Writer Erika Krouse On Her Time As A Private Investigator

“Many people were willing to open up to me, even when doing so meant danger to them and their lives.”

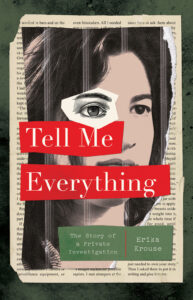

Erika Krouse has a superpower—she has the kind of face that makes people tell her anything and everything, a face that got her hired as a private detective. Her time as a PI is the subject of her new memoir, Tell Me Everything, now available from Flatiron Publishing, in which Krouse details the difficult, all-consuming case she worked involved rape culture and football recruiters at a prominent university. Interspersed are snapshots of Krouse’s life, exploring the lingering effects of childhood trauma upon her psyche. Erika Krouse was kind enough to answer a few questions over email about her new book and the stranger-than-fiction story behind it.

*

Molly Odintz: So, you have the kind of face that makes people want to tell you their deepest, darkest secrets. What does that mean for daily life?

Erika Krouse: I have no idea! It’s been that way for a long time, so I don’t know a different way of relating to people. But I do know I’m not alone in this; many writers have that kind of face, as do reporters, PIs, and others. It seems like the people I meet are always hopscotching back and forth between self-disguise and confession. It’s made me realize how much people long to be known and seen—how unbearable it is for most people to carry a secret alone, without sharing it.

MO: How did you get into private investigation work?

EK: I was in a bookstore and a lawyer I didn’t know started telling me about his private life. After a moment, he stopped, shocked at himself for telling a complete stranger so much. When I told him that this happened to me all the time, he hired me on the spot as a PI. I had no experience, no idea how to do the job. But for some unknown reason, he had faith in me, and he gave me these huge assignments that changed my life.

MO: Can you tell us a bit about the university case your book revolves around? How did your special talents contribute to cracking the case?

EK: In 2001, a female college student was sexually assaulted by a group of college football players and recruits, as part of a recruiting campus visit designed to entice the recruits to attend the school. “Grayson,” my lawyer-boss, believed the university was contributing to a rape culture that endangered women, and that the case could be tried under Title IX discrimination. This was the first Title IX sexual assault case in history—before this point, Title IX was just about facilities and money. So we were trodding new legal ground in a David-and-Goliath case, a career case with high stakes.

My job was to gather evidence, to draw out witnesses and try to get them to trust me enough to tell me their stories. I talked to survivors, college football players, trainers, witnesses, employees, cheerleaders, and even sex workers who were hired to service the recruits and players. The victim count ballooned, and the case became enormous. Many people were willing to open up to me, even when doing so meant danger to them and their lives. They wanted a change, or they wanted to prevent change. Both kinds of conversations were equally revealing.

MO: You write in your memoir that your ability to read others and appear open and empathetic to them stems from the trauma of your own childhood. What is the relationship between trauma and quickly reading situations and people?

EK: Trauma is usually entwined with secrecy. If bad things happen to you, you often learn how to hide the damage so you can pretend to function in ordinary life. So it’s a bit like the phrase, “You can’t kid a kidder”; it’s easy to recognize deception when you practice it all the time. You know the tricks. And if you know when a person is lying, you can usually guess what the lie is about, or what motivates it.

Trauma also makes most of us hypervigilant, with a heightened fight/flight/freeze instinct. We know when something’s up, because detecting change can mean the difference between survival and danger. We recognize clues because we feel more than other people, or less, or differently. We’re less likely to cling to social conventions, or dismiss something fishy. We snag on exceptions.

MO: This is one of the more unusual stories of PI work I’ve come across. What surprised you the most about PI work, compared to your expectations?

EK: Thank you! I think what surprised me most was that I loved it so much. And it’s not at all like the fiction I had read; I couldn’t do anything illegal (carry a gun, hit people) without going to jail like anyone else. Because I wasn’t a cop or a lawyer, people had no real reason to talk to me, and I had no way to demand information from them. It was all voluntary, information bought with free beer and nachos, which made it even more exciting when it worked. I got to see people at their best, people who were helping the case just because they could, and because what had happened was wrong. I also saw people at their worst, people who didn’t care about anyone or anything but themselves.

MO: How did writing a memoir compare to writing fiction?

EK: It was harder and easier. The easy part was the story—I didn’t have to invent anything. But emotionally, it was the most difficult thing I’ve ever written. I had never really written about myself before, except in that coded way that fiction writers do. Sometimes I had to write this memoir blindly, with my head down on my desk and my eyes closed. I also felt more fragile during the feedback process, because the person there on the page was me, vulnerable. But the biggest difference was in the editing stage, because with nonfiction, you can inadvertently hurt someone. I had night terrors, wondering if I had failed to disguise a survivor in a particular way.

MO: What’s your advice to the gumshoe or writer who’s just starting out?

EK: A requirement of both jobs is that you pay attention to the things other people miss. It’s all about understanding individuals—how they work, what they do, how they remember, what values or fears guide them. You’re trying to excavate the past, so it helps to try to understand how people combine and distort each other so those events happened in the first place. Every crime is a unique and complex system, as is every book, as is every person. So if you can begin to understand that system, you know what to look for and draw out. It helps to remember that both professions are arts, not sciences. You discover a crime or a book from the inside out, and also from the outside in. That’s why they go together so well, crime and books. It’s a perfect pairing.

__________________________________

Erika Krouse’s Tell Me Everything is out now from Flatiron Books.

Molly Odintz

Molly Odintz is the managing editor for CrimeReads and the editor of Austin Noir, now available from Akashic Books. She grew up in Austin and worked as a bookseller before becoming a Very Professional Internet Person. She lives in central Texas with her cat, Fritz Lang.