Why Writers Shouldn’t Wait for Permission to Create the Stories They Want

James Hannaham on Uncensored Reading, Salacious Novels, and Marginalized Authors

I’ve never really understood the idea of writers, especially women and minority writers, waiting for “permission” to write what we want, when we want. How did the process of regurgitating terrible first drafts from a brain into a laptop or a notebook become something anyone needed to ask permission to do? I have had some luck and success in publishing, but I never assume that I’m going to show anyone what I’ve written. We have an extremely limited time on the planet—far less to devote to writing—so why prevent ourselves from working? Isn’t that what the murky entities who deny us permission want? Our obedience? Our silence?

I would say that it has never occurred to me to ask for permission, but that’s not exactly true. Sometimes I realize that I should have asked for permission. Which is different. Our first notions of permission often come from our parents and/or our religions with regard to most things, but especially our reading material. I got very lucky. For reasons I can’t exactly pinpoint (it was the 1970s? she had artistic tendencies?), my mother, a divorced Black woman from Georgia living in the suburbs of New York City, chose not to censor her children’s reading.

There were boundaries, of course. We knew not to read pornographic magazines at the dinner table. And she was not against certain types of censorship. She once went on a crusade to have the racist children’s book Little Black Sambo removed from the kids’ section of our library, a battle she won. Other types of censorship she did not believe in. On our bookshelf at home, she kept titles like Joyce’s Ulysses and Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal next to Sammy Davis Jr.’s autobiography Yes I Can and The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

My mother’s peers sneered at her “permissive” parenting because she allowed us to read freely. Mom had also stopped going to church, or making us go, another way in which she brought on controversy and isolated our family from the community, but also liberated us from certain expectations about piety. Turning her back on the church didn’t trouble her at all; she had never cared what others thought of her. Whenever someone told her she couldn’t do something, she would smile and say, “Watch me.”

Was all this permission a bad thing? In second grade, I got called into the principal’s office for writing something on my classwork that suggested I knew that the word “intercourse” had a sexual connotation. I was a little baffled. Why would they reprove me in school for knowing things? My takeaway was just that I shouldn’t display that kind of learning in school. Instead I wrote a series of graphic, juvenile stories about people I disliked, which I titled When Nightfall Comes, and hid them in a dresser drawer.

When I graduated to the adult section of the library, I devoured dirty books like other kids ate bologna sandwiches. I remember clearly many of the risqué books and records (which we could also take out from the library) that blew my young mind: Little Birds by Anaïs Nin, The Olympia Reader, Iceberg Slim’s Pimp: The Story of My Life, Justine by the Marquis de Sade, Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth, Robert Gover’s outrageous One Hundred Dollar Misunderstanding, an anthology of gay plays called Boy Meets Boy, Naked Lunch, The Wild Boys, Queer, and Cities of the Red Night by William S. Burroughs, and a super-salacious novel called Les Onze Mille Verges by Guillaume Apollinaire that he denounced after its publication.

My mother caught hell for her openness, but uncensored reading may have saved my life.

My voracious appetite for the inappropriate went well beyond fiction, too—I sought out books about the psychology of sex, including its apogee, Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis, but also Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Shere Hite’s Hite Report diptych on female and male sexuality, and volumes by Gay Talese (Thy Neighbor’s Wife) and Karen Horney, whose names alone sounded racy. To say nothing of outlandish comedy albums by the likes of Monty Python, Richard Pryor, Tom Lehrer, and Redd Foxx, to name a few. (My local public library was remarkable.) If there was a through-line to most of my early cultural experience, it was, as Lehrer exclaimed, “Smut! Give me smut and nothing but!”

