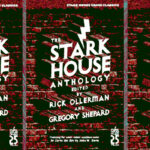

Work, Writing and Life in the New American West

Christian Kiefer and Josh Weil, in Conversation

I met Christian Kiefer a few years back, up at the Squaw Valley Community of Writers, and within an hour of saying hello he was sharing with me the story of his new novel, The Animals. Back then, it was still an unfinished book, and he was asking advice. He wasn’t happy with how the plot was working and he wanted to know what I thought about how to fix it. Most writers I know wouldn’t want to discuss their unfinished books, let alone point to the problems, and trust another writer they’d only just met to offer opinions about how to fix them. But that’s Christian, as I would grow to know him: a fearless writer, open and generous.

And, even if he (wisely) didn’t end up taking my advice (maybe because he didn’t), he wound up writing one of the best novels I’ve read this year. The Animals, Christian’s second novel is the story of two boys, neighbors in a small town trailer park on the east side of the Sierra Nevadas, brought together by the roughness of their lives and the way that, as they become adults, they try to help each other rise out of it—only to wind up dragging each other down.

Maybe it’s because I read The Animals while sitting on a sun-white rock beside the kind of cascading, clear river that you only get in the mountains of the American west, maybe because we both live in the foothills of those mountains, but when I got the chance to talk with Christian about his novel the first thing I wanted to ask him was about how the West—the idea of it—affected his approach to this book.

Josh Weil: One of the things that’s most striking about The Animals is the way it combines a level of artistry and literary daring with classic dramatic storytelling. The kind in the best noir novels, of course, but also, it seems to me, in westerns. Did you draw upon either genre? Were there any westerns or noirs—books or films—that had a direct influence on how you conceived of this novel?

Christian Kiefer: Way back when I first had the nugget of the idea that would become this book, I conceptualized it as a contemporary Western, which is to say a book about the Western hero’s “code” coming directly into conflict with the murky realities of the modern world. A lot of it has shifted out of that kind of thinking but obviously there’s still some of that material present, and of course the landscapes themselves are about as Western as it comes. I can’t think of any specific influences but I can tell you I’ve learned a great deal from Larry McMurtry, Cormac McCarthy, and Jim Harrison, all of which traverse this kind of territory.

As for noir, I’m embarrassed to say I’ve read very little of it as a genre but I do love the kind of gritty realism that generated from those writers (and from those films). I’m thinking about the fiction of Jodi Angel, Donald Ray Pollock, and Daniel Woodrell. Richard Ford’s Rock Springs would fit into that category too, in a lot of ways, but so would James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice. These are heavy books in which much—sometimes too much—is as stake.

JW: True, and that can certainly be said of The Animals. By the end, the entire life our protagonist has built is at stake (not to mention the safety of those he loves). I want to pick up on that idea of the Western hero’s “code,” though, the way it comes into conflict with the murky realities of the modern world. That’s at the heart of a lot of McCarthy’s work. I’m thinking of All the Pretty Horses, The Crossing, even No Country for Old Men. But, whereas so much of his work feels as if it’s set in a place and time that’s all its own, the modern world of The Animals feels very particular to this time. Especially the chapters in Reno when the friends are boys (so back a few years, but still contemporary); it feels like I could get in my car and drive across Donner Pass right now and find those neighborhoods, the flophouse hotel, those kids. Do you think there’s something about modern life now—I mean the time that we, you and I, are a part of, from when we were kids to what we face now as adults, that is especially in conflict with the classic Western hero’s code?

CK: I think the classic Western hero’s code was in conflict with its time even in the historical period in which it was supposedly most at home—the 1850s and 60s. Wyatt Earp went to Hollywood to get people interested in the OK Corral and it was him and others who really made that code into a thing. And yet it resonates to us because there’s some sense of clarity in its shape. Even suburban moms and dads are fierce when it comes to protecting their families—it’s not a cowboy ethic so much as it is, for me anyway, a family ethic. I know you’re a new dad yourself, Josh, so I know you know this—probably for the first time in your life you would actually kill another man to protect your child. God forbid it would ever come to that, but this was (and is), for me, something of a revelation.

Of course the kids (and later grown-ups) in The Animals, don’t have children, per se, but they do cling to some specific kinds of morality that guide their decision-making processes. And yes, McCarthy’s work feels like it takes place in some King James Bible version of the American west. It’s one of the things I love about it, actually. With The Animals I was obsessed with getting everything exactly right. I mean, the burl tables in one of the bars. The way the lighting was in this bar in 1984. That kind of thing. I wanted the reader to feel the sticky spilled beer on those table tops.

