William Dameron On the Tricky Art of Turning Truth Into Fiction

"As authors, we become the ones we love, and we write them into existence."

I never intended to write about my family again, but when Covid-19 hit, none of us knew we’d been sealed into shrink-wrapped containers with each other for the next two years. My pandemic package included a husband, a couple of nearly adult kids, aging in-laws, a visiting sister-in-law, and a nephew. The setting was southern coastal Maine. You know the story. Each day blended into the next. We became unlikely caregivers. We baked bread and made unique and intriguing cocktails. We hoarded toilet paper, and we lost time.

During that first year, I accomplished what many of my writer friends did—nothing. That is to say, I did anything other than write or read. Of course, there were the trays of seedlings that required my doting attention, the endless walks to nowhere, and the peel-and-stick wallpaper to be hung. 2020 was the year after my debut memoir, and coming off that high was a spectacularly emotional low. We’re talking about the type of crash-and-burn scene my husband relishes in his favorite action genre, “films.” As a nonfiction writer, reality became too exhausting, and I could not conjure a world beyond the four walls of my existence. When my agent, Christopher, called to check in on me, (read: what have you been doing?) I used my only defense—tears.

After those cleared up, he advised me to jot down what was happening in my life, the overheard bits of conversation, and daily activities. “Make a record of life happening.” Christopher knew something then that I did not: sometimes, just showing up is enough. Miraculously, the logjam broke, and after several months, I presented a proposal and one hundred sample pages to my publisher for a second memoir.

We should not write what we know but what we don’t know about what we know.

And this is where the story should end, except it doesn’t. Imagine my covid-weary editor’s response: A pandemic memoir? Yes, please!

I was assured my publisher loved working with me. The “but” was implied.

“They have something a little different in mind,” Christopher said.

“Something out of left field, huh?” I asked.

There was a pause, and then he said, “Another field, like three fields over. Maybe a different sport.” He took a breath, “They love the premise.”

But here was the plot twist. They wanted it as fiction.

Some authors turn their nonfiction books into fiction to avoid legal issues. I lost sleep over this when I published my first memoir. In it, I shared intimate details about my ex-wife, daughters, husband, and mother. With that book, perhaps I was more concerned about matters of the heart than legal matters, though I needn’t have been. As one of my southern writer friends put it, my 82-year-old mother “Went all mama bear” and jumped into the comments section of a New York Times essay to defend me against a disparaging remark. But this time, my publisher was less concerned about legal issues.

“So, how does the book end?” my editor asked.

“I think he’s waiting for someone to die,” Christopher replied.

“It might be the reader,” she suggested.

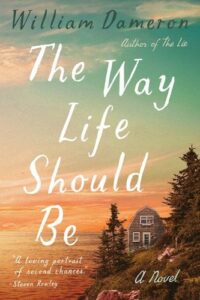

And so I took my publisher’s advice and created a new book, my first novel, The Way Life Should Be. While the setting is the same, the plot is new, but the characters bear the unmistakable imprint of their genesis. Like a sponge, have I not only soaked up the essence of my family but also the overheard bits of conversation, whispered musings, and squeezed those too out onto the page? Did I used my family members to get over writer’s block?

Grace Paley, the inimitable American short story writer, teacher, and political activist, said, “You write from what you know, but you write into what you don’t know.” In other words, we should not write what we know but what we don’t know about what we know.

Like Grace Paley, whose short stories revel in the quotidian details of her daily life in the Bronx and Greenwich Village, I have recreated my world of Maine on the page. But unlike Ms. Paley, whose mastery of wry dialogue and description of life’s repetitious activities are elevated into stunning prose, I cannot achieve that same quality with description alone. I must introduce a surprising (I hope) plot.

I have taken what I know, the people I love who are closest to me, and placed them in untenable situations. I have peered into their imagined bedrooms, bathrooms, and the depths of their souls and caught them in embarrassing and self-harming acts. To paraphrase Nabokov, I have put my family up in a tree and then thrown stones at them—started with what I know and wrote into what I did not know.

