Why We Should All Be Reading English Novelist Kay Dick

Lucy Scholes on the Life and Writing of the Underappreciated Author of

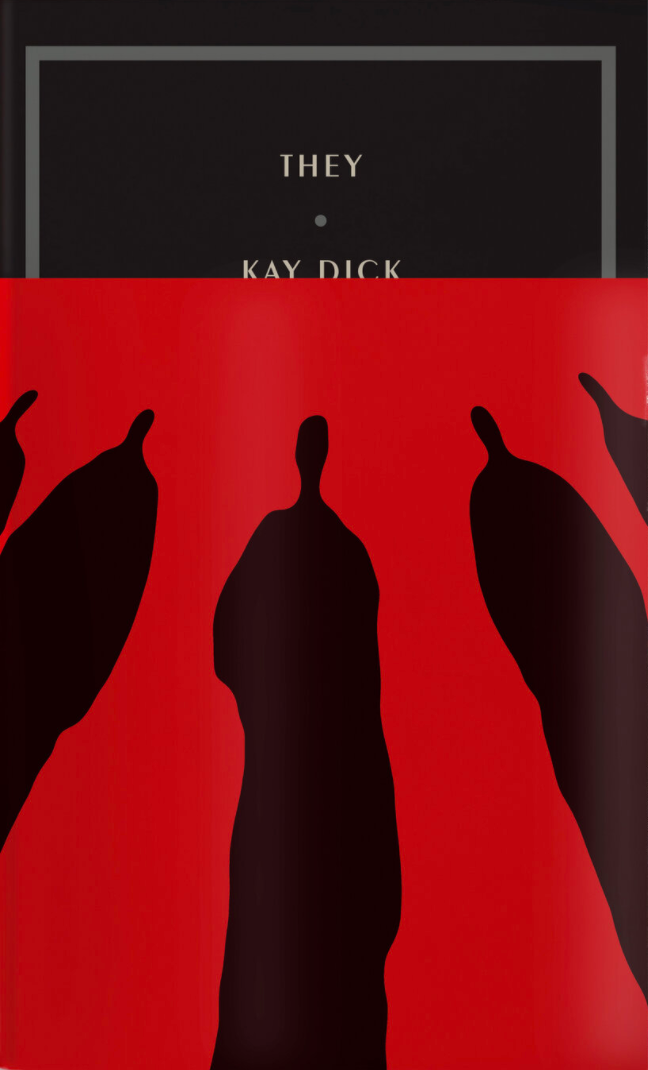

When They was first published in 1977, it surely took readers by surprise. Not just because of the eerie, haunting power of the narrative therein, but because it’s a complete anomaly in Kay Dick’s oeuvre; a surreptitious late-career aberration, the genesis of which is unclear, and whose strangeness never seeps into what she wrote after.

Compared to Dick’s earlier novels—By the Lake (1949), Young Man (1951), An Affair of Love (1953), Solitaire (1958) and Sunday (1962), all of which are tales of romantic or familial entanglements set against the backdrop of urbane European settings the writing of which was often praised as “Proustian”—it seems the work of an entirely different writer. Stylistically and tonally, They is much closer to the works of experimental British writers Ann Quin—is it just a coincidence that one of the characters is named “Berg,” the same as the eponymous protagonist of Quin’s 1964 debut?—Christine Brooke-Rose, and Anna Kavan.

Dick greatly admired her good friend Brooke-Rose’s avant-garde works, especially Out (1964)—a “race reversal” novel set in the aftermath of a catastrophic event that leaves white people suffering from radiation poisoning, but Black people unscathed—which Dick, writing in Friends and Friendship (1974), her collection of interviews with fellow authors, described as “powerful, sinister, near prophetic . . . Orwellian fiction.” Ice (1967), Kavan’s enigmatic, almost psychedelic final novel—in which a man pursues a silver-haired woman across a snowy, post-apocalyptic wasteland—reads like a sinister dream sequence, a description that could also be applied to the unsettling, cryptic chapters of They.

