At the beginning of each little chapter you walk through a doorway. There is the detail of a coffee cup, a mirror, a pear. You must raise the hand to hold, the face to look, the mouth to drink. You supply the blood to the text, the fullness is the fullness of our own flesh. This is why the heart beats with Anna Karenina.

This might be the definition of a domestic novel, one that is entered through such doorways. But we have decided, for various reasons, that this one takes place on the world stage.

I tried to read it when I was young, perhaps even the Maude translation. It was my mother’s high school copy, the color of tallow or bone, with Anna in profile on the cover wearing a ring of pearls. And I saw something when I read the word ball, which must have had to do with Cinderella. It descended from the ceiling, and was round like a pumpkin, and it opened. And it lowered and lowered until everyone was inside it, dancing in that clockwise whirl of skirts that I felt around my ankles. The shape of the skirts echoed the shape of the word. White necks rose into conversations. What they were saying did not matter much; the real excitement was being at the ball. Entrances and exits, and snow, and Progress, and the horizontal shape of what was coming.

“Anna read and understood, but it was unpleasant to read, that is to say, to follow the reflection of other people’s lives. She was too eager to live herself. When she read how the heroine of the novel nursed a sick man, she wanted to move about the sick‑room with noiseless footsteps; when she read of a member of Parliament making a speech, she wished to make that speech; when she read how Lady Mary rode to hounds, teased the bride, and astonished everybody by her boldness—she wanted to do it herself. But there was nothing to be done, so she forced herself to read, while her little hand toyed with the smooth paper‑knife.”

The instrument of her destruction is not the train. It is her body, slice, slice, moving us from page to page. The satanic quality of Anna is her need to move, to and fro in the earth and up and down in it. Not to read but to be alive, her eyes so open in the dark she herself can see their brightness.

Vronsky considering the black trousers that contain Anna’s husband’s legs.

How far did I get the first time? I remember Levin gave me trouble, and his farm and his articles and his brother Nicholas’s musings on capital. But I remember those little brown rooms too; I must have tried to move through them. And understand! The surplus value . . . of labor? And the word ruble. A cube of cool raw potato in the mouth.

“Karenin was being confronted with life—with the possibility of his wife’s loving someone else, and this seemed stupid and incomprehensible to him, because it was life itself.”

Anna Karenina. This idea, in reference to Sviyazhsky, of the reception rooms of the mind. What if there were a person whose mind had no reception rooms, but who carried you immediately into the tabernacle?

*

When his love is answered Levin becomes like the crystal you set on a newspaper to magnify it, and what leaps toward him is the knowledge that other people love him. The process of asking and answering is what makes the whole language transparent.

My skin was running races. This meant that I was looking at art, reading literature, listening to music; or that I was in the ocean, with a wave breaking just at my waist. It meant that I was reading the scene in Anna Karenina where Karenin pulls Vronsky’s hands away from his face so that the shame can run out of him and rejoin the natural blushes of the world: sunrise, sunset, fruit, flowers. No shame, no shame, I said to myself, pink peaches.

What if Karenin had breastfed the baby? Karenin should have breastfed the baby.

But Karenin can only be a saint in a world with no other people.

His sainthood even requires the removal of the one he forgives.

Karenin believes that his coat has been stolen from him. He turns it inside out and finds it full of violets. These are forgiveness. He believes they are something for him to hold and keep holding, when forgiveness must mean to keep reaching, inside the sleeves and the pockets and the shape of the thing we are certain is gone. This is the turning of the cheek. This is the seventy times seven. Keep searching and you will keep finding flowers, and your job is to give them away.

Tolstoy—the selfishness of the holy feeling, how it is people that stop us from pouring out our generosity upon them. Inside us our feelings are perfect, as people were perfect in the garden. How good we could be on an empty earth! Hence: utopianism, vows of chastity, the handing over of the diary containing all our sins, because the scrubbing of the soul is paramount. My father did this to my mother, apparently, after his conversion. And what am I, she cried, chopped liver?

But the soul is a floor. It is there to bear us up and keep us standing, not merely to be clean.

