Writing About the Forgotten Black Women of the Italo-Ethiopian War

Maaza Mengiste on Gender, Warfare, and Women's Bodies

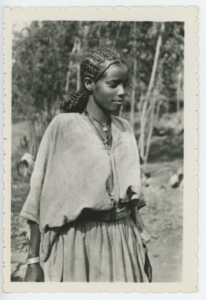

I own a picture of a young Ethiopian girl whom I have started to call Hirut. She is in her teens, and her hair is pulled away from her face and hangs down her back in thick braids. She wears a long Ethiopian dress and even in the aged, black-and-white photo, it is easy to see that it is worn and stained. In the photo, Hirut has turned from the camera. I imagine that she is looking down at the ground, doing her best to focus her attention on something besides the intrusive photographer who is beside her, getting ready to shoot.

I have given her a rifle that is the last gift from a dying father, and her fate will be tied to a promise she made to never let it out of her possession. There is a war coming into Ethiopia and she has been told that she must work with the other women to prepare supplies for the men who will fight. It is 1935 and Hirut is orphaned and she has never gone further than five kilometers from her home. When they say: We must defend our country, Hirut wonders to herself: How big is a country? And she will continue to ask this question as Benito Mussolini invades Ethiopia and she is pushed—by decisions wholly her own and not entirely of her making—closer and closer to the front lines until she is holding a rifle and pulling the trigger and wishing all her enemies dead. This is the premise of my novel, The Shadow King.

Just how much can a picture tell us? Photos of Ethiopian girls and women were used to entice Italian men into joining Mussolini’s army. The soldiers were promised a quick war and an African adventure. They marched into Ethiopia singing songs of what they would do to Ethiopian women. Many packed their cameras along, eager to document this great journey that was surely the farthest that most had ever been from home. I have been collecting their photographs for well over a decade, poring over images—of quotidian military life, of deliberate brutalities, of friendships and camaraderie—to find what they may have never intended anyone to see.

I have sat for hours at a time staring at the faces of Ethiopians—men, women, children—who were forced to live with the occupying force. I have tried to read what hovers just out of view. That overly stiff posture of an elderly man next to a relaxed and smiling Italian soldier might hint at deep fear and discomfort. That bruised mouth on a prisoner pointed to ill-treatment, regardless of the casual arm around that prisoner’s shoulder. Those rows of girls, staring bare-chested and blank-eyed into the camera, might be saying more with their remote gazes than any shout for help could convey. That woman in her long dress staring into the camera with defiance might know more about what lurks in the hills behind the photographer’s shoulder than he does.

I was aware, even as I looked at these photos, that they were made by men to shape and reshape their memories. In photographing Ethiopian civilians and prisoners: men and women, boys and girls, these Italian men were re-imagining themselves. Like those familiar photographs that colonialists sent back from the territories they claimed needed “civilizing,” every picture became a narrative that he was creating about himself, about war. What, then, could I really glean from these images? What survived after sifting through the crafted narrative held within each photographer’s frame?

In The Unwomanly Face of War, Svetlana Alexievich states that, “Everything we know about war, we know with ‘a man’s voice.’ We are all captives of ‘men’s’ notions and ‘men’s’ sense of war. ‘Men’s’ words. Women are silent,” she contends. I was not sure that women were silent, but I did know that they were not heard. What would it mean to tell a war story with a woman’s voice, with her sense of war, with her notions of what it means to be a soldier? I went back to the photographs in my collection and began to isolate those that specifically depicted women. I glanced away from the male photographer, drew the girls and women around me, and bent towards them to listen. What could they tell me about Hirut?

Photos of Ethiopian girls and women were used to entice Italian men into joining Mussolini’s army. They marched into Ethiopia singing songs of what they would do to Ethiopian women.