Interestingly, both Brooke-Rose and Kavan switched registers following episodes of significant upheaval in their lives. The former survived a near-fatal kidney operation in 1962, while Kavan’s midlife reinvention has been much mythologized: “Once a wholesome young English housewife who wrote conventional women’s fiction, so the story goes, in her thirties she was confined to an insane asylum and emerged as a chic, emaciated bottle-blonde heroin addict, wielding a bleak and anarchic new literary voice,” summarized the critic Emma Garman.

Whether They was the result of something similar in Dick’s life, we can’t be sure. She certainly underwent a period of intense bereavement and loss in the 1960s—this included the breakdown of a relationship, followed by the death of a lover who killed herself, an experience Dick later wrote about in her final novel, The Shelf (1984), and a suicide attempt of her own, which she talks about in the autobiographical essay included in Friends and Friendship (1974). These experiences could also explain her particular interest in “Coping with Grief,” the 1975 Sunday Times article that she takes such pains to credit at the beginning of They.

What we do know for sure, though, is that in Friends and Friendship Dick points out that what makes Brooke-Rose’s most recent writing “so remarkable” is its “divergence . . . from her earlier more fashionable novels.” Perhaps her admiration for such an astonishing volte-face—combined with the impact of the recent emotional disturbances she’d undergone—inspired Dick to try something similar herself. After all, she writes “Hallo Love,” the final chapter of They, only a year later, in March 1975.

“It is an extremely courageous act to be a writer, painter, composer, because you are out on your own, in limbo, totally unprotected, not much encouraged.”

Aptly, much of the novel’s power lies in its various mysteries. There’s the enigmatic “They,” “omnipresent and elusive,” as Philip Howard describes them in his review in the Times, dangerous and violent, but also strangely vacant and automaton-like. That they’re an informal multitude, rather than a government-sanctioned group like Ray Bradbury’s book-burning “firemen” in Fahrenheit 451 (1953) or George Orwell’s all-pervading government surveillance in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), makes Dick’s creations all the more ominous. Their initial strength lies not in official mandates, but rather in the swell of their ever-increasing numbers. Rarely distinguished as individuals, they’re situated in stark contrast to the narrator and the other artists, intellectuals and craftspeople.

There is a certain degree of inscrutability here too. In neither naming the narrator, nor revealing their gender, They is Dick’s most radically androgynous book. In a 1986 interview with Kris Kirk in the Guardian, Dick explained that the “overall tone” of the personal relationships depicted in her books is always bisexual, as this is how she herself identified. Although sexually attracted to both men and women, she described there being “something extra”—“this love, this emotion”—in her relationships with the latter, but she was in any case uninterested in binaries. “I have certain prejudices and one of them is that I cannot bear apartheid of any kind—class, colour or sex,” Dick continues. “Gender is of no bloody account.”

So who was this wonderfully outspoken, confident woman? The more I discover about her life, a figure emerges who is just as singular and trailblazing as her remarkable novel. Dick was born to an unmarried mother in London in 1915. “She must have had great courage,” writes Dick in Friends and Friendship, “because illegitimacy in the First World War was a very unpleasant business to be mixed up with, especially for a woman brought up in a reasonably privileged fashion.” Her mother had already broken with her more respectable family before she became pregnant with Dick, instead making her home among the bohemian society that revolved around London’s famous Café Royal—“artists, actresses, demi-mondaines—penniless the lot of them,” as Dick describes the crowd—and this is where Dick’s mother immediately returned when she was discharged from the hospital with her newborn daughter. After such a “baptism”—Dick received no religious ceremony, just the “toasts and blessings” that were exchanged by the Royal’s patrons over her head on her first night on earth—it’s “small wonder that I have a taste for café life,” she explains.

The childhood that followed was cosmopolitan and distinctly European; travels on the Continent were de rigueur. From the age of four, she and her mother were kept by her mother’s lover, a wealthy Swiss man who eventually left his wife and married Dick’s mother when Dick was seven, thus transforming their “stateless merriment” into “middle-class respectable living.” A two-year stint at an expensive English girls’ boarding school proved unpleasant, so Dick was sent to a coed day school in Geneva instead (she lodged with a local family), an experience she found much more agreeable, and thereafter she finished her education at the Lycée Français de Londres in South Kensington.

