Writing a Novel in the Age of Peak Content

Notes from the Midst of A Terrifying Digital Flowering

Everything is apparently peaking. Peak TV, peak beard, peak craft beer. We’re living in the age of a glorious cultural crescendo. We have more music, more movies, more magazines, games, food, and platforms than ever before all vying for an orifice. We’ve reached peak media, the pundits say, peak content, peak attention. If it weren’t enough, amidst it all, today, a feckless pussy-grubbing con man conducts world affairs from an armchair with a storm of broken Tweets. Newsrooms scramble to gather up each inanity into ever-more damning headlines while on the sidelines we read that we’re approaching peak dad, peak democracy, and, well, peak peak.

Befuddled, still lusting for the lurid, longing for further climax, I swipe away and dig like a rabid dog through my feed, searching for that tasty morsel, that final headline that will confirm—Praise Be—that we’ve at last hit peak Trump: “DNA Testing Proves that the Semen Sampled from the President’s Lapel Belongs to Putin!!” But the headline hasn’t arrived (Fake News), so I keep on clicking and read that global emissions must peak by 2020—impossible—and online retailers must be peak-proof—unlikely—and peak oil is actually, like all non-geologic peaks, probably a myth or marketing ploy. As George Monbiot observes: “There is enough oil in the ground to deep-fry the lot of us, and no obvious means to prevail upon governments and industry to leave it in the ground.”

The same might be said of so much content. There’s already enough to burn out every last Gb of brain power and no obvious means to prevail upon media outlets—even this one—to let it all languish upon some crappy laptop.

Amidst this terrifying digital cultural flowering, my reading life has withered. Over the past year, I have read far, far fewer books than any other year since my reading began in earnest around 18. Today, I can tally the year’s titles on ten fingers. I suspect I’m not alone in such a dismal figure. Who can really donate sustained attention to 200, 300, 343 (!) pages these days? I mean, I do want to learn if little Willie Lincoln made it through the Bardo but, sorry Mr. Saunders, the Sierra Club just pinged me. I can’t be bothered. “Now more than ever,” they say, and so too the ACLU, the Arts Action Fund, et al. “Your donation matters.”

Now more than ever, the impulse to read a book, let alone write one, seems preposterous. How could anyone toil for years on a single piece of content? “You ask yourself, why am I bothering to write these books?” the esteemed Jonathan Franzen, author, according to Time, of the Great American Novel Freedom, mused in 1995. Franzen was reflecting on the gap between the broad critical splash his first book seemed to make and the rather shallow ripple it offered popular culture.

Franzen attributed it to the overwhelming glut of ephemeral and disposable media. The solid artifact, the object of the author’s craft, the book, especially a difficult book, could not compete with so much content. The fact that he bemoaned the crisis in 1995 seems precious now. “This is just entry level to what’s coming,” Cormac McCarthy said a decade later. “I don’t care whether it’s art, literature, poetry or drama, whatever . . . the appalling volume of artifacts will erase all meaning that they could ever possibly have.”

The drive to write, to curate prose within the bounds of a hardback that one hopes will last, and perhaps, add some fire or fuel to the human condition, today appears the doomed enterprise of dusty dupes. Why do we write? “One goes on writing purely out of habit,” W.G. Sebald reflected around the same time, “it’s unclear whether writing renders one more perceptive or more insane.” In such an environment, nothing seems more ludicrous, more of a waste, than the attempt to write a book.

Perhaps it’s appropriate that I finished mine hunched over a toilet. The bathroom was at the back of a cramped vintage women’s clothing store and the manager, a friend, let me plug the computer in behind a rack of dusty sixties dresses and stretch the chord beneath the door and keep my laptop perched between the windowsill and water heater. I didn’t plan this, it just worked out that way. One needs a room of one’s own. She was rarely busy, and she was a friend, as I said, and shortly after I finished she went out of business (#PeakVintage).

