provincetown, but the closer one looks at the place the more fractal it becomes.

You created this amazing interior voice. The narrator, the you of back then, has this curiosity of self and other, and there’s also this seamlessness between the wiser, older self, looking back at the experiences of this younger self, and one of the ways it seems you accomplish this is through the ability of the narrator to ask questions. The questions in memoir feel more valuable to me than texts that try to drive toward the answers. It doesn’t need to be nailed down for the reader in Later, and to nail down is futile, anyway, in a place that shifts due to sand, wind, sea, death, and the currents of people who come to claim the place. Will you talk a little bit about how you went about structuring this voice?

PL: The original draft was straightforward. I was excited that it seemed to have a linear, propulsive quality that I never thought I had the chops for. Most of my other work is so lateral or associative—it’s the prose work of a writer who primarily knows himself as a poet or musician. I’m not terribly drawn to straight-throughness, or the old presumption that duration equals depth. I like interruption, disjunction, key changes, meter changes.

“Writing, painting, sculpture—any kind of art making was involved in thinking about limits too, defying the shutdown of the body.”

It wasn’t long before I felt dissatisfied. Or maybe I felt the project lost some steam, or I was in argument with the whole idea of steam. I came back to it after The Narrow Door came out. I was spending the entire summer in Provincetown, and living there day in and day out, as I once did for many years reminded me that this wasn’t a place of a single shared narrative. Everyone who loves Provincetown brings their own myth to it. As a writer it’s impossible to colonize that place. Do so, and you’ll be corrected—you have to make space for other stories. All of that informed the tense of the book. Somewhere Bob Dylan says of Blood on the Tracks, “I wanted the past, present, and future all in the same room.” I knew I needed to suggest that somehow. I couldn’t live with myself if the book were simply this faux naif tale of a young man’s journey from innocence to experience. Instead, innocence and experience live right on top of each other throughout. And I tried to give the reader enough tools to make sense of all that from the get-go. As to how the book manages it on the craft level? No system: It relies on intuition sentence by sentence. I read it aloud, sometimes as I was writing. My voice box let me know if something felt off, pushed.

One thing I love about your own work is the sense that you read work in multiple genres. And that flexibility, that hunger and generosity shows up on every page. Which writers have been important to you, and how do you think their influence shows up in your work?

CLB: I’m a promiscuous reader. I read tons of creative nonfiction, and also scholarly work, science stuff, fiction, poetry, and though I don’t tend toward genre fiction usually, I’ve been making a point lately to read more of it, including YA, because authors writing in YA are really pushing forward an inclusivity and expansiveness for all kinds of characters and bodies on the page that seems way ahead of the pokey pace of literary publishing. And YA has a huge readership, so it seemed interesting to find out why, empirically. I’ve been working a lot more poetry into my reading diet.

I have many literary “mothers,” as my friend Sophia Shalmiyev would say. Some of the most important to me have been David Wojnarowicz, James Baldwin, Dorothy Allison, Lydia Yuknavitch, and Sarah Schulman. All of them come to mind when I am on the verge of backing away from something that terrifies me to write. I remember how much it changed my ability to live to read their work and think about what would’ve happened if they’d chickened out. So, I try not to chicken out. Lydia’s The Chronology of Water really helped me see memoir as capable of taking on many forms, and the idea that questions are perhaps more important than the tidy conclusions one tries to make in memoir. I appreciate what you say about generosity, because I am writing in conversation, at least in my own mind, with other authors much of the time.

The structure of Later reminds me of the project at the heart of Montaigne’s essais: his attempts—writing to discover or uncover, to find out what one knows. I sensed that openness in your writing; to me it echoed the encounters beneath the docks, a sense of being present to a moment and being open to whatever unfolded from it. Did you write with this sense of experimentation and discovery? Some sections cover a few pages while others are just glimpses. A lot can be seen through those glimpses. Following what you said above, did intuition also guide the length of each section? There is a quiet chronological drive to the book, but there is also this urgency: death is coming, is always coming, and the openness and exploration also feels metered by this impending sense of mortality. How did you find balance in the work between this sense of coming into one’s own creatively and sexually with the constant presence of death?

PL: I sensed early on that I wouldn’t be satisfied to simply reproduce what I already knew. I wanted the book to be more than an act of recovery. There’s nothing wrong with an act of recovery, a historical record, but it wasn’t enough for me. The book needed to be conscious of the possibility of inquiry, interrogation. Otherwise, I would have lost interest after a couple of chapters. I needed to lean toward the unexpected to keep it alive. I wanted to write something that taught me something. What was it like to live against anxiety and uncertainty? The book needed to have an independent mind. If the book was thinking, I’d learn something too. And maybe the reader.