Dick recalls having known, since the age of ten, that she wanted to become a writer. “There was never any doubt in my mind,” she explains in Friends and Friendship. But as her stepfather had lost some of his money by the time she came of age, sitting in an ivory tower wasn’t an option. Not that the prospect of earning her own living perturbed her. Dick began her “career in the book trade,” as she puts it, and thus found herself “back with those penniless bohemians of the Café Royal.”

When talking to Kirk, she recalls frequenting the gay bars and cafés of London’s Soho, which she and her bisexual friend Tony gadded about together, both wearing cloaks and carrying walking sticks. “I ran to the artists and writers we’d now call the Alternative Society,” she explains. “We were very politically motivated, the Spanish Civil War was our Mecca.” After various editorial jobs, she became—at the tender age of twenty-six—the first woman director in English publishing, at P. S. King & Son, after which she was made the editor (under the pen name Edward Lane) of the short-lived but acclaimed literary periodical The Windmill: it was she who commissioned and then published, in the magazine in 1946, Orwell’s now famous essay in defence of P. G. Wodehouse.

The Dick I’ve discovered is an utterly beguiling woman, one who, although undoubtedly spiky, produced a large body of important work.

During the mid-20th century, Dick was at the very heart of the London literary scene. A list of the guests regularly entertained by her and her partner, the novelist Kathleen Farrell, at their Hampstead home at 55 Flask Walk—they lived together from 1940 to 1962—includes a host of successful and popular writers of the era, including C. P. Snow, Pamela Hansford Johnson, Brigid Brophy, Muriel Spark, Stevie Smith, Olivia Manning, Angus Wilson, and Francis King.

For a woman who regarded her friends so highly, the obituary that ran in the Guardian on the occasion of Dick’s death in 2001, age 86, did her an unforgivable disservice. Its author, the writer and journalist Michael De-la-Noy, claims that Dick “expended far more energy in pursuing personal vendettas and romantic lesbian friendships than in writing books”—a cutthroat accusation that smacks of a vendetta all its own. Unbelievably, he then goes on to describe Dick as a failed artist, “a talented woman bedeviled by ingratitude and a kind of manic desire to avenge totally imaginary wrongs.” Although this was wild enough to grab my attention when I first came across the obituary, it soon became clear, after only the most cursory of further investigations, that De-la-Noy’s defamatory assertions couldn’t be further from the truth.

“Here is a writer who respects human beings even in their pettiness or confusion; who regards each of them as a worthy object of study and even tenderness, and who devotes as much space and care to the description of what one might call a thoroughly trivial person as to a creature of heroic design,” wrote the Sphere’s critic Vernon Fane in his review of Dick’s second novel, Young Man. Sunday—a loosely autobiographical story about Dick’s childhood and her relationship with her mother—goes even further in demonstrating its author’s psychological astuteness; reviewing the novel for the Daily Telegraph, Peter Green extolled Dick’s “positively Proustian nose for significant nuances of behaviour.”

So uncharitable were De-la-Noy’s awful charges, the Guardian received letters of rebuttal from many of Dick’s closest friends. The writer of one of these, the author and journalist Roy Greenslade, who was a neighbour of Dick’s in Brighton for thirty years, was adamant that any of the “silly feuds” she indulged in were far “outweighed by her acts of kindness and generosity towards her friends, especially young people. She encouraged almost every youngster she ever met to write, lauding their efforts to the skies in public, while offering helpful criticism in private.” The author Michael Ratcliffe also defended his friend passionately: “Kay was funny, encouraging and generous,” he writes. “The young loved her, and she them.” This side of her character is completely absent in De-la-Noy’s obituary, but clearly it’s one of the things that those who knew Dick valued most highly. As Greenslade continues:

She was, in fact, a most perceptive critic, preferring too often to spend her time reading the works of others rather than writing herself. Few people read as much as Kay. “Darling, I’ve just been rereading Scott,” she once said. “He was brilliant.” I asked: “Which novel?” “All of them,” she replied, without the least sign of boasting. Her other great talent lay in introducing people she met to her wide network of friends and contacts. She loved our children, helped them, made them laugh, made them think. Both of them, like my wife and I, benefited from knowing the lady with the cigarette holder and the succession of dogs along the terrace.

