Working Writers: Nalini Jones on How Having a Day Job in Music Helped Her Write a Novel

The Author of “The Unbroken Coast” Riffs on the Power of Holding a Job in Another Industry

For John Schreiber

Most writers need day jobs. But I fled to mine when I believed I could never be a writer at all.

This was something of an embarrassment after a childhood devoted to reading. In fourth grade, I was discovered in the coatroom with a book propped on my knees long after recess; I never heard the class bells.

A year or two later I stayed home from school grieving for a boy in a novel about World War I; my mother mistook my weeping for illness. In high school, I swallowed the English courseload whole and took a job at the town newspaper, thumping the keys on a manual typewriter, certain my life had begun.

During all these stages, diagramming sentences on the chalkboard, filling blue books with rambling essays, holing up in my dorm for a weekend of takeout and Anna Karenina, I felt a kind of ownership over the experience of reading and writing. This is who I am, I thought.

It’s so easy now to see where I went wrong, conflating identity with pursuit. But in those years, my failure to write anything that lifted off the page felt unfathomable.

Most writers need day jobs. But I fled to mine when I believed I could never be a writer at all.

I don’t see a gift for fiction, a mentor told me after reading pages and pages of apt descriptions. I understood his candor as a gesture of kindness, an attempt to drag me out of an exhausting current. I was working so hard, getting nowhere. It was also a sign of respect, a reflection of the seriousness with which he was determined to consider my work. We shared the view that writing mattered. We agreed that my fledgling stories did not.

So I left the Pioneer Valley where I’d lingered after college and washed up in my father’s office, a bit of nepo-flotsam.

My father was a producer for George Wein, the creator of iconic music festivals in Newport, New Orleans, New York, and France. My sister, brother, and I had grown up working at their events. I was in the merch tent at age ten, the press office at eleven, the box office at thirteen. By high school I’d landed backstage, where I have stayed, one way or another, ever since.

Music production—from talent booking to logistics—is an unconventional day job. But I was never able to give it up entirely, even when I began to write again. It’s work that offers collaboration when writing is isolating, accomplishment when drafts are rough or slow or failing. It opens me to worlds and people about whom I am endlessly curious.

It illustrates the commitment a creative life requires; musicians stumble off the bus for an early soundcheck, rehearse in a corner of a dressing room trailer, stand on a dark loading dock, wait for a van long after the crowd has gone. It reminds me that we don’t need optimal conditions to do our work. It makes clear that art can be about fellowship and dialogue.

It has provided health insurance, I tell my writing students. It gave me a vivid connection to my father, and eventually the sense that I belonged in my own right. Once, when I was commiserating with a blues singer after a string of losses, she said, “The good news is that we’re still here, doing what we do.”

Sometimes I find myself wishing I could go back to the girl who read so many books that she imagined books were the point. Look up, I would tell her. Everything you need to know is here. From the stage wings, what has always struck me most is not the brilliance but the work, the striving.

The trumpet player drifts back during a drum solo, then piano, then bass. He is intent, rapt, listening with his whole body. Swing, I hear him whisper fiercely, swing, before he lifts the trumpet to his lips. He does not know what they will make before they make it. He plays to discover what the song will become.

Art comes from exploration. I have known this for as long as I was old enough to stand beside my father and hold a stack of stage towels as the band comes off after an inspired set, loose and laughing with each other, sometimes smiling down at me.

Yet for years, I tried to fashion sentences around ideas that seemed promising yet were ready-made. I was not brave enough to write into the murk of what I did not understand.

Once I began working full-time in music, I was free to think of writing in a new way.

Once I began working full-time in music, I was free to think of writing in a new way. I’d accepted that I might never be a writer and noticed that I kept on writing. There was no end-game, no lofty goals, no prospect of readers. Nothing beyond the impulse to try to imagine other lives, one word at a time.

It was only when I put aside the notion of books—books that seemed finished, composed, inevitable—that I could begin to explore the questions that have come to animate my fiction: questions about home and leaving home; about the unbearable and how we bear it.

The questions themselves are simple. I have heard them again and again in blues guitar riffs, in Sarah Vaughan’s voice, in the high lonesome sound of a bluegrass band. But “It is always a matter, my darling, / Of life or death, as I had forgotten,” as Richard Wilbur wrote to his daughter—and as a trombone player reminded me this spring when he asked for two extra stage passes.

He wanted to place them on the graves of his girlfriend and his mother, he told me, both lost to cancer, both at the heart of his endeavor. There is no end to what his quiet request has taught me about what art allows us to pursue: the chance to connect with the living, the hope of connection to the dead.

We listen to live music to experience the singular kinetic joy of hearing artists make those questions new and urgent again. And I go to the page for the plunge into stories those questions might offer. I often don’t know what will happen next, as a reader or a writer. Swing, I tell myself, swing. And begin.

______________________________

The Unbroken Coast by Nalini Jones is available via Knopf.

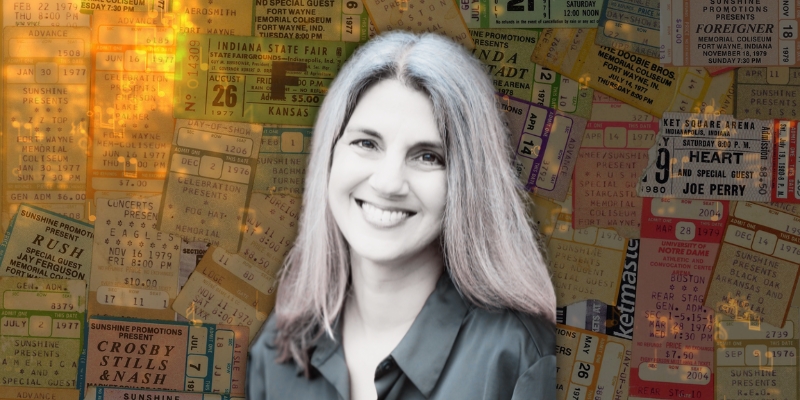

Nalini Jones

Nalini Jones is the author of a story collection, What You Call Winter. Her writing has appeared in One Story, Ploughshares, Guernica, Elle India, Scroll, and numerous other publications in the U.S. and India. She has been awarded a National Endowment of the Arts Literature Fellowship, among other honors, and her short story “Tiger” was selected for O. Henry and Pushcart prizes. She lives in Connecticut with her husband, daughters, and dogs, and teaches at Fairfield University.