This permission to make up stuff saved me. The metaphorical mighty pen allowed me to pierce the plastic bubble and escape into a world where the pandemic did not exist. I could breathe freely again, even as my characters grappled with the most challenging moments of their lives, abuse, infidelity, self-medication, and confronting childhood traumas. In fact, my family had been facing some of the most grueling moments of their lives, the pandemic, ailing parents, and loss of hope. However, I gave their avatars a different set of challenges to overcome, and in that process, they became who my family was not, nor will they ever be, because they only exist on the page.

Or do they?

Like my first book, I did not give the manuscript to anyone in my family until the edits were complete. Unlike my first book, several family members anxiously put the manuscript down, before taking a breath and diving back in. They identified too intensely with the characters, and felt untethered by the foreign terrain. There were guardrails in my memoir, but in fiction, I allowed them to run off the rails.

“How will my friends know where reality ends and fiction begins?” one asked.

“It’s all fiction!” I replied.

And honestly, it is, but isn’t all creative writing fiction?

The metaphorical mighty pen allowed me to pierce the plastic bubble and escape into a world where the pandemic did not exist.

In his novel, The Story of a Marriage, Andrew Sean Greer’s protagonist muses, “We think we know the ones we love. Our husbands, our wives. We know them—we are them, some-times; when separated at a party we find ourselves voicing their opinions, their taste in food or books, telling an anecdote that never happened to us but happened to them.”

As authors, we become the ones we love, and we write them into existence. Every character on the page of my novel is me, but isn’t this also true of my memoir, appropriately, or perhaps ironically, titled The Lie? The difference is that in my novel, I have shifted from first person to third, and I tunnel into my character’s minds, which is really my mind imagining their thoughts. Perhaps this is one of the things my loved ones cannot bear, the existence of their supposed secret thoughts as conjured by me. Everyone loves a mind reading card trick, but take away the cards and all bets are off.

My family knew the plot of my first memoir because they lived it, and it was an accurate record of events, to the best of my knowledge, as they occurred. It is, perhaps, more difficult for my family to confront in my novel what my imagination could do to them—give the characters who bear a resemblance to my nephew a nipple piercing, and force a Sister-In-Law into an extramarital affair, than what I have done to them, which in my mind has, at times been far worse.

“Did I tell you that?” one of my family members asked after reading a passage about a character’s internal thoughts. The truth is, I’m not certain. I am like Thomas, one of the main characters in my novel who muses. Sometimes Thomas forgets which memories are his, and which belong to Matt: The majority of Annie and Matt’s happy childhoods played out on Norfolk Road. An entire childhood where the Brady’s home was ground zero. How could Thomas not want to claim Matt’s memories for his own?

Readers often ask novelists, “Which one are you?” as if the authors must insert themselves as a single character into the story. Here is the truth, at least for me; the correct answer is both all of them and none of them. We are many. I am no one.

Behind the scrim of fiction lies a world of infinite potential, one where the author can slip into the skin of those he loves and hates and imagine the best and worst of possibilities. In this place, if the writer has succeeded, emotional truth reigns, even in the realm of fiction. We walk that tightrope between emotional fact and fiction where if (spoiler alert) some of our characters—people we dearly loved—die, they can be brought back to life.

__________________________________

The Way Life Should Be by William Dameron is available from Little A, an imprint of Amazon Publishing.

William Dameron

William Dameron is an award-winning blogger, memoirist, essayist, and author of The Lie, a New York Times Editors’ Choice. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Times (UK), Telegraph, Boston Globe, Washington Post, Salon, HuffPost, Oprah Daily, Saranac Review, Literary Hub, Hippocampus Magazine, and in the book Fashionably Late: Gay, Bi & Trans Men Who Came Out Later in Life. He is an IT director for a global economic consulting firm, where he educates users on the perils of social engineering in cybersecurity. William and his husband split their time between the coast of southern Maine and Florida. For more information, visit the author at www.williamdameron.com.