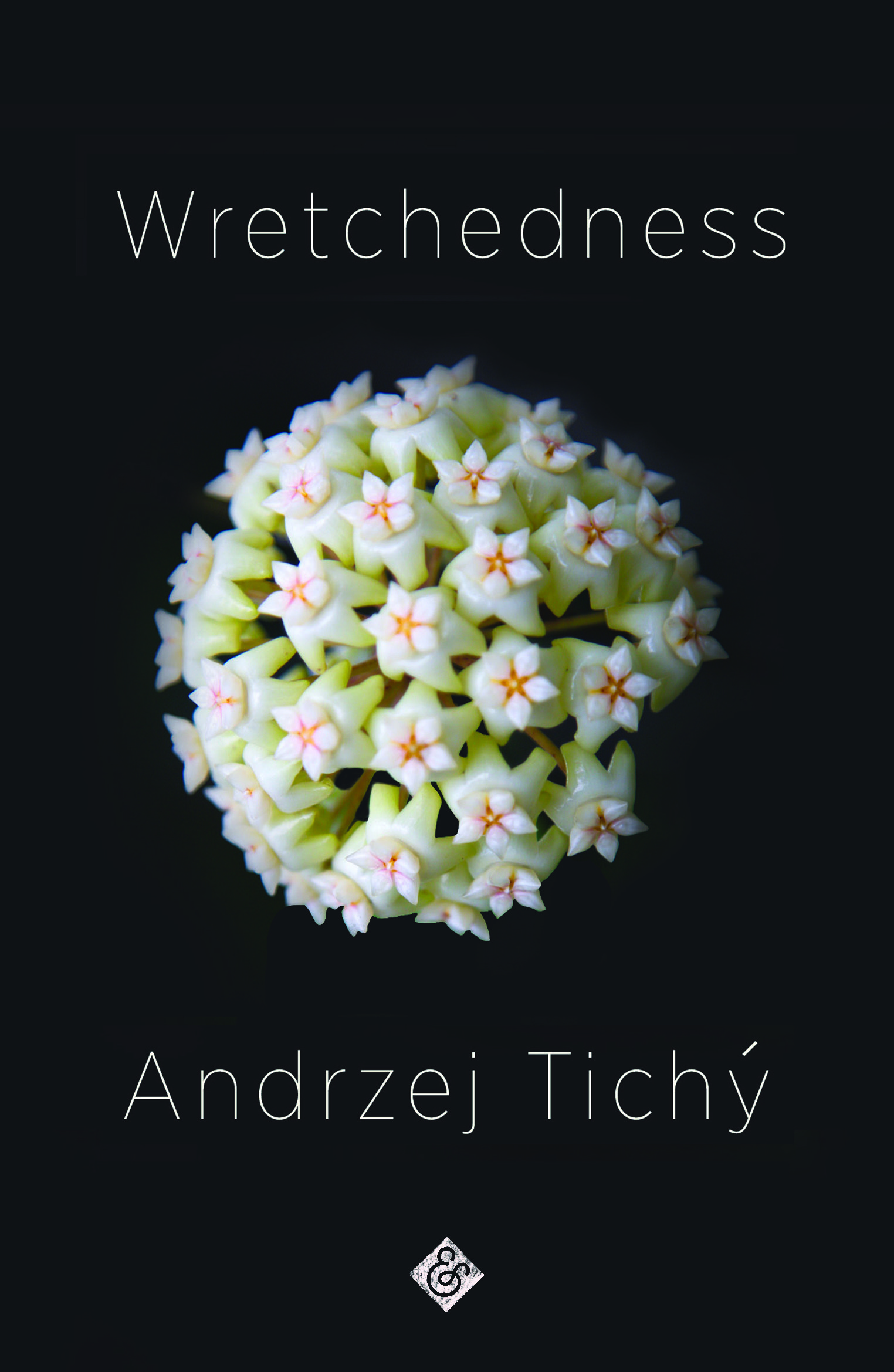

The whole morning, while practicing a Scelsi piece – his Fourth String Quartet, to be precise – I kept glancing at the wax-plant flowers that had opened during the night. The white and pink blossoms hung in clusters and looked like tiny little eyes watching over me: a little audience from another species, I thought afterwards, in the afternoon, as I stood by the canal, by the gravel path between the police station and the water, and waited for the guitarist and the composer. I was meant to be going to Copenhagen with them to hear a concert by the German organist Christoph Maria Moosmann at the cathedral, Vor Frue Kirke. Moosmann would be playing pieces by Pärt and Cage, and In Nomine Lucis, by Scelsi himself, a piece that sounded absolutely magnificent on a church organ, I knew that from experience because I’d heard Kevin Bowyer play it, it was quite clearly in the same class – as I asserted then, at least – as the best works for organ by Messiaen and Bach. But that morning I didn’t give any of that a thought. As with all successful rehearsals, I was completely reset, emptied of words and concepts, free of thoughts, memories and desires, and yet in the grip of some centripetal motion, on the way to something significant. I looked at the sheet music in front of me and breathed. My ribcage, my lungs and my arms were moving. My elbows were moving, and my fingers. Sound became flesh, body. I closed my eyes and was no longer myself. Now we were approaching the central station, and the guitarist said something about the time, presumably because he’d caught sight of the clock up on the tower. He said we had plenty of time after all, assuming the train wasn’t delayed, and I said it was probably going to be fine, at the same time as I thought I should ask the composer to repeat what she’d said a minute ago, about geometry, and that I wanted to tell them about Scelsi’s Fourth String Quartet, which, I was pretty sure, neither the guitarist nor the composer were that closely acquainted with. The most interesting thing, I wanted to say, was, aside from many things I’d like to come back to (for instance its scordatura and the relationship with the golden ratio), the notation. The piece was written in such a way that every string had its own stave in the score, as though it were composed for sixteen instruments, rather than the quartet’s four, and as though I, normally responsible for one instrument, with a relatively broad register, was now playing four instruments, which independently, and viewed as instruments, were poorer in terms of expression and tone, but which, in some way, and this was what I wanted to discuss with the guitarist and the composer, together succeeded in constituting something that was different, that was more than a cello, and which, assuming the same was the case for the quartet’s other instruments, meant we were something other than a string quartet. But what? And why? And how did that fit with the character of the piece, that striving, ascending, descending, trembling, like a tug-of-war between weight and levity, between descent and ascent? Playing it felt, on the whole, like falling upwards. Does that sound feasible? I wanted to ask the composer. What was it she’d said about geometry? I hadn’t been able to make out her words, I’d been thinking about Soot instead, as though he was standing before me, swaying just above me, in a kind of formless guise, unfathomable, an invisible light, and hearing him