Writing About the Small Farming Life in the Shadow of Climate Change

Patrick Laurie Finds Inspiration in the Writing of R.S. Thomas, Seamus Heaney and Ted Hughes

In the shadow of climate change, books about farming have become more popular. It stands to reason that consumers should focus on food production at a time when the world feels unstable, but it’s also clear that agriculture has played a part in the emerging crisis. That’s a neat paradox, but when it comes to literary portrayals of farming, many readers have a clear idea of how they’d like food to be produced. That has often meant that solutions to sustainable food production are bound up with cultural perceptions of what the land should be—and particularly what it used to be.

To my mind, the significance of “old-fashioned” farming was laid down by writers in the 1950s and 60s who captured the last glimmer of traditional agriculture as it was. Following their ideas, I’ve begun to see how literary representations of agriculture can evoke much more than comforting nostalgia.

I’ve been writing and farming in Scotland for more than ten years. I chose to set up an old-fashioned business based on traditional breeds of cattle, and I have a strong belief in low inputs and slow outputs. As my neighbors have ramped up commercial production in the glen where I live, my land has been managed according to techniques laid down in the 18th century. As the world gets faster, I’ve been working hard to slow my small piece of it down. Perhaps that sounds obtuse, and maybe it was to begin with. I’m naturally preoccupied with Scottish history, and my old family connections with this place made it feel pressingly personal. But alongside the physical graft of farming, stepping back in time through books and poetry has set me on a path which feels powerfully relevant to conversations about future food systems.

I’m deeply inspired by the writing of R.S. Thomas. A strange and austere Anglican priest, Thomas wrote poetry about agricultural communities in the Welsh uplands, and his descriptions of farm life are unmistakably bleak. Crooked, lonely figures labor at endless tasks in an ancient landscape; they prove a sense of themselves in the simple act of existing. The enormity of that very human struggle lies right through my experience of farming, but Thomas’s poetry is not clearly aligned with religious or philosophical moralities; it explores a kind of holiness which derives value and meaning from the simple, stubborn act of clinging on.

Through the recurring everyman character of Iago Prytherch, Thomas peels back the layers of modernity to reveal the formative essentials of humanity, framed in the act of penning sheep and ploughing fields “in a gap of cloud.” It’s rich, rough and wholly authentic, and it makes a perfect counterpoint to the reality of my days working with cattle in the endless rain. Thomas is right; farming can be hard and lonely, but that heightened sense of darkness can add a stunning luminescence to the sun’s return.

R.S. Thomas was concerned with the demise of hill farms during the course of his life. I think his best rural poetry was published in the 1940s, but he continued to express concern at the loss of old traditions until his death in 2000. A fervent Welsh nationalist, he found something deeply valuable in that relationship between people and place. I share Thomas’s sense of urgency and outrage at the loss of old traditions in the hills; his work is endlessly inspiring to me, but despite his protests, those traditions died anyway. They have been replaced by a kind modern farming which frequently lacks that cool sense of deep connection.

I recently visited Bellaghy, the town in Northern Ireland where the poet Seamus Heaney grew up. The son of a cattle dealer, Heaney’s early poetry is full of blunt agricultural language which established a sense of connection with his readers. Compared to Thomas, Heaney’s work was less preoccupied by change, but it does feel strangely out of date to modern readers. The symbolism of milk churns, water pumps and linen beetles had power and relevance to people born and raised in the 1930s, but these objects are now functionally redundant; they belong in a museum. Heaney’s poetry is still relevant today, but it has acquired a vintage aesthetic. It’s odd to realize that the poet’s agricultural world had broad appeal because it harked back to a time when most people had a practical, hands-on relationship with farming.

By comparison, modern mechanized agriculture has become a highly specialized and niche industry; it’s hard to write about grain varieties and subsidy spreadsheets without alienating the general reader. In 2019, it was estimated that only one percent of British people work on the land. The loss of those old associations has an enduring cultural impact.

Seamus Heaney’s background in farming proved to be the foundation of his reputation for a broad and stable wisdom. It’s interesting to compare him to Ted Hughes, who was brought up around farms in West Yorkshire. The two men were friends, but where Heaney was calm and emotionally grounded, Hughes is richly mercurial and elusive. His subjects leap and roll across the page, and his presentations of farmers and farming are wired in to an electrical connection with folklore, mythology and magic.

Hughes’s 1967 short story Sunday is based around an old farm worker called Billy Red who is able to catch and kill live rats using only his teeth. It’s a horrible tale, but it’s madly hypnotic and addictive. I go back to reread it every couple of months with mixed feelings of curiosity and dread. Rats would go on to become a recurring motif in Hughes’s agricultural writing, particularly as he began to depart into ideas of shamanic spiritualism. I can wholly relate to his descriptions of working every day with cattle, using techniques which have not changed for centuries; knowing the beasts inside-out and examining that strange tension between animals both as spiritually entire companions and food. As a reader, you can feel the time and patience he invests into that understanding. Even with the best intentions, that time that is hard to justify on modern farms.

Thomas, Heaney and Hughes respond to the changes in farming in different ways, but their legacy reveals a shared sense that as we advance towards ever greater productivity, we take dangerous shortcuts. I’ve discovered at first hand that old-fashioned farming was difficult. Modern technological advancements have made life so much easier, and the old ways seem pathetically wasteful and inefficient by comparison. When it comes to my own farm, I’ve taken the clear decision to step back towards an older time, but the world would suffer badly if all farmers did exactly what I have done.

Even since the days when Heaney, Hughes and Thomas started writing, the global population has increased by five billion hungry mouths. What I’ve done is not offered as a blueprint or a way ahead for modern agriculture. My project is a genuine reappraisal of those traditional standards which seemed to offer so much more than simple productivity.

The ecological impact of agricultural intensification has been disastrous. Birds and wildlife have foundered, and many would argue that in the struggle to maximize quantity, we have even seen a drop in the quality and richness of what we produce. But intensification has also led to a disaster in ourselves, and something that amounts to a crisis of the imagination. There is a profound holiness to the growing and tending of food. It’s a fundamental expression of our humanity; our sense of community and connectedness.

It’s there in Heaney’s earthy pragmatism; in Hughes’ animal witchcraft and the gloom of Thomas’ secular-spiritualism. If these things were birds, we’d have a thousand charity organizations devoted to their conservation. Instead, they’re allowed to wither and vanish in the panicked pursuit of “more by any means”. That’s why most of my farming mentors are literary figures, and why I love to walk amongst my cattle in the moonlight as my grandfather did as a boy more than a century ago.

Conservationists have become adept at finding ways to integrate biodiversity into commercial farming systems, acknowledging the demands of a hungry world. I’d like to do the same for spirituality, imagination and magic. It’s tough to retain a sense of humanity in this industry, but the first step is to remember that farming is a fundamental expression of ourselves.

___________________________________________________

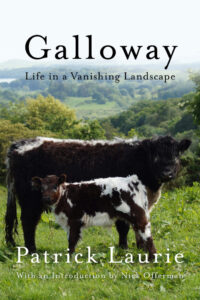

Patrick Laurie’s Galloway: Life in a Vanishing Landscape is on sale November 16, 2021 through Counterpoint Press.

Patrick Laurie

Patrick Laurie was born and brought up in Galloway. After gaining a Master of Arts degree in Scottish Language and Literature at the University of Glasgow, he moved to the Isle of Harris to work on hebridean fishing boats. Since 2010, he has balanced freelance journalism with farming and conservation projects in Galloway and the northern part of the UK.