Pertinently though, Ratcliffe expresses his confidence that “[p]osterity will place her work.” And now, twenty years on, he’s been proved right.

*

Little did I know, when I first wrote about They for the Paris Review Daily in August 2020, that within less than two years I would have the chance to bring it back into print with McNally Editions. The Dick I’ve discovered is an utterly beguiling woman, one who, although undoubtedly spiky, produced a large body of important work while also living an extremely full, free life in the company of many dear friends. Pierrot (1960), for example, her study of commedia dell’arte, is considered something of a definitive work on the subject.

Dick was a most perceptive critic, preferring too often to spend her time reading the works of others rather than writing herself.

Then, during the fifteen-year gap between Sunday (1962) and They (1977), she published two absorbing volumes of literary interviews: Ivy and Stevie (1971) and the aforementioned Friends and Friendship (1974). Writing in the Times in 1974, A. S. Byatt declares that the former “would always be required reading” for anyone interested in either of its subjects, Ivy Compton-Burnett and Stevie Smith.

Dick’s later obituary in the same newspaper attributes her success as an interlocutor to the fact that she was a woman of “sympathy and perception,” one who’d “persuaded two naturally reticent women writers . . . to reveal more about their inner lives than they had ever done to anyone, except obliquely through their writings.” My great hope is that this reissue of They will not only reintroduce this brilliant novel to the world, but that it will also go some considerable way to setting the record straight when it comes to its author’s character and achievements. As Paul Bailey avowed in the Observer, her autobiographical portrait in Friends and Friendship reveals “a most interesting and complex woman, a woman worth reading about.” He describes Dick’s writing as “poignant, honest, occasionally catty, and—finally—extremely sympathetic.”

Through the 1940s and 50s, although clearly already an accomplished editor—Orwell, for example, inscribed her copy of Animal Farm (1945) with “Kay—To make it and me acceptable” in recognition of her editorial work—as a writer, she was still learning her craft. But it’s in the latter half of her career—by which point Dick had left London and moved to Brighton, and had campaigned tirelessly for the Public Lending Rights Bill, which, when it was passed in 1979, finally allowed authors to receive payment for the free loan of their books through the UK public library system—that she comes into her own as a novelist: first with They, and thereafter The Shelf, which is written as a letter to Francis King, and relates the story of the brief affair Dick had with a married woman in the early 1960s—not long after the breakdown of her relationship with Farrell—and this lover’s tragic suicide. The events described are true, Dick tells Kirk, before adding mischievously, “Though I shall deny it, of course.”

There’s truth to be found in They too, despite the distractions of its dystopian, experimental elements. Yes, it reminds us of the value of art and culture, but it’s also a book about the importance of friends; it’s a fictional exposition of this impassioned cry, in Friends and Friendship, for what Dick most holds dear: “I shall never wish to stop rereading the books I love, looking at paintings, listening to music, and, more than that, I should wish to know my friends forever.”

Like any strong allegory, They can be read many ways—as a straightforward satire, a sequence of vividly-drawn nightmares, even a metaphor for artistic struggle—but above all, it’s perhaps best read as a plea for individual and intellectual freedoms made by an artist who refused to live by many of society’s rules. As Dick herself reminds us, “it is an extremely courageous act to be a writer, painter, composer, because you are out on your own, in limbo, totally unprotected, not much encouraged, driven only by some inner conviction and strength, and the discipline is yours alone.”

______________________________________

From Lucy Scholes’s afterword to They, by Kay Dick. Available now from McNally Editions.

Lucy Scholes

Lucy Scholes is a senior editor at McNally Editions, and writes for The Independent, The Times Literary Supplement, The Observer, BBC, The Guardian, and is a columnist for The Paris Review.