Why You Shouldn't Cross Meryl Streep on a Film Set

When Dustin Hoffman Crossed a Line Making Kramer vs. Kramer

Perhaps you’re aware that Meryl and Dustin clashed on the set of Kramer vs. Kramer. If not, prepare for a cautionary tale in how not to treat your coworker.

Several years before, Meryl encountered Dustin while auditioning for a Broadway play he directed called All Over Town. She was in school at Yale; he made a terrible first impression. “I’m Dustin Hoffman,” he said, burping and groping her breast. Little did she know that someday this brute would be her movie husband. (Dustin is said to have apologized later for that incident.)

Like Billie Jean King preparing to outplay Bobby Riggs, Meryl had done her warm-ups. She hung around Upper East Side playgrounds to watch young, nonworking moms dote upon their kids and began to empathize with her character’s internal struggle: “Joanna’s daddy took care of her. Her college took care of her. Then Ted took care of her. Suddenly she just felt incapable of caring for herself.” Meryl, of course, had experienced none of that in her scrappy life. “I wanted to play a woman who had this feeling of incapability, because I’ve always felt that I can do anything.”

On the second day of shooting, Dustin crossed a line. They were filming Joanna’s dramatic exit at the very top of the film, when a distressed Joanna, trying to keep it together amid tears, bluntly informs Ted that she doesn’t love him and she’s leaving—without their son, Billy. According to Meryl, “We were supposed to emerge out into a hall, so we started out in the room, behind the door, and they said ‘Action,’ and Dustin turned around and. . . slammed me in the face.” The slap left “enormous red finger marks on my cheek,” she said. Benton was in shock. Meryl, ever the professional, continued with the scene, which involved Joanna escaping down the elevator in the hallway outside the Kramers’ apartment. Later, as the camera captured her emotional goodbye, she heard Dustin, the Method man, attempt to provoke her by mentioning John Cazale (Streep’s boyfriend, who’d died the year before). Such was his warped approach to get under Meryl’s skin and elicit the performance that he wanted.

Meryl hardly needed Dustin’s help. She was angry. After Kramer, Dustin would never push her around again.

“It was overstepping,” she reflected in 2018, months after #MeToo exposed Dustin’s history of sexual misconduct and boorish behavior toward female colleagues. “But I think those things are being corrected in this moment. And they’re not politically corrected; they’re fixed. They will be fixed, because people won’t accept it anymore.”

“I finally yelled at her,” Dustin said. “‘Meryl, why don’t you stop carrying the flag for feminism and just act the scene!’”

Another unscripted moment was the restaurant scene where Joanna announces her intent to assume custody of Billy. The screenplay called for Joanna to break the news right away and then explain, “All my life, I’ve felt like somebody’s wife or somebody’s mother or somebody’s daughter—even all the time we were together, I never knew who I was.” However, Meryl wanted to say this before dropping the Billy bomb as part of her mission to humanize Joanna. Benton agreed, but Dustin was fuming.

“I finally yelled at her,” Dustin said. “‘Meryl, why don’t you stop carrying the flag for feminism and just act the scene!’ She got furious. That’s the scene where I throw the glass of wine against the wall and it shatters. That wasn’t in the script, I just threw it at her. Then she got furious again. ‘I’ve got pieces of glass in my hair!’ and so on.”

For the courtroom scene, Benton—who wrote the script and willingly tweaked it with Meryl’s input—asked Meryl to rewrite Joanna’s monologue on the witness stand. “I think I’ve written it as a man, not as a woman would say it,” he told her. “Take the speech, keeping the points that were made, but put it in a woman’s voice.”

When the time came, Meryl brought a legal pad and a page and a half of handwritten dialogue. Benton thought, Oh my God, what have I done? I’m going to lose a friend and two days of work. This is going to be awful. He braced for the worst. Then he read her revise, and—phew—it was about a third too long but perfect. Even better: he didn’t have to worry about hurting Meryl’s feelings or losing her as a friend. They trimmed the speech together, cutting two lines, and handed it to the script supervisor.

