It’s not that hard to describe. “Grief is like a bomber circling round and dropping its bombs each time the circle brings it overhead” is C.S. Lewis’ evocation of it. At a time when we are all living with “disenfranchised grief” as a recent article has it, what can we learn from works of literature to deal with grief, both real and disenfranchised? At this moment, as the coronavirus death toll in the US is near 600,000, what would a syllabus for modern grieving look like? Are there things to read that can help us understand some of the major points of dealing with loss, ways to empathize with ourselves and others and ways to find meaning, one of the best means to coping with grief?

Personally, I lost my grandparents when I was 19, 23, 25, and 35, and though I missed them, and still miss them all the time, their loss was part of the normal order of things. They all lived to be over 80 and accomplished the things that were important to them. Having a miscarriage was an entirely different sort of grief. My body had failed me, not being up to the task of nurturing my child. It felt to me like I had been promised something, a baby, and then it was cruelly snatched away, expectation shattered. Then, there was a part of me that felt I should not be grieving so much—was I being melodramatic? I had a wonderful, healthy two-year-old and I was only thirty—there was no physical reason I couldn’t eventually have more children. Those consolations did not change the fact that I felt intensely full of sorrow, cried all the time, and hated having a body that looked pregnant when it held a baby whose heartbeat had stopped. Perhaps those were the hardest days, between getting the news that I did not have a viable living fetus, walking around appearing four months pregnant while knowing I was not, and waiting for the procedure at the university hospital distant from my home that would remove the lifeless fetus from inside me.

A few months after my miscarriage we were walking around Franklin Street in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, the same town where my dilation and evacuation was done; it seemed like every woman we saw was pregnant and every other group we passed was pushing a baby carriage. It was too much for me—I told my husband to continue walking around with our daughter and fled up some steps to a second-floor used book store where I found things to read that would salve my sense of stabbing pain that it seemed like everyone else had something I could not have.

Retreating up the stairs to the haven of the printed word was natural for me—I had just finished a PhD in comparative literature and had always had the feeling, in the words of Cynthia Ozick’s character Puttermesser, “Puttermesser reads and reads. And if she does not know what it is she wants to know, she has only to read on.” Books always held answers. Even just the ability to distract me temporarily from my sadness, if not to ameliorate it, was useful.

A few years after my miscarriage, I came across a collection called, About What Was Lost: Twenty Writers on Miscarriage, Healing, and Hope at a bookstore in Northampton, MA, where I was living at the time. Now, looking it up to get the link, Amazon offers me over 25 different books on the topic. Though I could have searched at a library, the internet was not available to me in the same way it is now to find what will help at any moment. In fact, until I saw the book in the store, over seven years after my miscarriage and after I’d had two more children, I did not even think that I was missing the stories of others. It was such a relief to read it—this was a necessary book I would have dreamed of had I known it existed.

I felt impelled to review it and share with others; a discussion of it is one of my first published book reviews. I quoted the words of New York Times Magazine writer Emily Bazelon, who wisely discusses others helping her to “take my grief seriously,” and Slate reporter Dahlia Lithwick who notes that there are “no scripts” for dealing with miscarriage. The notion that others are feeling what I felt, that my grief was not melodrama or overreaction, but very much how many others who had experienced this type of loss and understood and processed the experience, made me feel much less alone.

Even just the ability to distract me temporarily from my sadness, if not to ameliorate it, was useful.Other books that deal with grief should ideally do for the reader what this one did for me, still coping with the aftereffects of loss even years later by allowing one to process and refine and think about one’s grief in the hope not of ameliorating it but of recognizing the role it needs to play in one’s life, how others dealt with similar or even more difficult situations.

Following is a brief, idiosyncratic, and necessarily incomplete list of some books about grief in the hopes that others, in reading, will be able to find some sense of consolation.

*

C.S Lewis, A Grief Observed (Faber and Faber)

Originally published under a pseudonym, Lewis’ 1961 classic contains the writer and scholar’s feelings about the passing of his 45-year-old wife, Joy Davidman, after they had been married just four years, a relationship dramatized in the 1993 movie Shadowlands with Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger. As Madeline L’Engle says in her introduction, “I am grateful, too, to Lewis for having the courage to yell, to doubt, to kick at God with angry violence. This is a part of healthy grief not often encouraged.” His descriptions of grief are apt: “I see the rowan berries reddening, and don’t know for a moment why they of all things, should be depressing. I hear a clock strike and some quality it always had before has gone out of the sound. What’s wrong with the world to make it so flat, shabby, worn-out looking? Then I remember.” The book is not only an evocation of Lewis’ feelings of intense grief but also his need to fold the tragedy of finding love and losing it quickly into his existing Christian faith.

