Why you should read Howard Zinn’s Artists in Times of War now.

“There are certain historical moments when learning is more compressed and intense than others,” wrote Howard Zinn, a month after 9/11. The historian was writing in a moment of tremendous, escalating violence, and he sensed more death and destruction looming. Zinn could hear a familiar melody in the drum taps coming out of the White House, from the pages of the New York Times, and in the academic institutions where he taught. His line about certain historical moments has been ringing in my ears. Compressed learning continues to exact a horrid cost.

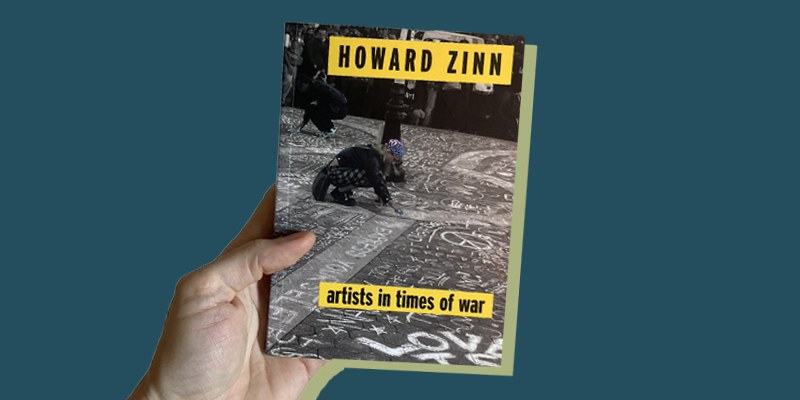

The line comes from Artists in Times of War, Zinn’s slim collection of four essays about dissent in America. There’s a piece on anti-war artists, one on Emma Goldman and her anarchism, an essay on the stories that Hollywood never tells, and a celebration of pamphleteering in America. The collection was published by the excellent Seven Stories Press, and is a bracingly quick read—you can read it twice in an afternoon, and you should.

This book is exactly the kind of radical pamphlet Zinn cites as an essential American form: polemical ideas, plainly written, and published in simple, short volumes that are easily shared and easily hidden away. Zinn’s tetraptych are full of his theories of historical change, illustrated by his subversive and questioning mode of history that always seeks the underdog heroes and movements. Even the fights we accept as “good” are reversed; Zinn tells us about Union soldiers razing native villages in Colorado mere days after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, and about Shays’ Rebellion, when the rich in Boston raised an army to put down Revolutionary War veterans the same year the Constitution was ratified.

The historical figures he writes about will be familiar to anyone who knows his work, artists like Mark Twain, Langston Hughes, and Joseph Heller, as well as radicals like Bartolome de la Casas, Mother Jones, and Emma Goldman. Zinn’s spare and striking specifics are always memorable, like the wonderful detail in his second essay about Ben Reitman, an anarchist, doctor for the poor, and Emma Goldman’s lover. Reitman was beaten up and branded with “I.W.W.” on his butt while defending free speech in San Diego. But the scarlet letters of the International Workers of the World got a different response than intended: Reitman, Zinn writes, “was the kind of guy who later, when he appeared on a platform, would suddenly turn his back to the audience and pull down his pants to show them what had been done to him, which horrified Goldman.”

But it’s the title essay from Artists in Times of War that has stuck with me, adapted from a speech given in October 2001, when American retaliation had already killed more people than died on September 11th, and the march towards wider war was beginning to feel inevitable.

Zinn’s goal is to dismantle the idea that any of us should count our voices out, and highlight the best of American dissent. The best artists from our past are always citizens and human beings, he says, rejecting the framing that you “have to be professional,” a word “that limits human beings to working within the confines set by their profession.”

Zinn again:

The lawyer says, “It’s not my business.” The businessman says, “It’s not my business.” And the artist says, “It’s not my business.” Then whose business is it? Does that mean you are going to leave the business of the most important issues in the world to the people who run the country? How stupid can we be?

Zinn’s language is so plain, that I can almost imagine him speaking to a crowd of children. But his tone isn’t condescending, and he’s not dumbing anything down. He’s writing about things that are so evident and important, that there is no other way to state them but simply. “All of us, no matter what we do, have the right to make moral decisions about the world,” he writes.

And this right to dissent, on moral grounds, is something that Zinn rightfully pinpoints as essential to America’s self-conception. Our foundational text, America’s biggest historical pamphlet, undercuts the idea that you should have any faith in government: “The Declaration of Independence says that governments are artificial creations,” Zinn writes. Our values should lie elsewhere, with the people and ideas that are worth defending. And should never forfeit the right to make moral decisions when the form of a government becomes destructive to self-evident truths.

Over and over in his invocation of great socialists and anarchists of the past, Zinn reminds us to act in solidarity: “Today everybody is talking about the fact that we live in one world; because of globalization, we are all part of the same planet. They talk that way, but do they mean it?” There is nothing more hollow than being told to disregard someone because of where they are or where they came from.

In these essays, Zinn brings up history not to shock us, but to ask us what we value. This is our history, he asks, are these things done in our name a source of pride? The forthrightness of Zinn’s prose is a bulwark against those familiar arguments that you need to be an expert to speak up. These are hard, complicated, nuanced issues, they say. But Zinn reminds us that the simplicity of a moral argument is everyone’s right: “If we are going to be anything, if there’s anything an artist should be—if there’s anything a citizen should be—it’s honest.”

When we say no to genocide, to war, to oppression, we are doing what artists, radicals, and historians like Zinn have done forever: told each other and those in power that there is something deeply wrong and we won’t tolerate it. It’s an act of defiant optimism in the face of horror. “The artist needn’t apologize,” Zinn writes, “the artist is telling us what the world should be like, even if it isn’t that way now.”

James Folta

James Folta is a writer and the managing editor of Points in Case. He co-writes the weekly Newsletter of Humorous Writing. More at www.jamesfolta.com or at jfolta[at]lithub[dot]com.