And that kind of realism, assuming I’ve achieved it, is certainly at odds with the clarity of the Western hero’s mythic moral code. When Shane decides—with much Western hero reticence—to pick up his guns again, the choice is clear and bright. Seldom are our moral decisions so clear and bright in the real world. Everything gets pretty muddy pretty fast. Throw addiction into the mix and all bets are off.

JW: I suppose realism flies in the face of any mythic moral code. Because it requires complexity, muddiness. Which brings me back to Jim Harrison, who you mentioned. I can see why: his characters are often wrestling with their own terrifically complex, muddy natures, with aspects of themselves that tilt them towards actions or desires that other parts of themselves know they ought to steer clear of. In your book both Nat and Rick are deeply flawed characters, characters who I wanted to hug in one beat and wanted to slug in the next (admittedly, I wanted to slug Rick more often). Was that complexity something that drew you to this story from the beginning?

CK: It sure was. I can’t think of a way to write about characters that makes them anything less than flawed. I think a great deal about how to be the best person—the best human being—I can, whatever that means. The decisions I make hinge upon my having a moment to puzzle at this. But often the decision—the good person decision—still isn’t as clear as I’d like it to be, because there are so many competing drives and motivations, some of which are not even my own.

What I’m getting at here is that people are flawed—all of us—but it’s not always because of things we’ve done. Often it’s just a facet of what Christians might call the post-lapsarian world. As an atheist, I just say that the human world is fucked up and we have to live in it.

Speaking of which, I think it’s time that I lobbed one back in your direction. In relation to flawed characters—or characters in general—might we talk some about Dima and Yarik, the dual protagonists of your novel, The Great Glass Sea? I was fascinated by these characters, but also troubled by them. These two brothers live in a time that feels like it borders on the mythic and they choose wildly different paths. Yarik chooses the machine; Dima chooses to rage against it.

In some ways, it felt like you wanted us to love Dima more than Yarik—and it’s certainly easy to do that since Dima’s the romantic one—and yet as a parent, it’s hard for me not to feel like Yarik is doing best by his people and that Dima is being a selfish child. I wondered if you’d struggled at all with this kind of reading? (I guess the real question is: Do you read this aspect of your own work differently now that you’re a dad?)

JW: You’re right, I did want readers to love Dima more than Yarik. Or, maybe more accurately, I simply felt closer to Dima; I understood him more fully. In some ways, he’s just more like me (which, admittedly, is scary). At least that was true in early drafts. But part of what turned The Great Glass Sea into what it is—both simply the length of the sucker, and, I hope, the complexity of it—was that the story kept telling me I needed to grow closer to Yarik, to see things from his side. Originally, it was all from Dima’s perspective. Now it shifts back and forth between the brothers. And, yeah, a lot of people find Dima frustrating, unrealistic, childish, selfish, and see Yarik in just the way that you described. I like that reading; it tells me I did my job. I didn’t want the book to be about one brother’s sadness; I wanted it to be about the tragedy that breaks them both.

And as to your “real” question? I hadn’t thought about that till now. But, perhaps surprisingly, the answer is no, it hasn’t changed the way I read that aspect of The Great Glass Sea. Surprising because having a baby has touched, in most every way, most every part of my life. But I already had sympathy for Yarik; I already knew he was the responsible one, the one looking out for his family, and that he was right to do so. That’s exactly the complexity of character we were talking about: I could see that, and know that, and still see the ways that Yarik was failing his brother, doing wrong by Dima for every right he did by his family. And I still feel that way. Maybe that’s because I can see all the wondrous ways in which my son has already changed my life, but I can also see the ways in which his presence has limited it, banished parts of it that I once loved. I mean, would Dima be a bad dad? Sure. In many ways. But he’s not a father. He’s a brother. And he’s a good brother.

But enough about those brothers. Back to your almost-brothers. And the question that’s kicking around my mind now: how did raising your sons (all six of them) affect the way you wrote these two boys? And their journey into adulthood, largely shaped by each other in the absence of the helpful hand of fathers? And the way that one of them, later on in his remade life, is affected by his step-father-like relationship with his girlfriend’s little boy?

CK: It occurs to me now that in some ways The Animals and The Great Glass Sea are both books about young men raising themselves, using each other as “parents” because they lack any kind of real, active parents. Yarik and Dima more or less make their own way in the world (the new world of The Great Glass Sea) and my two major characters—Nat and Rick—grow up fatherless with ineffective mothers. A good mother could just as easily have whipped them into shape but I’ve left them adrift, on their own, and so they rely on each other to learn what it is to be adults. Obviously, not the best situation. Perhaps that’s me wondering what my legacy is through my writing; I’m actually not sure.