say, voicelessly, yes, soundlessly: so I don’t know, Cody. Why? A soldier dies, gets shot down. Nothing so strange about that, is there? That’s what they do, soldiers. They die, fall, drop their guns, someone captures them in that moment, on film, mid-fall, falling, in the air. Someone takes a picture, it gets turned into a banner, makes its way around the world. Then we’re sitting there, a bunch of years later, under that picture, and Denzo digs out a bit of standard and roasts the tobacco and you start thinking finally a little peace and quiet, finally a little respite, as they say, finally respectus, refugium, sanctum, the kind of stuff the coconuts come out with, and you know my dad told me this is paradise, and thirty years later he’d acknowledge that the whole thing had been a bluff, a lie, that he regretted the whole move, the emigration, as he put it, the emigration, cos, you know, he was never an immigrant in his own mind, no fucking immigrant, he was an emigrant, man, an exile, brah, and he said he regretted all his thirty years in exile, he was sorry for it, you know, wanted to ask forgiveness for everything then, when it was already too late, but you know, we were just sitting there under the banner with the dying soldier and we carefully sent round the bong, and I puked later, again, as per, with Denzo, that was his name, he was the one, but why? we laughed, do you remember? Metallica’s double basses, some cripple in a video, ah, I don’t know, there’s no justice, I cannot live, I cannot die, trapped in myself, absolute horror, and Mum watching Oprah, watching The Bold and the Beautiful, and you know, did you know Olga moved back to Kazakhstan, but you know, soon she fell over the Russian border, started streetwalking, as they say, in Novokuznetsk, started shooting up speed and horse, I know this cos I spoke to her two months after she’d gone, but then it went quiet and there were rumors she’d started using krokodil, and in that case they’ll be burying the rest of her worn-out body soon enough, but I mean, I swear, you know that guy Anden, the guy who was playing the big man in the yard, when we fought I called him a nigger and he called me a cunt or a queer, that’s what we used to say when we were kids, but it’s not him, and it’s not Denzo, not him, I think he’s alive, and it’s not Niko, we called him Niko, his name was Niklas, and he died, he died – what – ten, is it already ten years ago, he died in front of the TV, his mum found him, did you know that? Died in front of the TV, heart stopped beating or something, stopped breathing, suffocated by his own vomit, I don’t know what happens when you shoot too much horse, but his mum found him in front of the TV, dead, overdose, and I always think about TV static and about his mum coming into the room and seeing her son is dead, this guy, you know, who I used to play with once, and I mean you can ask yourself why here, you get me, he was no soldier, or OK, maybe he was, I mean, what is a war? I guess it’s about finding the biggest gang. Arben preferred to head over to Kosovo rather than stay here with his anxiety, if you remember, and at the time we thought how the fuck can he do that? But today it’s totally obvious, why shouldn’t he go over there? And today they go to new places, where the biggest gangs are, the ones open to them in any case, I mean they could hardly join the cops or the military, too late for that, but I don’t know, what do I know, this has nothing to do with Niko either, he