How Casting Helen of Troy Becomes an Exercise in Female Power

“Helen’s spell has always depended, in part, on her own erotic agency, exercised in defiance of male authority.”

The movies’ obsession with beauty would seem to make the role of Helen of Troy, as one 1950s Hollywood-watcher put it, “the choice film assignment of all movie history.” The selection of an actor for this assignment must begin with a “beautiful” face and figure, but it cannot end there. Beauty and especially glamor are sometimes associated with impassivity or lack of movement, but if a woman looks her best in still photographs, her beauty is not “stageable.” In a motion picture, a static, expressionless face, however well proportioned, is alienating rather than alluring. (It is no accident that “wooden” is a standard descriptor for poor acting.) The performance of beauty, in so far as it depends on the close-up, requires particular subtlety. As one beauty advisor warns us, a blank expression “will ruin the best of good looks.” An actor’s voice is also important, especially considering voice’s time-honored role in the expression of seductive femininity.

The performer’s effectiveness thus depends not only on her features but on her ability to employ the resources of gesture, demeanor, and voice—in other words, to act. As Hedy Lamarr put it (and she should know), “You can’t just take some bosomy cutie and by giving her some sexy lines and tight costumes create a glamour girl. Sophia Loren would be a glamour girl even if she were in rags selling fish. She has the look, the movement, and the intellect.” A powerful performance can even trump supposedly “objective” appearances. Bette Davis, for example, is not conventionally beautiful. According to Molly Haskell, “She was universally considered unsexy” in Hollywood, “not to say unusable”; nevertheless, Haskell argues, she has a beauty and charm that are “willed into being”; she convinces us that she is beautiful and sexy “by the vividness of her own self-image.”

The next question is whether to cast an unknown or a star. Helen’s mythic identity would seem to situate her at the apex of the star system, which was occupied, in Hollywood’s golden age, by “that unique creature, the film goddess—one who provokes admiration, imitation and sometimes the most total and irrational devotion of a multitude of worshipers.” Such stars, often referred to as “love goddesses,” become public signifiers, allowing audiences to draw on the collective desire that is produced and reproduced through circulation of their images. This kind of iconic energy is concentrated in the sex symbols of collective fantasy—the Marilyn Monroes—whose burden of erotic signification far outstrips their identity as individuals.

Yet even the most brilliant star is at the same time a “real” person whose life extends beyond her screen presence, linking her many manifestations to provide a measure of coherence and continuity. There is a mutually reinforcing synergy between this “real” identity and a star’s onscreen performances. The effect is further enhanced by the nature of star acting. In so far as the essence of stardom is “to be recognized within and beyond any role,” stars are not expected to act in a way that conceals their identity. Rather, “the star is permitted to underact … and this underacting produces the effect that the star behaves rather than acts.” In the case of great beauties, this means they perform not by impersonating others, but by radiating personal charisma.

The studios bridged the gulf between love goddesses and their admirers by constructing elaborate star personalities, which typically rest on a foundation of “ordinariness.” This helped fans to feel a personal connection to their screen idols, a sense of intimacy fostered on screen by techniques like POV shots and close-ups, and outside the cinema by such memorabilia as letters and signed photos—ordinary objects endowed with a numinous presence. Star casting thus connects us with the “real” person of the star, even while presenting her as a mythic figure, unattainable by those who gaze on her beauty from afar. She is a “magical reconciliation of opposites,” “at once ordinary and extraordinary, available for desire and unattainable,” ideal yet real, generic yet individual, public, yet private; “powerless, yet powerful; different from ‘ordinary’ people yet … ‘just like us.’”

Star discourse is thus—like mythology—a means for managing paradox. We can see this at work in the caption describing Joan Crawford in Waterbury’s Photoplay article. She is “Venus rising from the movies. Just a modern girl, but Joan Crawford…” Crawford—who was indeed, in this period, a rising star—is simultaneously a specific named person, a Greek goddess, and a modern American “girl.” The star’s paradoxical identity also conditions our response to her performances. A contemporary reviewer of Flesh and the Devil declared Greta Garbo, as the vamp character, to be “believable” as a real woman, and as an object of male desire, yet at the same time “both real and unreal until she finally becomes a symbol of sexual appeal rather than any particular bad woman.”

The recognition essential to stardom might seem to preclude a sense of immersion in the past. There is, however, a sense in which star casting can actually enhance the representation of historical figures. Star power can seduce us into overlooking the “credibility gap” between actor and role, and star status can assist in representing “not real historical figures but rather the real significance of historical figures.” As George Custen explains, when Queen Elizabeth I is played by a star like Bette Davis, “the moviegoer is drawn to resonant aspects of the impersonator as well as the life impersonated … One admires Queen Elizabeth I for her statecraft but also because she is Bette Davis.”

Like a love goddess, Helen is an icon of beauty and glamor, whose looks and love life are an endless source of public fascination, evaluation, and judgment.