Action.

She nailed the first take, prompting a stunned silence from everybody in the room. Benton began to worry that Meryl would use up all of her powers because this was going to be a long day and he had much more footage to film, including reaction shots. Benton approached her and warned, “Meryl, please don’t. You’re new to this. Please don’t blow this early because there’s a lot.” He urged her to “save it for the close-up.”

Meryl didn’t listen. Take after take, she delivered her lines as if it were the first time she said them. “It was never mechanical,” says Benton. “After maybe the third or fourth time that she did it, I suddenly realized I was scared shitless of her. That control, and the depth, was unbelievable.”

Joanna was coming into her own but in a very different way than Meryl had on the set of Julia. Where the feminist, outspoken Jane Fonda proved an enthusiastic advocate for Meryl, the erstwhile Mrs. Kramer was a lonely island in uncharted seas, advocating for herself without another woman to help her. An excerpt of Joanna’s original speech, as written by Benton: “Don’t I have a right to a life of my own? Is that so awful? Is my pain any less just because I’m a woman? Are my feelings any cheaper?”

Meryl could let loose and play someone grittier than a supporting starlet who exists only to let the Dustin Hoffmans and the Robert De Niros and the Alan Aldas chew the most scenery.

Meryl doesn’t get enough credit for her writing skills. The way she tweaked Benton’s attempt, she toned down the theatrics and went straight for the emotional jugular, rendering an utterly sympathetic, discreetly feminist portrait of Joanna that endeared the character to skeptics predisposed to villainize her. “I was incapable of functioning in that home, and I didn’t know what the alternative was going to be,” she wrote. “So I thought it was not best that I take [Billy] with me… I was his mommy for 5 ½ years. And Ted took over that role for 18 months. But I don’t know how anybody can possibly believe that I have less of a stake in mothering that little boy than Mr. Kramer does. I’m his mother.”

She triggered Benton with the word mommy. And Dustin, up on his old tricks, triggered Meryl with the words John Cazale. He whispered them into Meryl’s ears and briefed her to look directly at him when Ted’s attorney says, “Were you a failure at the most important relationship in your life?”

She followed his advice, and, upon making eye contact, Dustin’s response touched the heart: he shook his head, ever so slightly, creating an interlude of tenderness between the foes—and letting Meryl/Joanna know that he didn’t think she had failed.

Meryl had given him something real to react to. And Benton, eager to keep the magic going, had Dustin repeat his micro-gesture so he could capture it on film.

It seemed as though Meryl, four movies in, was finally getting the hang of it. But the theater held a special place in her heart. There, she didn’t run the risk of losing what made her great. She could let loose and play someone grittier than a supporting starlet who exists only to let the Dustin Hoffmans and the Robert De Niros and the Alan Aldas chew the most scenery.

“Working on movies is very economical, clean, pared down,” she said in 1979. “You can afford to do so little. You don’t even have to be a good actor, or even an actor, to be effective in movies. But when you get a good actor, like Brando or Olivier, there’s a difference— when somebody takes a part by the throat and sings with it. My fear is that in doing so little, I will not be able to do what I do on stage, which is to be brave, to take the larger leap.”

__________________________________

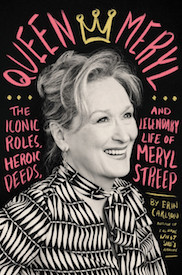

Excerpted from Queen Meryl by Erin Carlson, published on September 24, 2019 by Hachette Books, a division of Hachette Book Group. Copyright 2019 Erin Carlson.

Erin Carlson

Erin Carlson is a culture and entertainment journalist, and the author of three Hollywood history books, including I’ll Have What She’s Having and Queen Meryl. Her work appears in many publications, including Vanity Fair, Town & Country and her Substack newsletter, You’ve Got Mail. She lives in San Francisco.