Having read and experienced all of this literary lasciviousness in an unsupervised way, with no context whatsoever, long before seriously considering becoming a writer is, I think, what gave me permission to do almost anything I could imagine once I started. There’s not much to recommend the Marquis de Sade, perhaps the least inhibited scribe ever, whose scenes of amoral mayhem remain as shocking today as they did in the 1700s. Among other things, he wrote about adults exploiting children for sex, but he also had the courage of his convictions, let’s say. He meant to live as he wrote, and spent many years in prison just for being an unbelievable libertine, writing not so much for money or publication, but just to titillate himself in the clink. Not the most honorable career.

However, if you’ve read Sade, Burroughs, and Psychopathia Sexualis and then turn to your own fiction, you will never feel your work goes too far in whatever direction you take because you’ll know exactly what “too far” looks like. I’ve never thought of this as “permission” exactly, more like a conveniently distant benchmark. My unbridled reading kept me aware that some crazy precedents had already been set centuries ago. Dozens of European perverts had created work so far beyond the fringe that nobody in today’s world of publishing had a shred of moral authority to enforce decorum.

And while Sade remains reprehensible, many classics were denounced as filth in their day—Madame Bovary, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, The Awakening—it started to seem to me that a book couldn’t possibly be any good if it didn’t scandalize everyone. So I thought, Okay, let’s do this. One of the first stories I wrote was about a gay Black man who accidentally strangles a closeted Republican senator during rough sex.

Which brings me to America. Nothing gets Americans as twisted as racial issues and queer sexuality. In that sense, my desire to provoke readers aligned perfectly with my identity. This, I believe, is what James Baldwin was talking about when he said he felt he’d won the jackpot. In the United States, our press is comparatively free—journalists and whistleblowers who leak tightly held government secrets can get jailed or exiled, but fiction writers, knock on wood, are mostly left alone, because it’s assumed that we don’t matter. You have to work hard to be an American dissident. In many other countries, I might fear for my life given the subject matter I gravitate toward. Stateside, I sometimes forget that people might consider anything I’ve written controversial.

That publishing is dying for diversity must not go without saying. While this needs to be addressed, it should also encourage anyone nonmale, nonwhite and/or nonstraight to know that publishing needs you more than you need it. And frankly, you’re reading the industry all wrong if you haven’t noticed that people in publishing are basically a hoard of sex-mad nerds who are totally bored with having to read gigantic piles of amateur work that plays it safe. Despite appearances, they’ve read Sade. They know what Lord Byron and the Shelleys got up to.

And at this point in time, the entirety of US mainstream publishing is finally feeling the embarrassment they should have felt for years about how many marginalized groups they’ve, well, marginalized. You should also take heart that even as the Big Five publishers gradually contract into the Big Two, independents and self-publishing have always provided a haven for renegade authors—The Grove Press in particular printed a lot of transgressive writing and fought the legal battles that enable you to write without boundaries in America, at least.

My mother caught hell for her openness, but uncensored reading may have saved my life. Because of my ability to explore, I knew about AIDS even when it was called GRID (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency), long before I became sexually active, before I had admitted to myself that I was queer. And I was terrified, but informed. On top of all the explicit fiction, I also knew about safe sex practices.

People commonly speak about free speech in political terms, but it’s just as important to consider how devastating it can be to conceal information about sex and sexuality. It’s possible that that kind of censorship contributes as much, if not more, to the feeling that we don’t have permission to express ourselves.

__________________________________

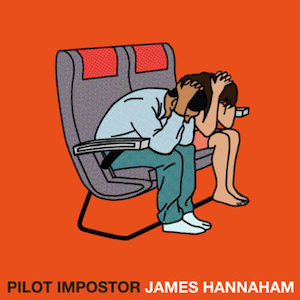

Pilot Imposter is available from Soft Skull Press. Copyright © 2021 by James Hannaham.

James Hannaham

James Hannaham was born in the Bronx, grew up in Yonkers, New York, and now lives in Brooklyn. His most recent novel, Delicious Foods, won the PEN/Faulkner and Hurston/Wright Legacy Awards. He teaches at the Pratt Institute.