Strange how in Anna Karenina it is the women who draw these feelings out of the men, but the men who are saints.

Holiness is not about feelings. It is about considering how the other body is lying under the blanket. And perhaps it does require that period of rehearsal. Kitty’s playacting in Soden becomes real. She actually has learned how to take care of the dying.

That religion that Karenin takes up, under the oversight of Countess Ivanovna, is his attempt to hold on to that feeling, to grasp something tightly in his human hand. But that is where you hold money. It is not where the real thing is felt. The real thing is that the son believes in his mother. That he does not believe in death, especially not her death.

And what do they want Seryozha to learn? “That the word suddenly was an attribute of the manner of action.”

Anna restlessly moving her paper‑knife in the book she cannot read on the train, Seryozha notching the edge of the table with his—both of them refusing to learn the prosaic lesson, the water that is expected to turn mill wheels working somewhere else in them.

Sometimes the detail through which we enter is not material but spiritual, and the room is not the room at all, but a being. I am thinking of us briefly landing on the bare foot of the peasant, and the imprint in the dust “with its five toes.” I am thinking of those brief paragraphs on the marsh when we go into the consciousness of a dog, Laska, with her mind full of they they they and where, and the master coming toward her with his “familiar face but ever terrible eyes,” because until she tightens her circle down to that pupillary point she does not know what he wants, what he would have her do.

Always it is social custom and even language that leads us astray. Anna alone is direct as a ray, she is pure emotion, rising into the fullness of her shoulders, her neck, the curls of her hair. Her hands are her action, reduced to restless movement because they have no span. And the child of her love, the “dark‑browed, dark‑haired, rosy little girl, with her firm ruddy little body covered with gooseflesh” is described as a little animal too.

Tipsy Levin’s encounter with Anna’s soul, which first emerges from her portrait toward him and then steps forward in the figure of a real woman. To Levin especially it speaks, that directness of a ray.

Where is the detail that first allows us to enter the body of Anna Karenina? For we are not just inside the actual tempo of experience, which so struck Nabokov that he began scribbling out train timetables, but inside her body as it moves. It is her bust where he has centered her life, as a sculptor would; we never see her feet or legs as we do twinkling Kitty’s at the ice rink, in her skating costume so short and tight that Nabokov had to draw it. It is also where he centers the involuntary exercise of her strength; that ray that pours toward any man she meets, and that they experience as seduction, also pours toward us. The portrait of her steps out of its frame.

In the scene of Kitty’s childbed Tolstoy abdicates this sense of metronomic time and allows Levin to live several days at once: one trapped inside the horror of his bursting heart and body; one on the eternal plane of love with Kitty, staring into her flushed face and holding her hand; and one with God.

Take off my earrings, Kitty cries, they are in the way.

Levin, of his son: “It was the consciousness of another vulnerable region.”

In these situations of extremity people do become the thing called saints, because they give up their rational minds and allow their bodies to do what they know how to do.

Why didn’t the Beatles ever write a Tolstoy song—“Thank You, Mr. Tolstoy,” “Mr. Tolstoy, You’re Driving Me Mad,” etc. The first lyric could be, “Anna Karenina, you’re a fat one.”

*

It is so alive that you still feel that the course could be changed, when we are in that sleepy room with the charlatan Frenchman. But then there is that deadness that enters into the closing chapters, which might as easily be called inexorability. It is because her death has been foreordained, by the news item that jumped to Tolstoy’s eye. The composition is now a matter of transport; we ourselves are in the train that will take Anna under its wheels. The sign of the cross she makes before she jumps is not alive, it is only from life. It is the detail of the candle that allows us to enter her, and see the whole scene by the last of its light: Anna dropping to her hands and knees before us, when previously she has not made an ungraceful movement for seven hundred pages, and disappearing under the velocity that has joined her time to ours. And who is there to forgive her? The next chapter opens two months later; we have rapidly passed on.

There can be none of that surprise that was present in those earlier scenes of extremity: Anna ordering her husband to forgive her lover—to release her lover’s shame—on her first and incomplete deathbed.