My book—I pitched it to her and publishers as a YA Lesbian Vampire Novel—was actually, broadly, about climate change and solar geoengineering and it received initial positive reviews like Franzen’s first book but ultimately hasn’t triggered any tsunami splash. While writing perched above the toilet I often worried about electrocution and wondered, in the context of so much disposable content—Why? What was the purpose? “I write to find out what I’m thinking about,” Joan Didion once theorized in a formula that sounds rather circular. “I am not schizophrenic,” she suggested. I followed her prescription: “You just lie low . . . stay quiet . . . keep your nervous system from shorting out . . . ”

The research for the book required me to click through an overwhelming amount of content, and I often wondered if consuming so much information rendered me more perceptive or insane. I tried to translate this anxiety to the text. The onslaught of voices, quotes, numbers, and sampled texts, the fragmented form, given to jump cuts and juxtaposition, and the dizzying structure and subject matter—mashed equally between the global and the personal—all of this I hoped might mirror the uncertainty and chaos we face in a world that bombards us constantly with so much information, ideas, so many articles, images, and cultural noise that we can scarcely recall how we arrived here, never mind construct a coherent portrait of the present moment, or suggest a plausible narrative forward out of its impasse.

“We are a species in despair . . . ” Sebald said during the same interview, before he died of a brain aneurysm. We have created an environment that “isn’t what it should be. And we’re out of our depth all the time.” So we keep clicking, tweeting, the entire tribe of birds bangs on in fevered crescendo, desperate to pass on through the trees some final update before collective apoplexy. “We’re living exactly on the borderline between the natural world from which we are being driven out, or we’re driving ourselves out of it, and that other world which is generated by our brain cells.”

Peak Nature. Peak attention. “I’m not schizophrenic, nor do I take hallucinogens . . . ” There’s a reason people keep doing this digital detox thing. We’ve created a globalized technological world that our hunter-gatherer brains are no longer adapted to in a genuine Darwinian sense. But such a truth won’t pay the bills—after detox it’s time to dive back in, back to business, back to madness. Has humanity passed its peak? “I don’t know what of our culture is going to survive, or if we survive,” McCarthy said in the same interview. The scientists at the Santa Fe Institute hadn’t given him a specific date for our demise, and I don’t have one either. But I can tell you that many climate scientists aren’t particularly optimistic. As Ken Caldeira, an atmospheric scientist at Stanford’s Carnegie Institute for Global Ecology who ran some of the initial solar geoengineering models, told me during the writing of my book: “It’s all uncertainty.” That’s the human condition I guess. Caldeira told me at the time that we could have a full-scale solar geoengineering deployment online and ready within a year. He told me not to worry. The termination problem was exaggerated. “I think we’ll muddle through it, or at least the rich will make it okay.”

I wouldn’t describe myself as particularly rich—certainly not in optimism or US dollars. But relative to the world’s poor, I suppose I’m doing well, which is very sad, but hey, the World Economic Forum says we hit peak well-being this year. Cheers to milestones. What can you do? I try not to pollute the pond too much, to limit my impact as a consumer. There’s something intolerable for me about buying new stuff—not because of the money, but because there’s already so much shit, so many consumer goods, too much content, too many people. I’m not alone in this aversion. The CEO of IKEA says the western world has hit peak stuff. We don’t need anymore candle holders apparently. And on the rare occasion that we do—well, I just go to Goodwill.

Thrifting tracks with my longing for authenticity. I can be a savior instead of consumer. If I can rescue a cute vintage spatula from the piles of oblivion I have subverted the culture of crass consumerism and my purchase and reuse places the planet on a more sustainable path, even if the gas consumed in traveling between seven thrift stores far outweighs the carbon footprint of a similar spatula I might have purchased new and for cheaper elsewhere. But never mind, I like thrift stores. I like the smell of stale skin cells. I like the old blood drive t-shirts, the photo frames of failed marriages, the appalling volume of broken televisions, coiled USB cables, and coffee mugs. I like the congenial multicultural marketplace vibe, the banal analgesic 90s soundtrack raining down from the rafters, the unhurried unpretentiousness that attends casual picking. None of it should go to waste. And while I’m constantly addicted to consuming fresh content on my Pixel, constantly testing the wind for some whiff of what the future may hold, I tell myself, picking through the crusty piles of old flip phones, like Sebald, “dust has something very, very peaceful about it.” There’s something therapeutic about thrifting and “something terribly alluring to me about the past. I’m hardly interested in the future. I don’t think it will hold many good things.”