As soon as I felt the book falling into comfortable patterns and a consistent tone, I made sure to disrupt it, and that probably accounts for the glimpses you mention. A glimpse gives the reader some space to bring their own imagination to the page. It gives them a little bit of freedom, even agency. I didn’t want to over-control the reader’s experience. Maybe it’s just that the nature of this material could be so intense that a consistent sense of density could overload. I wanted to give density to the real pressure points in the book, to those exchanges when the possibility of change was real.

My gut feeling is that death always saturates sex and art. Every attempt at physical connection, even if it’s casual, is freighted with the possibility of contagion, an ending. Writing, painting, sculpture—any kind of art making was involved in thinking about limits too, defying the shutdown of the body. The funny thing is that a few months back I read through the book in one of those moods, and thought, this is too ending-haunted? Did I overdo it? In some weird way I think our current moment is more attuned to what it means to be alive than those times that are overtly less tense, when we’re putting all of our energy into distracting ourselves from our mortality.

What other art forms feed your work? Have you ever been a musician or an actor or a painter, and if so, did you ever bring what you know from those fields into your writing?

CLB: My first creative love was visual art. This comes into my writing in terms of layering, image, texture, erasure. I haven’t made much visual work in the past couple of years because I’ve been really focused on writing. I went to art school right out of high school and was interested in experimentation: I’ve worked in photography, film, sculpture, performance, printmaking, and painting. I draw constantly. I wouldn’t describe myself as a musician, but when I was young, I played a couple of instruments, and in my 20s in San Francisco I sang in two bands. I love tactile skills, and I guess this is where my attention-deficit and curiosity collide with wanting to do things with my hands. I sew, work with wood, cook. I’m a generalist. I like figuring out a material process and seeing how I can develop or manipulate it. This totally translates into the writing process for me. I am most attracted to writing where the author has clearly lived, not just philosophizes about experience, but experience is not enough. That’s just the material that needs to be transformed, shaped, manipulated through process and craft.

What about you? Do you work in other forms or find your writing informed by other practices?

PL: I started playing the piano pretty early. First by ear, then I started taking lessons. By the time I started taking lessons I’d make up what I couldn’t sight read. My piano teacher would say, that sounds better than the original. I thought he was being too easy on me, but now I think he was doing this lovely thing: he was giving me permission. He was letting me know that music wasn’t just an act of obedience to some black mark over bars on the page. I got the sense that he believed that music was so much more than that, a complex language that had all sorts of hidden richnesses. And it controlled the performer as much as the performer tried to control it.

Music will be always be my first love. I wrote and published music in my teens and twenties before I took my first creative writing workshop. I only took that writing workshop because I’d come to some stopping place. I didn’t know whether I wanted to be a classical or pop musician, and if I only had, say, the example of someone like Björk, who hybridizes the two, then I’d probably still be a musician today. I became interested in writing because back in the day I liked the idea of playing all the parts. As a writer I could be the percussionist, the string section, and the vocalists, and I didn’t have to worry about my collaborators. I still look to other musicians for energy as much as I look to my favorite writers. I want aspects of my own writing to approximate the irregularity of a shifting time signature or the shock and delight of a key change. Music knows how to encode the unexpected, as well as every shade of emotional complexity at a single second, in a single chord. I don’t know how it’s possible to be a writer and not be attuned to the way a singer phrases. I’m not saying that as a pronouncement, but I wouldn’t know how to string words together if music weren’t at the center of my life.

What do you think of pronouncement in relationship to craft? It’s so clear from your writing that you’re an independent, self-attuned thinker, but, like many of us, you have an MFA. Not every MFA Program is orthodox when it comes to matters of craft—and yet coherence, consistency, control: those ideas are wired into the system. Taught not just by instructors but by one’s peers as well. Could you talk about that? Was there a point when you found yourself interrogating what you’d absorbed?

CLB: I entered an MFA program thinking of myself as a self-taught writer. Most of my education as a writer prior to grad school was punk, experiential: writing to perform in spoken word or multi-media performances. I learned by the sound of it. In my MFA program I was confronted by how little I knew formally about writing. I was already making work and publishing, so I didn’t need an MFA program to anoint me a writer. I had a sense of solidity enough that I could be open and expand and also sense for myself when my instincts for a project might be better than what everyone else is telling me what to do. In terms of interrogating what I absorbed through formal study of writing; I mostly saw it as a gift. I wanted to teach, so I needed the degree, but more so I needed an interruption from my paycheck-to-paycheck life so I could figure out how to carve out a more significant writing practice for myself.