Vronsky now, when looking at the smooth movement of the wheels over the rails, will always see her face.

Anna fastened her meaning on Vronsky; Levin fastens his meaning on the land. “In this way he lived, not knowing or seeing any possibility of knowing what he was or why he lived in the world, and he suffered so much from that ignorance that he was afraid he might commit suicide, while at the same time he was firmly cutting his own particular definite path through life.”

We have received your opposition to the railroads, Tolstoy. We will return to the land and keep bees.

We must live for something incomprehensible. Karenin is wrong, doing his little taxes for God; Anna is wrong, building her hospital. Lydia Ivanovna was so wrong she was evil. But Kitty is right, considering how a man’s body is lying under a blanket.

To be right is to do what our bodies know how to do anyway, and not ask why. “Take off my earrings”

Tolstoy must have felt that he was full of love, and that his love somehow curdled when it hit the air. He must have felt that words exchanged in conversation almost always go wrong. But words delivered in a tract, say, seven hundred pages—and no one can interrupt! No one in the world is your wife, and everyone is the girl as she was when she first encountered you.

“He was glad of this opportunity to be alone and recover from reality, which had so lowered his spiritual condition.”

The holiness that he felt really was a sort of concentration, which perceived as its enemy anyone who might break it. But this also is an attempt to hold on to the violets; you must give your concentration away so it can return to you. And no I cannot do that either, it is impossible!

Indulge me for a moment in believing that characters really breathe. The choosing of Vronsky is Anna’s human impulse, but it is Tolstoy who decides that she will die. It is Levin who chooses Kitty, and it is Tolstoy who chooses Jesus Christ. We are more like Laska than we are even like Seryozha, with our noses at every moment catching the wind, and our consciousness at every moment full of They They They.

__________________________________

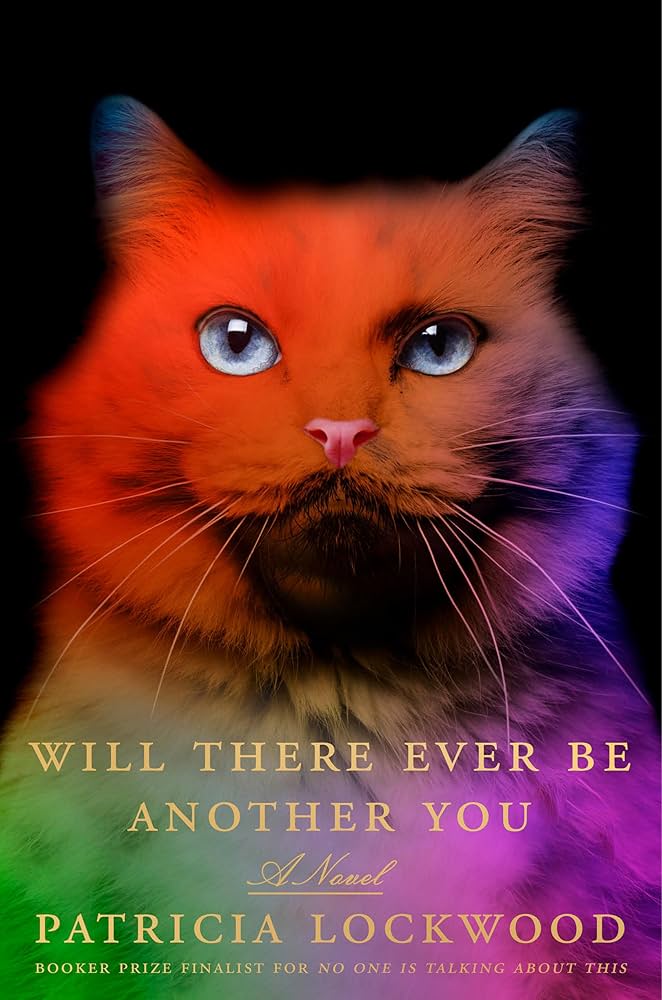

From Will There Ever Be Another You by Patricia Lockwood. Used with permission of the publisher, Riverhead Books. Copyright © 2025 by Patricia Lockwood.