Writerly Lessons From an Early '90s Improv Class

Joanna Hershon on What Theater Taught Her About Scene,

Character, and Rejection

Between the ages of eight and twenty-five, I couldn’t imagine my life free of the burning desire to either be onstage or in some dark rehearsal space preparing to be. I’d been a passionate devotee of the craft since the summer of fourth grade, when a man named Tony with tortoise shell glasses and broad shoulders showed my ballet class how to create something called a Living Sound Machine. After laying on the dusty floor with my head resting on another girl’s stomach and making intuitive noises, it was bye bye pirouettes and hello inhabiting the body. Stage combat. Monologues. My ninth grade English teacher calling me Sarah (as in Bernhardt), etcetera.

The desire to be cast, to be chosen—this sensation went from a thrilling notion to a total curse. Somewhere in the middle, I went to acting school in London.

It was the early 1990s; there was an economic recession and rain and these amazing oat cakes and milky sugary tea and I was 20 years old on a semester abroad. I’d attended any kind of theater program I could rope my parents into paying for throughout my young life. This one was the type of American university program that was so well-funded it attracted the city’s best teachers and actors, but pretty much anyone could attend just as long as they could pay.

I had a teacher named Clare, who favored turtlenecks and pendants and said things like, “Well of course my dear you are a Pinter Lady,” and, while teaching Uncle Vanya, showed the class how—with the simple act of wearing my hair at the base of my neck or on top of my head—I could be either a Sonya or a Yelena. Clare also taught an improvisation class outside the program. One day, in a hushed tone, she invited me and a few select others to attend.

Improvisation conjured comedy but this was not comedy. This was a windowless basement with Clare, dead serious. Clare, who created scenarios for small groups and conspired with each of us, separately, in the hallway, letting us know our specific secrets and desires. We were on a train, in a garden, in a mansion, a deserted car park. We were in debt, desperate for sex, massively in debt, pregnant. We had no idea what we would get from the other actors. No lines or anything was given aside from a setting and basic scenario and the secrets and desires whispered to us in the musty hallway by Clare.

I don’t remember exactly who was in the class but I have flashes of an older Turkish man who had a wife and child, an American named Jeremiah who was never not wearing an uncomfortable looking leather jacket that didn’t look broken-in despite being authentically vintage, and a British waif with cascading auburn hair who couldn’t be touched anywhere close to her ears or else she’d start hysterically crying. I can’t tell you specific scenes I acted in or the story lines I witnessed during those winter weeknights in Camden Town, but I remember the older Turkish man and the ginger-haired waif making out at the end of a scene and there were tears running down both of their faces.

I suppose I’m inevitably Clare at first, setting the parameters of place and time and choosing the secrets and desires, but then I’m each person in a scene.

The freewheeling sense of intensity between people, the sense that anything could happen remains a physical sense memory. It’s 25 years later and when I think about that room, it’s as pure a definition of drama as I can conjure. The term “drama” is derived from the ancient Greek word meaning “action,” which is derived from “I do.” In English and other Romance languages, the word for drama was “play” or “game” and the creator of the play was a “play-maker,” the building where the plays or games were performed, “play-houses.”

We’d emerge from Clare’s basement—our play-house—vibrating with life’s possibilities. We’d light up our cigarettes, and—breathing in the smoke and the brackish air from the canal—look up at the silver clouds in the starless sky, flirt on the way to the tube.

I spent so much of my youth focused on acting or—more accurately after graduating from college—doing the things one needs to do in order to possibly act: getting headshots taken and resumes printed, auditioning, looking for representation, schmoozing. This part of acting was (spoiler-alert!) a slog. Though I still loved the experience of being cast when it happened, of meeting new people and collaborating, the career part of the equation was not proving fruitful. And my relationship to performing began to change. I felt more reticent, somehow, more interior. I questioned the long-term effects of having to consider my looks for a living and became more self-conscious.

I’d also always written, and when (after plenty of hand-wringing) I officially called it quits in my mid-twenties and went to Columbia to earn an MFA in fiction, it was as if a fog had miraculously lifted and I wondered why I’d wasted so much time on such a narcissistic pursuit. It occurred to me that I considered the hours and hours of acting similar to how former addicts spoke of addiction. So much time and money and for what?

But then one day during the first semester of graduate school, while a fellow student was trying to work out a character issue, I asked what the character wanted. My classmate was confused at first and then found the question helpful. I realized I might have learned more from acting then I’d previously assumed. I’d taken for granted so much about the way my mind worked. Now that I was getting the chance to hear from other writers in an intimate environment, I was learning that not only were my strengths likely directly affected by my acting background, but that I might have something to offer if I tried to describe the process.

As I struggled to convey what I meant, I understood I was speaking a language so integral to how I approached storytelling that I hadn’t realized it came directly from assimilating hours of Method and Meisner and the other more esoteric offerings I’d absorbed over the years. When I sat down to write, it was as if—though I’d stopped trying to get hired as an actress—I was still in that basement in London.

And I still am. I suppose I’m inevitably Clare at first, setting the parameters of place and time and choosing the secrets and desires, but then I’m each person in a scene, determined to get what I want and need. But I’m also the other person. I play out both motivations, which are always, of course, in direct opposition. Show me a scene where two people want the same thing (unless maybe it’s the final scene of a book) and I’ll show you a scene that’s doomed.

I might have become a more interesting and informed person but it’s equally possible I could have become a less interesting one.

I no longer consider all those acting classes a waste of time. And being a failed (former!) actor is its own kind of club. While hiking in the woods recently, I met a woman who was so authentically outdoorsy it was difficult to even picture her in a city, but there was also something about her bearing that struck me as familiar. When I later learned that she’d not only been a musical theater major but had starred in the company tour of Les Miserables, I was almost unsurprised. I once saw a dermatologist who was so composed and wryly funny that I found myself asking if he’d ever considered acting; we ended up trading audition horror stories.

Maybe the secret club of former actors is also about sharing a quality that comes from artistic training but perhaps just as deeply from having put oneself in the position of being rejected countless times and still having managed—at least during some point during the process—to feel free. We might roll our eyes and refer to our failed acting careers but we also remember that feeling.

I do wonder what would have happened if I’d stopped acting after middle school or high school, if I’d gone to Africa or Mexico or Morocco instead of London, if I’d expanded my views in an altogether different way. I might have become a more interesting and informed person but it’s equally possible I could have become a less interesting one. Or I might have ended up with equal skills and empathy, with a different frame of reference.

I’ve thought about acting, in the years since I left it behind, in many ways: as deep engagement with humanity and storytelling, as a frivolous, egotistic pursuit, as life-affirming and fun. But mostly I think of it as a teacher. It taught me how to listen, how to pay close attention to myself and to others, how to handle being watched and judged, how to forget being watched and judged. Approaching situations from the inside out, paying specific attention—it all now strikes me as sound preparation for life.

__________________________________

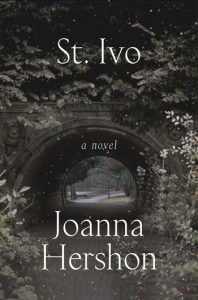

Joanna Hershon’s novel St. Ivo is available from FSG.

Joanna Hershon

Joanna Hershon is the author of the novels Swimming, The Outside of August, The German Bride, and A Dual Inheritance. Her writing has appeared in Granta, The New York Times, One Story, Virginia Quarterly Review, and two literary anthologies, Brooklyn Was Mine and Freud’s Blind Spot. She is an adjunct assistant professor in the Creative Writing Department at Columbia University and lives in Brooklyn with her husband, the painter Derek Buckner, their twin sons, and their daughter.