was just a regular junkie, and I don’t know why I thought of the TV static either, if he was watching TV it was probably playing, just cos he died it didn’t make the TV stop, I mean everything goes on I guess, life goes on, the TV goes on, the ads go on, the news goes on, the series, the films, the chat shows, the comedies, the thrillers, the tear-jerkers, the cop shows, and at some point his mum came into the room and saw her kid as a corpse, and so she lifted up his head, and you know how heavy and cold a dead head is, it weighs a fucking ton, mate, and she hit him over the head and over the chest and jerked her kid about, pulling at this corpse, trying and failing to shake some life into her kid, his life was gone, it was over, she’d seen it come and go, once he didn’t exist, then he did, and now he didn’t again, just as all other life was continuing, and that bit is hard to get your head around. . . .

. . . . Back then we were brothers, right, bratku, punks and hard rockers, brats, kids, snotty little kids with fags and hash and marker pens in bumbags, we ran around at night with butterfly knives and stilettos, Reeperbahn, Altona, Karoviertel, right digga, broke into places, stole, when we were little, went to gigs at Die Fabrik, Docks, Große Freiheit, Markthalle, Störtebeker, saw Fugazi, Cypress Hill, Sick of It All, Strife, Unsane, moshed stoned in sweat, blood and spit, adrenalin-racing little animals, that whole white-trash thing, fucking hostile, bumfluffed little boys, steeped in that American shit, and we watched the films, looked at the records, slammed here and pogoed there, just another victim, kid, with our bloody noses clotting, but whose blood is that, kid? Isn’t that what you say, Cody? Sat up late at night watching video after video, Suicidal Tendencies and War Inside My Head, but also Psí Vojáci, the dog soldiers, and later on their song about razor blades too, razor blades on the body, razor blades in the body, and our dads who’d both cut their arms, such brothers, and his mum who said she’d heard it was the sweetest thing, when your body drains of blood, when the life runs out, better than the best drugs, better than crack, better than a speedball, but what happens? we asked, it’s like you rise and sink at the same time, and we creased up, we laughed, drank powdered ice tea and went on little trips to the sea, I remember that guy who’d never seen the sea, went to Heligoland, stole little bottles of spirits in the shop and hid in a cubbyhole under a stairwell on the ferry, down it, neck it, creasing up like idiots, Sweden doesn’t exist, Denmark’s going under, Germany we love you, Yugoslavia’s burning, Europe is the future, the Eastern European kids fuck themselves in the arse with turquoise double-enders, their tender, oozing dreams flowing like pure shit, what’s happening, man, how hard can life be, really, if we’re honest, and how tender is it to die by your own hand, just how, how focused do you have to be, yeah, yeah, it was screwed up, and being screwed up was something to aspire to, so we fucked off down to Bambule, floated about between the scabby caravans, the mud, the planks, the rubbish, the smoke and the fires in big rusty barrels, in shopping trolleys, the rags, fighting words, flags, it was anarchy for idiots, we said to each other.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Wretchedness by Andrzej Tichý, translated by Nichola Smalley. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, And Other Stories.