Rabbi Harold Kushner, When Bad Things Happen to Good People (Schocken Books)

Another writer who is excellent at evoking personal grief and coping with it on a religious level is Rabbi Harold Kushner. His 1981 book was written after the death of his son Aaron at 14 from progeria, a disease of rapid aging. Kushner speaks not only of the challenges to his own faith from this untimely and tragic death, but of the struggles of others he has encountered in his rabbinate as well. Kushner speaks like a wise person with common sense who has undergone his own struggles and thus has the credibility to opine that others not similarly situated would not. A sampling of his sensibilities: “Whenever bad things happen to good people, there is likely to be the feeling that we might have prevented the misfortune if we had acted differently. And there will also certainly be feelings of anger. It seems to be instinctive to become angry when we are hurt. …

One of the most important questions when we are hurt and angry is, what do we do with our anger?” Kushner replies, in part, “The goal if we can achieve it, would be to be angry at the situation … recognizing it as something rotten, unfair, and totally undeserved, shouting about it, denouncing it, crying over it, permits us to discharge the anger which is a part of being hurt, without making it harder for us to be helped.” Compassion and a realistic approach to emotions around difficult situations enable this book to provide much needed solace to any one who seeks it.

Gail Godwin, Grief Cottage (Bloomsbury)

Fiction about grief is a way of getting at the issue but maybe at a mediated distance; the inventive nature of it allows one to travel to new places and get new perspectives even on the same pesky and difficult matters. One of my favorite writers, Gail Godwin, authored a 2017 novel, Grief Cottage, about a pre-teen boy whose single mother is killed unexpectedly in a car accident, which necessitates his going to live with his great aunt, an artist who lives a hermetic life on a South Carolina island. Before she dies, Marcus’ mother tells him, “Isn’t it wonderful what art can do, Marcus? It was so sad, I saw my life in every line, but at the same time it made me feel part of the human family—it made me feel so alive.”

Over the course of the novel, the young Marcus encounters a ghost and matures, after some struggle, into a doctor who meets and makes amends with the family of the father he never knew, as well as learning to cope with his own disenfranchised grief. Godwin’s wisdom and awareness of how art is part of a healing process, as well as the chance to follow along with the habits and mating progress of the endangered sea turtles on this island, make her novel a must-read.

Joan Silber, Secrets of Happiness (Counterpoint)

There are many deaths in Secrets of Happiness, and some of the multiple plot lines—about seemingly disparate characters who end up being connected in a variety of ways—are about the healthy and less healthy ways that characters cope with loss. One plot line involves a gay couple, one of whom gets sick, which precipitates a breakup after 20 years; the new lover of his former partner helps care for him and has a dream about him after his passing where he says, “People listen to me now.” The same grieving character says, “Everyone wanted me back the way I was. Which was not what even I wanted.” The matter-of-factness about the difficulty of grieving, even those we are loosely connected to, plus the ability fiction gives us to see how others cope and grieve to be aware of “the truth of impermanence” as Silber writes, makes this novel a useful addition to the syllabus.

Sigrid Nunez, The Friend and What Are You Going Through (Riverhead)

Sigrid Nunez’s two most recent novels The Friend (2018) and What Are You Going Through (2020) concern those both contemplating death (the latter) and coping with loss (the former). Nunez has said that she was moved by stories of animals grieving for their owners when she made a Great Dane whose owner has committed suicide a protagonist of The Friend. Not a gimmick, but a vehicle. Read to receive such wisdom as the words a veterinarian tells the new owner of the grieving dog, “He may never recover, no matter what you do. And you’ll never know why. It’s not just that you don’t know his history. People think dogs are simple, and we like to believe we know what goes on in their heads. But in fact we’re finding out that dogs are a lot more mysterious and complicated than we ever thought, and unless they develop our language we’ll never know them, at all.”

I have written elsewhere about What Are You Going Through, whose plot is about a woman dying of cancer who enlists her former roommate to help her end her life when she decides it is time—in Nunez’s words, “Lucy and Ethel do euthanasia.” The narrator develops a closeness to her friend that she has not felt with another person, yet the novel remains clear-eyed, never maudlin. The woman who has cancer tells a social worker, “The meaning of life is that it stops. Of course it would have been a writer who came up with the answer. Of course that writer would have been Kafka.” If these words are comforting to you, read on.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Notes on Grief (Knopf)

Memoirs of grief both memorialize the one who has passed and discuss the impact of this loss on those who remain. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie discusses the passing of her father in her recent Notes on Grief. Adichie writes of the process from learning of her father’s passing, unexpectedly quickly from kidney failure, to her last sentence, where she states that she is writing about her father in the past tense though she cannot believe it is past tense. Of her experience, she says, “We don’t know how we will grieve until we grieve” and continues later, “The need to proclaim not merely the loss but the love, the continuity. I am my father’s daughter. It is an act of resistance and refusal: grief telling you it is over and your heart saying it is not; grief trying to shrink your love to the past and your heart saying it is present.”

