Writing About My Alcohol Addiction Helped Treat It

Clare Pooley on Writing Her Way Up From Rock Bottom

My rock bottom moment was not particularly dramatic. It didn’t involve policemen, lawyers or even a hospital. Rather, it came courtesy of a novelty mug, which I’d filled with red wine to take the edge off my hangover, at 11am. This was a first, because not drinking until after midday was one of my rules. It was one of the ways I was able to convince myself that I wasn’t an alcoholic. And I’d broken it.

That in itself might not have been enough to shock me into taking some action, but what was written on the mug I was holding was. It read: THE WORLD’S BEST MUM.

My drinking had crept up almost imperceptibly. One large glass at “wine o’clock,” because it was “me time,” turned into two. Two gradually morphed into three, and when your glasses are as large as mine were, that’s a whole bottle, every day.

By this stage, I was a terrible insomniac, anxious all the time, 30 pounds overweight and my life was stuck in a rut. The worse things got, the more I self-medicated with wine. The more I self-medicated with wine, the worse things got. I was stuck in the middle of a never ending negative feedback loop.

The sensible thing to do would have been to ask for help. I should have called AA, or found a rehab facility, or at least confessed to my family and friends. But I was far too ashamed to do any of those things. I’d spent decades constructing an elaborate carapace around myself, curating a social media feed that conveyed the perfect life I wished I had, and I wasn’t ready to admit to anyone that it was all a sham.

Instead, I began to write.

As a child and a young adult, I’d loved to write. I wrote in a journal, every day. It was the usual melange of hormonal angst and school gossip, with some opining on the news items of the day thrown in to prove that I was, despite appearances, an intellectual. I wrote soppy love stories which I sent to my favorite magazines, who sent them back with the instruction to buy a typewriter. But, by the time I left university and started a career in advertising, I’d stopped writing. I took the dream I’d had of one day becoming a novelist and stuffed it in the back of my wardrobe with some mothballs.

For more than two decades I wrote nothing apart from shopping lists, emails, PowerPoint presentations and the occasional web copy that the copywriters deemed not worthy of their talents or time. But on that day, the day of the shaming mug, I felt an overwhelming urge to write, and I haven’t stopped since.

Since it was now the 21st century, I decided not to write in a journal, but to do it online. With the help of many Google searches, I managed to set up a rudimentary blog which I called Mummy was a Secret Drinker, under a pseudonym—SoberMummy.

Addicts talk about having “monkey brain,” the endless chatter in your head that can make you feel like you’re going crazy, and renders it impossible to concentrate on anything else. When you first quit drinking, that chatter gets worse. I found myself constantly obsessing about booze, and playing the movie of my life back over and over again, trying to work out how and why it had all gone wrong.

Writing was my way of corralling all of those out of control thoughts, of lining them up, making them behave, then pinning them down on the page. Writing was my mindfulness, enabling me to stay in the moment—without having to learn how to chant, or to sit still doing nothing—something I found impossible to do.

Writing was also my degree in addiction studies. Every day I would research what I was going through—using every source material from memoir and lurid news reports to academic papers—and I’d share my findings on my blog. I researched everything from the way alcohol affects our sleep, our skin, our weight, even our hair, to its links with cancer, depression and Alzheimer’s.

Writing gave me the clarity that comes with objectivity. Just the act of writing down my issues distanced me from them. It felt almost as if they were happening to someone else, and it’s always easier to counsel someone else wisely than it is to advise yourself.

Then, writing became my group therapy. I didn’t publicize my blog at all—I was far too scared of being found out, but still people found me. Thousands of them. Within a year my blog had had nearly a million hits. And those people, who told me again and again that my life story was also their own, became my support and kept me accountable.

I didn’t publicize my blog at all—I was far too scared of being found out, but still people found me. Thousands of them.

When, eight months after I started writing, I found a lump in my left breast, I didn’t call my husband, or my mother, or my friends. I didn’t want to terrify them, as well as myself. Instead, I reached for the same prop that had got me through my first eight months sober. I picked up my laptop and began to type.

I told my readers everything—exactly how it feels, when you have three small kids, to be handed a potential death sentence—and over the next few months of agonizing tests and grueling treatment, those virtual friends kept me going. In the middle of the night, when I was tossing and turning and contemplating my own mortality, I would receive messages from readers in Australia and New Zealand who were on their lunch breaks. They’d share their own stories, of cancer beaten and lives restored. A wonderful woman in Wisconsin, half a world away, told me that her whole church congregation, 250 people, had prayed for me—a woman she’d never met and whose real name she didn’t even know.

I came through the cancer, and being sober became the new normal. But I still need to write. Every day, obsessively. So, I began writing fiction. I thought back to the time when the reality of my world was so very different from the way I portrayed it. I remembered the way telling my authentic story had changed my life, and the lives of thousands of strangers all over the world, and I wondered what would happen if everyone told the truth?

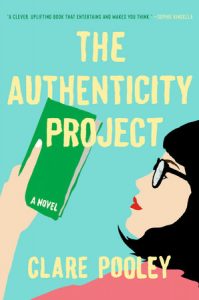

That thought led to my debut novel—The Authenticity Project—the story of a little green notebook in which a 79-year-old artist, Julian Jessop, tells his truth and asks the finder of the book, which he leaves in a café, to do the same. The book is passed between six strangers, transforming lives and creating magic and romance as it travels.

Each of my characters has a central flaw—Julian is self-obsessed, Hazard is an addict, Monica is a control freak and Alice is struggling with motherhood and a reliance on social media. As I wrote my story, and came to love each of my troubled fictional friends deeply, I realized that it’s these flaws that make them all real, unique and lovable.

It was my teenaged daughter who pointed out what I’d done.

“Mummy,” she said. “You do realize that these characters are each an aspect of you?”

I thought that I’d moved on from writing as a form of therapy, but it turned out that I had taken all of my (many) flaws and explored them on the page. I had given them life, names, backstories, hopes and dreams. And, in doing so, something miraculous had happened.

In learning to love them, I’d learned how to forgive myself.

__________________________________

The Authenticity Project is out now from Pamela Dorman Books.

Clare Pooley

Clare Pooley graduated from Cambridge University, and then spent twenty years in the heady world of advertising before becoming a full-time writer. Her debut novel, The Authenticity Project, was a New York Times bestseller, and has been translated into twenty-nine languages. Iona Iverson’s Rules for Commuting is her second novel. Pooley lives in Fulham, London, with her husband, three children, and two border terriers.