I built my story of Hirut and the Italo-Ethiopian war of 1935 in increments, folding archival research into my own readings of the photographs I was collecting. I set pictures with discernible locations onto a map of Ethiopia, pinning those that I could to dates and battles, recreating historical moments out of fragmented information in order to understand the intimate, personal details that I thought I could detect. What started to crystallize and sharpen in front of me was often breathtaking: a series of lives, once held immobile and silent between shutter and aperture, stepped out of the shadows of history and into brighter light. They lent me words. They pointed me in new directions. They pushed those photographers further away, full of indignation and fury, and beckoned me on towards uncharted terrain—towards their war. Following their lead, I began to write my book.

I had no idea when I sent my fictional Hirut to war that my great-grandmother, Getey, preceded her: flesh and bone, blood and pride, paving the path for my imagination. I did not realize, when crafting Hirut’s story about losing possession of her father’s gun, that my relative Getey had experienced something similar. My great-grandmother’s story was a discovery made during a casual conversation with my mother, one of those moments when she stopped me as I was telling her about one of my photographs to say, But don’t you know about Getey, your great-grandmother? Don’t you remember?

What I remembered were all the stories that I had heard growing up, stories of men going to war: those proud, ferocious fighters who charged at a better-equipped, highly weaponized army with old rifles while barefooted and dressed in white. I imagined these men, so simple to spot, charging into valleys and flinging themselves at the invading foreigners, their throats grown hoarse from battle cries. My imagination tethered all the stories into an extended narrative, the images spinning in front of me then looping when I reached the limits of my comprehension. In this war, men stumbled but did not fall. Men gasped but did not die. Those white-clad men ran towards bullets and tanks, heroic and Homeric, myths brought to life. I would shut my eyes and see it all unfold: a thousand furious Achilles’s shaking off that deadly cut and rising onto undamaged feet again and again. I remembered the war like this, told in what Alexievich calls “a man’s voice,” regardless of who did the telling.

My great-grandmother, Getey, was a girl in 1935 when the Italian Fascists invaded Ethiopia. As war loomed, Emperor Haile Selassie ordered the eldest son from each family to enlist and bring their gun for war. There was no son in Getey’s family who was of fighting age. She was the eldest, and not even she was considered an adult. In fact, she was in an arranged marriage but too young to live with her adult husband. In order to fulfill the emperor’s orders, her father asked her husband to represent the family, and he gave the man his rifle. This act must have felt like a final betrayal to her. (Eventually, she would leave this arranged marriage and a husband she did not like.) She rebelled and told her father she would enlist in war and represent her family. She was, after all, the eldest. When her father refused, she took her case to court and sued him. And she won.

When the judges announced their verdict, she raised the rifle above her head and sang shilela—one of the songs that warriors sing just before battle, when they meld their fearlessness and fighting prowess into melody and rhythm. Then she took the gun and went to join the front lines.

*

I knew Getey as an old woman, essentially bed-ridden but alert. I have no solid memory of what she looked like: to my child’s eye, she was simply old, a petite woman with skin molded almost entirely out of gentle wrinkles. The day I came to visit her, not long before she died, I spent most of my time with other relatives who had gathered in the home she shared with her daughter. I had my camera but I did not take any pictures of her. She was in bed, tucked into a corner of the house, isolated from the talk and revelry happening in the other room. Though stories about her stubbornness and spiritedness had seeped into the descriptions I heard of her, I knew nothing back then of her experiences during the war. She had been relegated to the position of a respected elder, someone gazed upon through the thick haze of time, discernible but essentially unseen.

After learning Getey’s story, what I had suspected from my examination of photographs and news articles solidified into tangible knowledge that came from my own family and coursed through my blood. Women were not only the caretakers in the war against Italy and the fascists; they were also soldiers. Even though it was difficult to find these stories, the more I researched, the more women I found tucked inside the lines of history. A photo here, a headline there, a short article over there. The process was often slow and frustrating, but it was undeniably exhilarating. We were there, I found myself thinking. We were there and here is proof, and I imagined Getey stepping in front of me, rifle raised, a song in her throat, and pushing me forward. Because: how many more were there, waiting to be spoken into being?

