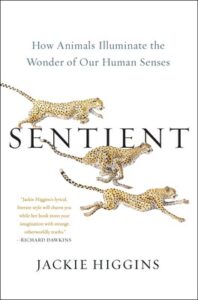

Worlds Unseen and Unimagined: On Learning About Human Senses Through the Animal Kingdom

Jackie Higgins Considers the Abundance of Biodiversity All Around Us

In his essay “Possible Worlds,” John Burdon Sanderson (known as J.B.S. or Jack) Haldane declared, “My own suspicion is that the Universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose. I suspect there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of, or can be dreamed of, in any philosophy.” These words are often quoted with a glance to the stars and imaginations spiraling toward the possibility of others worlds beyond our planet.

However, recently while researching my book Sentient: How Animals Illuminate the Wonders of Our Human Senses, I was reminded of their earthbound interpretation. With a characteristic sense of mischief, Haldane decided on the barnacle as his subject of enquiry and asked, “How does the world appear to a being with different senses and instinct from our own?”

My book considers how the world might look to a mantis shrimp or a deep-sea spookfish; how owls see their surroundings through sound, bloodhounds through smell and star-nosed moles through touch. These animals afford us a better understanding of how our own senses work, both those we recognize and those we don’t. They expose the Greek myth that started with Aristotle and hint at the diversity of human experience. We meet the woman who had no idea that she saw millions more colors than most and the man who lost a sense he didn’t even know he had (sense of body) with catastrophic consequence.

Ultimately, these creatures remind us of the fundamental importance of Haldane’s observation; the existence of their many possible worlds is proof that our own human view of reality is neither true nor complete.

Nature boasts sensory powers that extend far beyond the obvious.

The first challenge I faced when writing Sentient was to select a cast of creatures to represent our different human senses. The entire animal kingdom was at my disposal: the one million, or so, known species along with the thousands of new ones discovered every year. My task appeared Herculean. To narrow the field, I began a deep trawl through academic literature, in search of those creatures whose sensory systems had attracted scientific scrutiny and could shed light on our own capabilities.

We assume that what we sense represents the limits of the world. Take what we see, we rely overwhelmingly on our color vision. We may revel in the spectacular rainbow displays of a male peacock’s plumage or an Australian giant cuttlefish’s shade-shifting mantle, forgetful of the fact that our eyes detect only a slither of the available electromagnetic spectrum. The amount of information within light is diverse, possibly infinite. Birds see wavelengths that are invisible to our eyes, so do bees and butterflies; to them, peacock feathers quiver in multi-colored and ultraviolet hues. The cuttlefish might be color blind in the traditional sense but can still distinguish between the many shades of the rainbow.

Furthermore, because this creature is sensitive to the way in which light is polarized, it accesses an entirely new visual dimension: a secret language of light. The ogre-faced spider demonstrates another skill. It can eke out photons, even on nights without moon or stars. Suspended in vegetation, it stretches a sticky, silken net between its front legs. Two of its eight eyes are so enormous—the largest of any arachnid—they can make out tiny movements in the gloom. This enables the spider to lunge with ballistic speed and precision, to ensnare its next meal.

The pit viper’s ability to strike at mice in the pitch dark is widely attributed to infra-red “vision,” but in actuality this sense is an unusual form of touch that takes place without any physical contact. Today, “touch” is an umbrella term for many separate somatic senses. “Discriminative touch” describes how our fingertips discern the corrugated roughness of a walnut or the smoothness of a ball bearing; how a boa constrictor knows when to relax its deadly embrace, feeling its victim’s fading pulse. In contrast, the viper uses a sense of touch called “thermoception” to register the infra-red aura radiating from its warm-blooded prey.

Recently, scientists found that the heat-sensing molecules in the snake’s pit organs are much like ones that are present in our skin. These enable us to experience the warmth of human contact; those of the snake are so sensitive, they detect the heat of a mouse up to one meter away. There is a further variant of touch. The naked mole rat may survive without oxygen for some eighteen minutes, resist aging and cancer, but most notably it is impervious to certain types of pain. Humans smart when our skin is rubbed with chili or acid, but this buck-toothed, boss-eyed rodent feels nothing. Pain serves a clear purpose, warning of often invisible dangers; it is our guardian angel.

Scientists are undecided as to why this sense is diminished in the naked mole rat. Perhaps it is because the atmosphere in their burrows is so acrid. Or, because they are share their home with an aggressive and venomous species of ant. Either way, this creature provides inspiration and clues that may well lead to a remedy for human pain.