Perhaps my penchant for the old and obsolete might explain my fondness for writers like Sebald and McCarthy with a somewhat archaic, even dusty, prose style. It’s the hunt for these authors’ books, and others, in hardback first edition, that primarily drives me to the thrift store. In general, I do have enough candle holders. Despite my recent paltry reading habits, I’ve kept on buying books as frequently as I’d like to be reading them. Over the past few years, I’ve amassed an impressive collection of thrift store firsts. It’s a hobby, however, similar to hard archeology—think of those decade long desert digs—that requires some patience. It can be frustrating to always see S-E-B-O, O—Oh!—it’s The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold. Not Sebald. Or it’s Mary McCarthy’s The Group, not Cormac. Jared Diamond not Joan Didion. Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom instead of John Fante. Wolfe’s A Man in Full instead of Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. Whatever, the pleasure’s in the dig, not the bones.

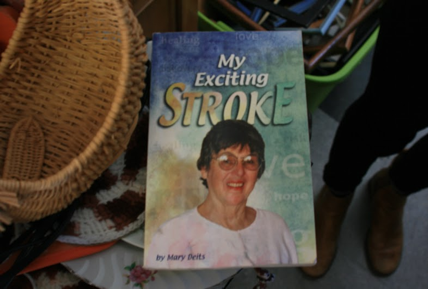

In the meantime, picking through the midden, you learn a lot about a culture’s past consumption. There was once a movie named Armageddon that sold 20 million VHS tapes and took nine people to write. That’s cool. Sometimes the garbage yields up even more surprising gems, like this one, My Exciting Stroke, a worthy title, something I might have chosen for this essay. More often than not though you’re digging through the same books—the Twilights, 50 Shades, the Pattersons, the Cornwells. There are the familiar literary titles as well . . .

In fact, after several years of strenuous scientific research, or at least a casual tallying in my head, I’ve managed to isolate the top five most discarded literary titles, none of which I’ve read—certainly I haven’t had time to read them this past year. So, without further ado, in no particular order, I present to you: 1) Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom 2) Alice Sebold, The Lovely Bones 3) Robert James Waller, The Bridges of Madison County 4) John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil 5) All of William T. Vollmann.

I’m very tired of seeing these books. If you’ve been considering reading The Bridges of Madison County you will be doing the planet and myself a considerable favor if you head immediately to your local Goodwill and buy it used instead of new.

Or don’t. Do whatever you want because what’s really so surprising and comforting about all of this—even as everything appears to be constantly peaking, edging toward chaos, and infinite content—is that literature really is something sustainable. There is a future to the author’s artifact. The books I see every week, on the corner of the same shelf, untouched and gathering dust while another copy gets shelved beside it—they don’t go to waste.

More and more Goodwills have turned away from dumping their vampire sex novels into landfills. Now they’re sold to paper companies, who in turn recycle them—even Franzen’s “Great American Novel”—into toilet paper.

Rest assured, even if we’re reading less, our literature is sustainable. The work has not been in vain. I can only hope that, one day, I too might achieve such a level of literary success and live to see my own book turned into some ultra-soft three-ply TP with the cursive word AMOR stamped in baby blue across corrugated fabric, “Textured for extra grip!”

I’m sorry if you’ve read this far—I know you have more content to get to—but let me leave you with a further final thought. My hunch is that if the reading and writing of literature now seems more untenable than ever, that probably means we need it . . . #NowMoreThanEver.

So head to your local thrift store and snatch up some of these titles before a new generation of content gluts the shelves. If I have any optimism in me I’d say that, short of nuclear ruin or environmental meltdown, among all the frightening piles of offal we may have to sift through at the end of this brief and feckless Trump presidency, most offending surely will be the innumerable book titles dedicated to understanding the conditions that persuaded Americans to elect and keep drinking the degrading hogwash of a cruel and incompetent pussy-grubbing con man.