Myth: That war will make a man out of you. That aggression—and anger—is the territory of men. That in conflict, the sisters of Helen will wait breathlessly inside the gates of Troy for victory or defeat to decide their fates. That when we speak of war, we speak of tested resolve and broken spirits and wounded bodies and imagine them as masculine figures clad in uniform: filmic images drifting past our imagination, buoyed by stories and textbooks and literature. Yet there is Getey, look at her slinging that rifle over her shoulder, saying goodbye to her younger brothers and father, and marching to the front lines.

Myth: That war will make a man out of you. That aggression—and anger—is the territory of men. That in conflict, the sisters of Helen will wait breathlessly inside the gates of Troy for victory or defeat to decide their fates.

Fact: Women enter into struggle, whether political or personal, well aware of the bodies in which they exist. We recognize our strengths even as we are reminded of the ways we can be made vulnerable. We know that the other battlefield on which another kind of war is fought is the one bordered by our own skin. No uniform or alliance can completely erase the threat of sexual assault and exploitation that wants to make us both trophy and contested territory.

Imagine Hirut on the top of a hill, rifle ready, prepared to ambush the enemy. Along the way to this war, she is forced to contend with sexual aggression and then rape by one of her own compatriots. The smoky terrain of the front lines has expanded to engulf Hirut herself: her body an object to be gained or lost. She is both a woman and a country: living flesh and battleground. And when people tell her, Don’t fight him, Hirut, remember you are fighting to keep your country free. She asks herself, But am I not my own country? What does freedom mean when a woman—when a girl—cannot feel safe in her own skin? This, too, is what war means: to shift the battlefield away from the hills and onto your own body, to defend your own flesh with the ferocity of the cruelest soldier, against that one who wants to make himself into a man at your expense.

Helen of Troy, gazing across the bloody battlefield of the Trojan War, cannot imagine herself independent from the men who wage war in her name. When that great Trojan warrior, Hector, approaches her, she looks at him and understands that she is as much bound to the battle unfolding beyond the gates as any soldier. She laments the decisions of the gods, of Zeus, who have turned her body, her self, into a catalyst for conflict. “Hereafter we shall be made into things of song for the men of the future,” she tells Hector in Homer’s The Iliad. She can never extricate herself from the war. She will never have an identity beyond that of prized possession and stolen treasure, something to be reshaped and reconfigured, and then sung by men well into the future. She may not have known that while she mourned her fate, Pentheselea, that mighty Amazon warrior, would soon stand bravely in front of Achilles and wage battle with such unrelenting ferocity that Achilles would mourn while killing her, sensing a fighting spirit like his own, perhaps.

While developing Hirut’s narrative, I read the stories of female soldiers from across the centuries. From Artemisia of Caria in 480BC to the women in the army of the Kingdom of Dahomey in early 18th century Benin, to the more recent Yazidi women’s army that fought against ISIS, I have come to realize that the history of women in war has often been contested because the bodies of women have also been battlefields on which distorted ideas of manhood were made. If war makes a man out of you, then what does it mean to fight beside—or lose to—a female soldier? For centuries, women have been providing their own answers to this. But history—that shape-shifting collection of memories and data replete with gaps—would want us to believe that every female soldier plucked out of oblivion and brought to light is the first and only one. But that has never been true, and it is not true now.

__________________________________

Maaza Mengiste’s The Shadow King is out now from Norton.

Maaza Mengiste

Maaza Mengiste is a novelist and essayist. Her debut novel, Beneath the Lion’s Gaze, was selected by the Guardian as one of the 10 best contemporary African books and named one of the best books of 2010 by Christian Science Monitor, Boston Globe and other publications. Her fiction and nonfiction can be found in The New Yorker, Granta, the Guardian, the New York Times, BBC Radio, and Lettre International, among other places. She was the 2013 Puterbaugh Fellow and a Runner-up for the 2011 Dayton Literary Peace Prize. She currently serves on the boards of Words Without Borders and Warscapes.