What is true of vision and touch also applies across our other senses. The natural world is clamorous with sounds that we cannot hear because our ears detect only a narrow band of frequencies. We are deaf to the low infrasound of elephants communicating across the African plains and to the infrasonic rumbles within a tiger’s roar. On a balmy summer evening, we are oblivious to an ultrasonic battle taking place above our heads. Bats deploy high-frequency sonar to chase tiger moths on the wing, but their system can be jammed, either a competitor swooping in to steal the prize or the insect retaliating to defend itself. The echolocation of the greater bulldog bat is so precise that, as it skims over a pond, from thirteen meters away, it can detect the tell-tale ripple of a fish beneath the surface.

Yet none of these auditory experts can compete with one unusual Chinese amphibian. The concave-eared torrent frog gathers at the foot of thunderous waterfalls. To serenade potential mates through the din, it issues ultrasonic notes. However, its audience is not always tuned to these seductive frequencies. In much the same way as we dial into a radio station, this tiny frog adjusts its audible bandwidth. It is the only known species to select what it can hear.

The animal kingdom is suffused with odors; some alluring, some odious, others we cannot smell, yet may still sway us subliminally. Not all noses are created equal. A polar bear can pick up the scent of a seal’s breathing hole from some three kilometers. On moonless nights, an Asian ailanthus silkmoth raises its antennae to the air currents and uses the same sense to find a female five kilometers away. Much as noses are not necessary for smell, nor are tongues for taste. Blowflies taste through their feet and a fish called the sea-robin does so through its fins. Meanwhile, a snake flicks its forked tongue to sample scents on the air. To blur divisions further between the organs of taste and smell, scientists have found that our tongue can detect odors and our nose is scattered with taste-like cells.

Nature boasts sensory powers that extend far beyond the obvious. Monarch butterflies can sense the earth’s magnetic field, enabling them to navigate an annual pilgrimage from Canada to Mexico, and back again. Rufous hummingbirds can sense the time of day. When a great white shark attacks, it rolls back its eyeballs and relies on its ability to sense the electric field of its victim. The Skywalker hoolock gibbon, only discovered in 2017, leaps and swings through the towering trees of the Gaoligong Forest, saved from falls by sharpened senses of body, movement and balance.

As the late, great naturalist E.O. Wilson asserted, biologically speaking, earth remains “a mostly unexplored planet.” Despite my training as a zoologist, followed by decades making natural history and science documentaries, I was mesmerized by the abundance of biodiversity that I encountered when researching this book. The truth is, I was spoilt for choice. Sentient showcases a whole different cast of creatures whose senses reveal the many worlds within our own.

____________________________________________________

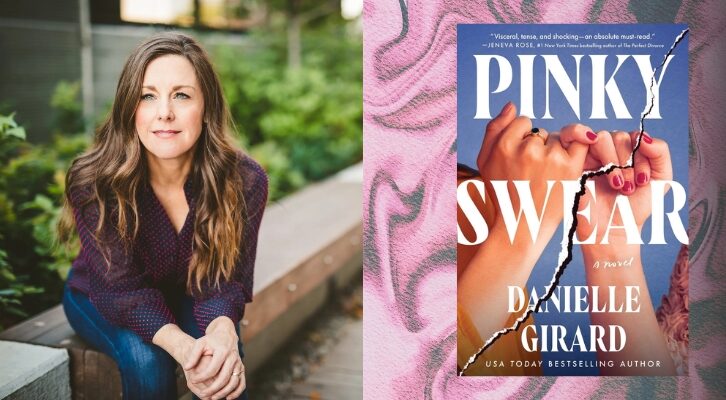

Jackie Higgins’ Sentient: How Animals Illuminate the Wonder of Our Human Senses is available now via Atria Books.

Jackie Higgins

Jackie Higgins grew up by the sea in Cornwall and has always been fascinated by the natural world. She is a television documentary director and writer. She read zoology at Oxford University, as a student of Richard Dawkins. In her first job at Oxford Scientific Films, she made wildlife films for a decade, for BBC stands such as The Natural World and Wildlife on One, as well as for Channel 4, National Geographic and The Discovery Channel. She then moved in-house at the BBC for a further decade, where she worked in their Science Department: researching and writing, directing and producing films across the board, from Horizon to Tomorrow’s World. She is also the author of three books on photography, a personal passion: The World Atlas of Street Photography, Why It Does Not Have To Be In Focus: Modern Photography Explained and David Bailey: Look. In Sentient, she returns to her fascination with the natural world. She lives in London with her family.