I guess that as a parent I spend a lot of time wondering what the end result will be. My oldest is 21 this year and he’s turned into a wonderful, responsible, loving adult. But really I think I just got lucky with him. He grew up with divorced parents and stepparents and all the rest of it and yet somehow managed to weather it all.

On the surface, Nat (and later Bill) is a lot more like me in his thinking and his ways, or rather he’s a lot more like I might be given the same situation.

You said, above, something about feeling automatically closer to Dima. I wondered if you could elaborate on that a bit. After all, by your own words, Dima is “frustrating, unrealistic, childish, [and] selfish.” I wondered if Dima is, in some ways, a metaphor for the writer’s life in the sense that—at least from the outside—it looks like we spend a lot of time just fucking around. I did something a little similar with Keith Corcoran in my first novel, The Infinite Tides in that the character spends a lot of time in his own head—aka “the writer’s life.”

JW: We are selfish; we have to be. I think any artist has to be. The world doesn’t want us to write. It does everything it can to keep us from it. And the only way that I ever found to write with the focus that I need is to shunt the rest of the world aside—at least for a while. Now that the rest of the world includes my immediate family—wife, step-daughter, new son—that’s a lot harder to do. And when I do it, I wind up feeling like a pretty selfish bastard. So some of my connection to Dima might come from that. But I think it’s more the way he wants to live his life—stripped down, simplified, focused only on the things he loves most—that I connect with. For him, that focus is on his brother. I’m drawn to Dima because of his intense focus despite what’s practical, in the face of what the world expects of him. That’s the frustrating, unrealistic, childish aspect that I referred to: he clings to what he wants in life despite it being increasingly clear that life doesn’t want him to have it. And I often feel like that’s what I’m doing as a writer. So I respect his impracticality; I love him for his refusal to let his dreams be shaped by what the world tells him is possible.

You have a similar tendency, I think, in your own way, with your own work. I mean, you just up and created a record—actual pressed vinyl—to go along with your novel. Who does that? .

But you’re a serious musician, have put out some beautiful records, traveled with a band (in fact, you did so as part of the tour for your first book, right?) and for The Animals you created a haunting soundtrack, a kind of aural enhancement to the experience of reading the story. Can you talk about what your intentions and hopes are for the soundtrack? And, more generally, how your music affects your writing (and perhaps vice-versa)?

CK: I’ve spent a lot of time in the headspace of music, for sure, and it’s a different headspace than that of writing—at least for me. Maybe folks like Nick Cave and John Darnielle can navigate across those spaces with more grace than I can, but when I’m writing songs I’m writing songs; when I’m writing prose, I’m writing prose. Poetry sometimes flits between those disciplines but when I’m deep into a novel (or deep into writing an album) there’s nothing left for any other creative activity.

My friend William T. Vollmann somehow writes two or three books at once, makes prints, takes photos, and goes on adventures all at the same time. I don’t know how he does it, but it’s clear to me he has 15 extra brains crammed into his skull. For me, it’s definitely one thing at a time.

As for music, I almost made a soundtrack record for The Infinite Tides. I talked with Michael Krassner of Boxhead Ensemble about doing something with him for that book but it just never quite came together. The soundtrack for The Animals was made possible largely by the Internet. The glorious digital cloud allowed me to collaborate with musicians in Spokane and Tokyo and Brooklyn and all over the place, in addition to bringing musicians into my home studio. It all came weirdly organically, as if we all sat in a room and improvised music to a film. I made a 100-plus page visual “score” for the musicians to respond to—really just a collection of images and texts. It made it possible to contact my friend Jefferson Pitcher on the east coast and ask him to respond to, say, pages 56-58. A few days later I might find some new material from Jeff in my dropbox folder. It’s like magic.

JW : Ok, that’s all magical and interesting and everything, but what I’ve really been wanting to ask is how you do all this? I get the sense I feel about you the way you feel about Vollman. It’s hard enough for me to carve out the time to write but you write prolifically, make music, teach , maintain a marriage, and raise six (I’m just going to say this again: six) sons. How do you do it? Honestly. Writer to writer, I’m looking for advice.

CK: Ha! That’s the question I get asked all the time, but really, you should ask my wife that. She’s the one that makes it possible. She handles all the in-the-house/real-life stuff. I handle everything (almost everything) outside the house. So she cleans and cooks and takes care of the kids and I do the shopping and oil changes and that stuff. But really, it’s more than that (way more!). She understands that I need almost infinite time to do this creative work and she gives it to me by way of never, ever complaining about the time I take. She gets it.

JW: Good soul.

CK: She’s in the house right now, probably cleaning the kitchen after feeding the boys, and I’m out in the studio doing this. In payment I give her 100 percent of my income from everything I ever do. Clearly I’m the one getting the better end of that deal!