Sherri Mandell, Reaching for Comfort: What I Saw, What I Learned, and How I Blew it Training as a Pastoral Counselor (Ben Yehuda Press)

Grief and its coping mechanisms are as individual as loss. A new memoir by Sherri Mandell (she has published two others, one which won a National Jewish Book Award) discusses her personal search for an end to the suffering she has undergone after her 13-year-old son’s murder. This one is not about the brave public face she puts on in her first memoir, The Blessing of a Broken Heart, about how “my husband and I were able to take the cruelty of our son’s murder and turn it into kindness through the work of the Koby Mandell Foundation.” Mandell discusses speaking around the world and having the memoir turned into a play, then adds, “But that was the public me, the one on the stage. The one who was frantic to prove that she was okay. The one who spoke and wrote in a voice of triumph. The private me was different. The private me longed for comfort. And I knew it wasn’t going to be easy to find.”

So begins her lovely new memoir Reaching for Comfort: “I hoped that I would meet a guide there who would reveal to me the secret of how to emerge from the darkness. I know she or he could be anywhere: a patient , worker, visitor, doctor or a fellow student. … I imagined that this guide would tell me something so profound that all at once, everything would change. I would stop looking into the darkness for sustenance. I would leave death behind and once again I would take pleasure in the light and the fresh air.” The journey is not so simple and she does not find one guide, but she does learn from her encounters with others. This book is a powerful reminder of the value of connecting with others and using your own pain to enable others to cope with theirs.

*

After I had a miscarriage and before I found an anthology about it, one thing helped me. A woman at my synagogue who was in her eighties (whose children were in their fifties or sixties and were grandparents themselves) came up to me one Saturday to tell me about her own miscarriage. She teared up telling me about the experience, though a quick calculation led me to believe it had to have occurred over 50 years ago; speaking about it, her grief became fresh once again. I thought then, It is okay to feel this way. My grief is real and reasonable. No one else in my life had allowed me to feel that, to know that grief is something that remains a presence even when other things come to replace it. If you don’t have anyone in your life to affirm your grief over a mortal loss or over the loss of all the gatherings and activities that you have not had for the past 15 months of this pandemic, books will allow you know that you don’t have to grieve alone. They won’t solve problems, but they will give a reader the knowledge that others are sharing your experience. That can enable even the most grief-stricken among us to understand we are less alone than we thought we were.

*

Extra Credit Reading:

Ariel Burger, Witness: Lessons from Elie Wiesel’s Clasroom (Mariner Books)

Witness is a memoir of Burger’s time as a teaching assistant for the late Elie Wiesel, in the final years that Wiesel taught at Boston University, where he was on faculty 1976-2013. Burger discusses some of the many texts that Holocaust survivor and Jewish scholar Wiesel used to answer his own questions about the world and the nature of suffering, how Wiesel responded to the many difficult situations his students found themselves in, and how he interpreted the diverse books on his syllabi. A reading list is at the back.

Yaa Gyasi, Transcendent Kingdom (Knopf)

Transcendent Kingdom is a novel-length meditation on grief, as the protagonist and her mother mourn the promising brother and son, a talented athlete who became addicted to the painkillers that led to his death after an injury in a basketball game. The protagonist becomes a neurologist who researches how mice, and by extension humans, respond to pain. She sums her work up as thus: “I try to make order, make sense, make meaning of the jumble of it all.”

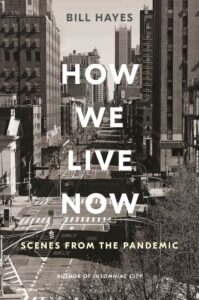

Bill Hayes, How We Live Now: Scenes from the Pandemic (Bloomsbury)

This is one the first wave of books that will undoubtedly recount the experience of living through the pandemic, published in August 2020. What makes this worth having is the photos of an empty New York City by the author who is a professional photographer, as well as his observations including those of his late partner, doctor and writer Oliver Sacks, like this one: “The most we can do is write—intelligently, creatively, critically, evocatively—about what it is like living in the world at this time.”