If this is true of a role like Elizabeth, a historical figure whose appearance is familiar from portraiture, it is far more so of a mythological creature whose likeness exists only in the imagination. Like the gods and heroes of mythology, stars are anthropomorphic divinities, transcending mere mortals in beauty and prosperity (if not morality). They reach us mediated by verbal and visual representations, which perpetuate their renown, while remaining open to endless manipulation and reinterpretation; they serve, in complicated ways, as models or ideals; they shine—both literally and figuratively—with the radiance of heavenly bodies, which is an expression, in turn, of their personal beauty.

The homology is especially compelling in Helen’s case. It is no surprise to find a Greta Garbo fan addressing her idol, in a poem, as a goddess who is Helen reborn. Like a love goddess, Helen is an icon of beauty and glamor, whose looks and love life are an endless source of public fascination, evaluation, and judgment; she is simultaneously superhuman and “real,” endowing material objects with a numinous aura; she is identified with her reputation and captivates even by report, or through her intentionally constructed image (eidolon); she is not only eternally young and beautiful, but seductive, evasive, and available for fantasy and appropriation by fans and admirers, who may fall in love with her without ever having seen her in the flesh.

These parallels posit Helen, like a movie star, as an object of desire, emulation, envy, blame, or gossip. Yet Helen’s spell has always depended, in part, on her own erotic agency, exercised in defiance of male authority. The glamor of the love goddesses, similarly, “carries with it the right to romantic domination [so that] they are free to assert their own sexual desire independent of patriarchal control.”

As the “trump of trumps” for women in Hollywood, beauty could also be the avenue to a different kind of power. Like the Greeks who created Helen, the film industry shapes star images for its own purposes. Yet “the money, fame, and erotic desirability with which the industry has endowed them” can render them, at times, “more powerful than the men who created them.” Among other things, they may gain control of the very image that empowers them. Granted, only the greatest female stars exercised (or exercise) much real power in Hollywood. Yet films like the perennial A Star Is Born (1937, 1954, 1976, 2018) continue to dramatize their emasculating threat. A bona fide star who takes on the role of Helen may thus be in a position to appropriate the power that radiates from her iconic beauty and dominate her own film. This means that the story of casting Helen is itself a story about female power, and specifically the ability of women to parlay the passive power of the desirable object into the power of agency. For all these reasons, star casting seems like the perfect solution to the kinds of representational difficulty that she embodies.

Casting an unknown helps to reduce the “eternal feminine” to someone with whom any woman can identify and whom any man can aspire to possess.Despite this synergy, however, the role has often been filled by a minor player or a complete unknown. The lack of audience recognition is thought to render such performances more “human” and “believable,” and thus more “realistic,” than a star turn. Casting an unknown helps to reduce the “eternal feminine” to someone with whom any woman can identify and whom any man can aspire to possess. Such treatments tend to focus less on Helen’s exceptionalism than on her ordinariness (a form of “realism” often used to humanize mythic figures). To embody transcendent beauty successfully an actor must be not only individual, but iconic; and an unknown is liable to come across as less iconic because more ordinary. In such cases, Helen’s mythic supremacy is sacrificed on the altar of Hollywood “realism.”

Yet unknowns are not entirely excluded from the star system. Such casting is often accompanied by the publicity stunt of a beauty contest or “worldwide search.” The lucky winner’s performance is not enhanced by a preexisting star aura, but she does come with a (presumptively male) seal of approval, which raises certain audience expectations. This is a risky casting strategy, which fails unless it takes hold via the kind of breakout performance through which a star is “born.” No matter who is cast as Helen, however, or how she is shaped by the work of the actor, director, writer, or designers, success in the role depends ultimately on the fickle judgment of that modern Paris, the movie audience.

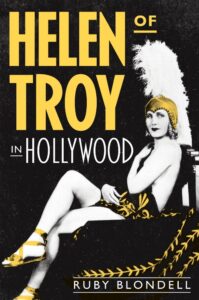

My book offers a series of case studies, each examining ways in which the figure of Helen is both shaped and judged in various contexts. For each work, I ask: How does it address the problem of representing extraordinary beauty as an inheritance from Greek antiquity? Who is cast as Helen and how do they look, dress, and act? How is our response to them mediated by such factors as genre, narrative, cinematography, and mise-en-scène? How does each Helen reflect and refract conceptions of beauty, and anxieties about its impact, within the specific historical and cultural context in which the film was made? How does each work use her to examine female sexuality and erotic agency? How does it craft its appeal to disparate viewers? How does it position itself in face of the alien yet familiar culture that it purports to represent, cuing dialogue between ancient and modern? How does it harness the cultural authority of ancient Greece, and specifically of “Greek” beauty, to flatter, lure, or challenge its intended audiences? And finally, how did audiences respond?

_________________________

Excerpted from Helen of Troy in Hollywood by Ruby Blondell. Copyright © 2023 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.