Really your question has more to do with being blue collar. I was raised in a blue collar household—something that I’m quite grateful for, actually. My dad was a mechanic and my mom was a waitress so it was all like a John Cougar Mellencamp song. But really that kind of life is pretty stressful for a parent but less so for the kids. There’s a kind of work ethic that I got from my folks. Anyone who has ever successfully completed a novel has that ethic; you have to if you’re going put your butt in the chair often enough to complete a manuscript.

JW: I once heard Colum McCann say something to this effect: that he can look at two students in a writing workshop, one of whom is the most talented, the other the hardest worker, and tell you right away which one is going to not only succeed in getting her work out there, but in getting her work to a point where it’s worth being out there. The hard worker, every time. And I remember the writer Chris Offutt saying to me that novelists are the salt miners of the arts, the ones who have to pound away at it day after day, year after year, put their asses in the chair and stay there for twelve hours straight trying to get a few sentences right. So I bristle when non-writers look all mooney-eyed at what we do and think, Now that’s the life. But, of course, it is the life. Because we’re doing what we love. And, after all, we’re talking about chairs and asses, here. Not pick-axes and pits of salt. Or even the everyday hardships and stresses of blue collar life.

Something you said about that struck me: how those stresses are felt more by adults than by kids. I see that in The Animals. The earlier scenes, when the friends first meet as children, are set in a world of pretty desperate poverty—and yet you manage to show that all around them, and make the reader feel the weight of it, without breaking the spell that is childhood, and I think you do it, in part, through the very recognition you pointed to: that the pressures their parents felt affect them, but don’t keep them from being kids. Of course, later in the book, those working class pressures are placed squarely on their own shoulders—and lead to disastrous results. In many ways, they’re at the heart of what drives the plot.

CK: Class is definitely an issue with Nat/Bill and Rick in the new book. These guys—especially as they appear in the 1984 timeline—are barely middle class. They’re living paycheck to paycheck, hardly making it at all. Part of it, for me, is thinking about being young and making bad decisions and having absolutely no safety net. Lots of my students at American River College come from that kind of economic situation. I’ve been there and who knows maybe I’ll be there again some day.

Having no money is like living in constant pain. You bounce a check so you have the bounced check fees. So then your bank account is under. And then you get paid and half your paycheck goes to those fees. And then you bounce again because you don’t have enough money, and the cycle just snowballs. It’s awful. Nat says something like, “There’s no getting ahead in this world.” That’s true for so many of us and it’s certainly true for Nat and Rick and all their friends. Especially so for Nat, as he has a gambling problem. But that’s just part of their economic class—once you’re already broke, it’s easy to make desperate decisions.

JW: If I remember correctly, in an earlier draft that gambling problem was Rick’s, not Nat’s. By shifting it to Nat you not only created a more complex character, opening up room for us to see things from Rick’s side, but you cranked up the narrative pressure by adding another level of desperation to the decisions that Nat makes. It’s one of the great strengths of the book: the way the plot emerges out of a complex understanding of the characters’ core natures, a result of their most human needs. And yet, for all the human understanding in the book, the section that stuck with me most was from the perspective of a bear. A grizzly bear, to be exact, a gutsy move. Especially as so much is riding on that section: it’s key—emotionally and narratively—to thrusting the story towards the novel’s climax. In the end, The Animals is about the choice between facing one’s fears or running from them. Would you talk a little about the role of bravery and fear both in the book and in your own beliefs about the writing of fiction?

CK: You’re right about the backstory having flipped. In some of the early drafts, Rick was a gambling addict and Nat was trying to help him. I knew there was a huge narrative problem in the book but I couldn’t quite figure out how to fix it, until I realized that I needed to swap their stories. It was a big rewrite—nearly half the book—but in the end it was necessary to make the engine of the book rev up the way it needed to.

Pushing ourselves to be better writers—that’s what it’s all about in the end. It’s a weirdly scary thing spending hours and days and months and years working on something when you really don’t know, at a core level, if it’s going to come together or be any good. I mean, I’m sure for us we feel like it’s probably good when we’re working on it, but until you have a final draft and you’ve worked out all the millions of tiny problems that crop up during the writing of any longform fiction, part of you is terrified. It’s like the end of that lovely James Wright poem, “I have wasted my life.” What if it doesn’t come together and my agent hates it and my editor hates it and I’ve spent some number of years doing something that dies on the vine? That’s the risk but I’ve got to be somehow ok with it, to accept it as the worst possible scenario. Spending two or three or ten years building a world and living with some characters is still a pretty good life, even if, in the end, it doesn’t amount to much. It’s better than being killed by a hippo.