Willie Perdomo on Poetry as a Decolonial Practice

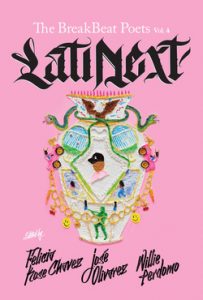

Introducing LatiNEXT, the BreakBeat Poetry Series

In March 2004, I was invited to Santiago, Chile to celebrate Pablo Neruda’s centennial. If you’ve been to Chile, you know that it’s a poet’s country. Copies of novels by Isabel Allende and poetry by Nicanor Parra are sold in subway vending machines like so many cans of sugary drinks or bags of potato chips. Taxi drivers and hotel clerks are well-versed in Neruda. If you walk through any market, you can hear the chant, “Libros! Libros, baratos.” In Chile, it’s not uncommon to look up and find that poems are being dropped from helicopters like bombs.

Read “December,” a poem by Jaquira Diaz from The Breakbeat Anthology Vol. 4: LatiNEXT

Along with workshops and visits to schools, there were the mandatory readings and performances. On a crisp Friday night, I was the featured poet in an event at Plaza Camilo Mori, which is located in the center of Barrio Bellavista. The stage was a portable lift on which I was raised to overlook the plaza. I read an ode to Chile, poetry, and Neruda that I had written the night before and that was generous in its use of Spanglish. At the end of my reading, the plaza erupted into an applause and affirmation that one might find at a political rally. My use of English and Spanish was a revelation to some of the poets in the crowd. The audience in Plaza Camilo Mori had never heard Spanish and English in a poem. They were witnessing a LatiNEXT moment. For some of them, it was something new. For me, I was like: This is what we do.

The BreakBeat Poetry Series offers a poetics that, like hip-hop, is in constant search of new forms, new utterances, new languages, freshness. Every day a new regulation, a new assault, is hoisted on the Black and Brown bodies of this country whether they are immigrants or native sons. If poetry is truly a decolonial practice, then this anthology lifts its lyrical machete, its formalistic authority, its innovative approach toward language, its queerness, its nonbinary they, its sense of lineage, family, tradition, pride, and, refreshingly, its Blackness.

You will find poems by Elizabeth Acevedo, Raquel Salas Rivera, Sara Borjas, John Murillo, Daniel Borzutsky, and Vincent Toro—poets who are in conversation, in celebration, in protest, in demonstration, in a collective breakbeat that is informed by ritual, but also a resistance to the normalized ways of looking at stanzas, patria, sex, gender, patriarchy, and nationalism. This anthology is standing right next to the street activists and professors, slam poets and National Book Award winners, MCs, and youth poets. And it does so humbly, aggressively, fearlessly, jokingly, multilingually, and, at the right moments, with bravado.

If poetry is truly a decolonial practice, then this anthology lifts its lyrical machete.

Pablo Neruda, like Amiri Baraka, maintained that if you can’t read your poem to a fruit vendor, a construction worker, a crossing guard, then your poem is worthless. The tradition of Latinx poetics ranges from the super elitist traditionalist who still holds on to what Audre Lorde called the “master’s tools,” to MCs like Big Pun. We rock like that, and we make room at the table for that range. In this book you’ll find poets who are at the start of their poet lives, poets who are at the peak of their careers and still trying to challenge themselves, and poets who might not ever write another poem.

The Latinx demographic in the United States has changed. Facts. We are in the majority. Facts. I think the Trumpistas and rabid protectors of the white ethnostate know that we are in a somos más moment and that poets might play a key role in that moment. And we should be aware that this is just a sliver of who is out there poeting. We would need another anthology just to accommodate the ever-growing nation of Latinx and Hispanophone Caribbean poets across the nation and abroad.

This past summer, “El Verano de Puerto Rico” combusted when a group of students, rap stars, pop stars, politicians, motorcyclists, scuba divers, poets, grandmothers, activists, and justice warriors, peacefully took to the cobblestoned, colonized streets of San Juan, shouting “Somos más y no tenemos miedo,” and demanded the resignation of Ricky Rosselló, a legacy politician who, at the time, was the presiding governor of Puerto Rico. The demand was simple: Ricky had to go. He was exposed as a misogynist who also made fun of residents, mostly poor, who suffered terrible losses in the destructive torrent of Hurricane Maria. At the vanguard of the movement were women with names like “Tita Molotov” who chanted and banged on pots and pans until the governor and his staff listened. Ricky has since resigned, and now the galvanized movement has other targets in its sight: La Junta, disaster capitalists, hedge-fund vultures, and the Jones Act which, to this day, has had an enfeebling effect on Puerto Rico.

Poets, voluntarily or not, consciously or not, are engaged in a moment of resistance to definitions, monolithic stereotypes, and outmoded ways of looking at the Latinx experience. No one has the upper hand or singular authority on being Latinx, queer, trans, biracial, Black, fluent, or claims to the best pasteles, mofongo, or horchata. The mezcla, or the remezcla, is where we are going to find our strength, our vision, our power, and it’s in these pages where you’ll find the blueprint, which is simultaneously frightening, magical, and real. Welcome to this somos más moment.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Breakbeat Poets Vol. 4: Latinext. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Haymarket Books.

Willie Perdomo

Willie Perdomo is the author of three previous poetry collections: Where a Nickel Costs a Dime, a finalist for the Poetry Society of America's Norma Farber First Book Award; Smoking Lovely, the winner of the 2004 PEN Open Book Award; and The Essential Hits of Shorty Bon Bon, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His work has been published in The New York Times Magazine, Poetry, BOMB and The Common. Perdomo teaches at the Phillips Exeter Academy.