I learn so much about writing craft through teaching, through reading, and through listening to other writers talk about their process (David Naimon’s Between The Covers podcast is like a free MFA program) and this less “professionalized” way of engaging with craft feels more organic to me. Some friends took me surfing for the first time on the Oregon coast a few summers ago, and we rented gear from a little surf shop on Cannon Beach. The owner of the shop piled up a wetsuit, booties, gloves, a leash, and a chunk of board wax into my arms and he said, “There, now you got everything you need to get yourself drowned.” And this is what it’s like learning, all at once, a bunch about literary technique and craft. You have everything you need to get yourself drowned, but hopefully instead you’ll figure out a way to stay afloat in it, and still see what drew you to the work of writing and what you came to say without getting subsumed by what you now worry you “should” do when you write. It’s important to figure out how to stay wild in the face of an MFA.

…

You mentioned that Later was a project you’d put aside and came back to. How do you generally work on a project or projects, and what does the physicality of your writing practice look like?

PL: My sense of process changes from book to book, and I want to make sure I don’t let my habits control my thinking or the structure. With Later, I began with a linear structure that seemed foreign to how I usually work. I remember thinking, am I this writer now? But before long I felt suspicious of the ease of it. I suspect now that the structure was leading me toward a kind of thinking that wasn’t mine. I was losing my book, even though I usually think it’s desirable to lose one’s book at some point. But you want to lose it to an energy that feels fresh and wild. I put the book aside for a while—I wondered if it was just going to be another half-baked idea, something I’d learned from in order to write the next project. I went back to it and started both stretching and compressing. It involved playing with tense, interrupting it with short sections (glimpses vs. fully embodied scenes), a thinning out of the boundaries between past, present, and future. I wanted those three levels of time to feel implied inside the same room. So, the process was about testing from sentence to sentence until it sounded right, until I could speak whole parts of it aloud and it managed to mesh with my breathing patterns.

“Every writer has lost projects—projects you might have dreamed about for years; projects you tried and just couldn’t pull off.”

The Narrow Door was much different. That book roves all over the place in terms of content and date but the structure was written in clock time. The structure you see on the page is really faithful to a year-long record of grief and dislocation—I didn’t muck it up that much and when I tried to regularize it, it refused to behave. Some of the events in that book are written days after they happened. I wondered whether the book was in charge of my life and if it was my duty to be a transcriber and deal with the consequences of what it was already fastening in language.

There are pieces in Unbuilt Projects that I literally forced into being because I’d read somewhere that Lydia Davis had done that once or twice with some of the pieces in Varieties of Disturbance, and I thought, well if she can do it? So now you can see that I am in no way a stable, reliable animal!

Every writer has lost projects—projects you might have dreamed about for years; projects you tried and just couldn’t pull off. Projects you think you’ll come back to on a better day. Could you talk about some of your unrealized projects?

CLB: One of my “lost projects” that I don’t want to relinquish is a monograph on the artist Pippa Gardner, who I came to know when I lived in Santa Fe, NM. She is an amazing character: a trickster, practical joker, and inventor. She illustrated for Car and Driver Magazine for years, but she doesn’t drive. I used to see her self-ambulating around town on one of her human-powered machines. I once rode the Santa Fe Century, a 100-mile bicycle race around the surrounding villages, and I overtook Pippa on one of the longest mountain passes as she pedaled a soap-box derby looking car up the highway. Her embodiment as trans always struck me as an extension of her artistic practice.

What are your lost projects? And do you think they’ll be found, eventually?

PL: I’ve put aside more than a couple of books, my first novel, which was as much about the setting of southwest Florida and the Everglades as it was the characters, Then there was multi-voiced novel that occupied me for the better part of the 2000s. I wanted it to feel choral, and all the life was in the subordinate voices, but the primary voice? It felt too much like my mouthpiece, and yet the character was so much more humorless and sincere than I’d ever be in my actual life. The better parts of that book ended up being central to The Burning House and Unbuilt Projects, so it wasn’t a loss. I learned so much. But it was such an odd experience. I think I felt more of an obligation to write that book than an actual gut-level imperative.

I also have a book about my relationship with animals, but I haven’t yet been able to put animals at the center of any long nonfiction narrative with any satisfaction. It feels too willed; it’s trying to look straight ahead at the unsayable when I think the unsayable belongs in the margins, if even there.

__________________________________

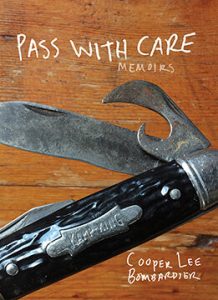

Pass with Care by Cooper Lee Bombardier is available now via Dottir Press.