Why We Have Police: Race, Class, and Labor Control

Philip V. McHarris Traces a Line Through American Chattel Slavery, Reconstruction, Civil Rights, and the “War on Drugs”

Dominant power structures have institutionalized the idea that police are the only legitimate providers of public safety—which subsequently justifies their attempts to monopolize the use of violence. For most of history, however, police were not seen in that way. Rather, police were often considered as violent tools serving the interest of those in power, something that has remained true for many communities disproportionately targeted by police violence. Police are said to be the stewards of public safety, but across the country policing emerged as a tool of racial and class domination and control. Over time, we have seen that policing has been centered on maintaining the status quo, which has been shaped by white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism. The police violence we see throughout the country in the present is not a fluke, or aberration. The criminal-legal system today is not broken—it is operating exactly as it was designed: a violent tool of race and class control.

Policing, in various forms, has existed since colonialism and slavery in the United States. The formality, organization, and legitimacy of the police force has changed over time, but the institution of police, both when it was invented and as it exists today, is an apparatus to enforce the agenda of the state and coercively control the nation’s citizens. As Alex Vitale articulates in The End of Policing, “While the specific forms that policing takes have changed as the nature of inequality and the forms of resistance to it have shifted over time, the basic function of managing the poor, foreign, and nonwhite on behalf of a system of economic and political inequality remains.”

The first organized policing entities began as slave patrols in the South. Slave owners and local civilian officials paid full-time officers to prevent slave revolts. Slave patrollers would patrol private property and public space to ensure that slaves were not carrying any weapons or fugitives, conducting any meetings, or gaining literacy. Officers also patrolled the roads to catch any enslaved people who attempted to escape to the North. Although a majority of these slave patrols dominated rural areas and were loosely organized, urban patrols such as the Charleston City Guard and Watch that began in 1783 became increasingly professionalized. With the rise of industrialization, enslaved African Americans had to work in places far outside their owners’ property, so there were large numbers of unaccompanied enslaved people around the city. Officers were viewed as even more necessary to supervise, monitor, and inspect slaves who worked in these urban areas.

Policing, in various forms, has existed since colonialism and slavery in the United States.After the abolition of slavery, slave patrols no longer existed, but racialized policing continued. Systems of formal policing became expanded in small towns and rural areas and were used to suppress, intimidate, and control the newly freed Black population and force them into convict leasing and sharecropping. No longer prioritizing the prevention of rebellions, the police enforced laws that outlawed vagrancy in order to criminalize and force Black people into convict leasing through the sharecropping system—which maintained exploitative labor conditions consistent with those under slavery. Officers also routinely enforced poll taxes and checked proof of employment for any Black person on the road. During the Jim Crow era, police often enabled and worked with white supremacist vigilantes such as the Ku Klux Klan to maintain social, political, and economic racial hierarchies. Meanwhile, Northern political leaders also feared the northern migration of newly freed rural Black populations who were viewed as inferior in every aspect. As a result, Northern cities established segregated areas and utilized police officers to contain Black people in these spaces. In both the North and the South, the police employed brute means to impose geographical, social, and political limitations on Black communities.

Just as the state utilized the police force to maintain the inferior position of enslaved people and later freed African Americans, policing in the North began as informal, privately funded night-watch patrols to control working class immigrants and growing unrest among the industrial working class. Northern cities experienced an influx of immigrants and rapid industrialization, which instilled a sense of fear and resentment amongst white elites. They viewed Irish and other working-class immigrants as uneducated, disorderly, and politically militant. Labor strikes and riots broke out, inducing fear and anxiety and demands for the preservation of law and order. Although the informal night watch system was intended to block looting and labor organizing, they failed at preventing them, which resulted in the emergence and expansion of formalized, public policing to protect the interests of property and business owners. The creation of the police enabled enforcement of morality laws, such as restrictions on drinking. However, the early urban police were openly corrupt, as they were often chosen based on political connections and bribery. Qualifications to become a police officer did not entail formal training or passing civil service exams. Political parties also utilized them to suppress opposition voting and to spy on and suppress workers’ organizations, meetings, and strikes.

Because of the high degree of police corruption, business leaders, journalists, and religious leaders united and exposed the corruption of the police beginning in the early 1900s. In response to the pressure, policing became increasingly professionalized through civil service exams and centralized hiring processes, training, and new technology. Management sciences were also introduced. Reformers such as August Vollmer, who drew his ideas from his experiences in the US occupation forces in the Philippines, also implemented police science courses, which introduced new transportation and communication technologies, as well as fingerprinting and police labs.

Police reformers of the twentieth century paved the way for the increasingly intertwined relationship between standardized technology, policing, and surveillance. Police militarization—where police adopt military strategies, tactics, and tools in routine policing—began to increase in intensity in the early twentieth century as a result of imperial feedback, where police expanded their infrastructural power using militarization models, borrowing tactics, techniques, and organizational templates from America’s imperial-military regime developed to conquer and rule foreign nations. Imperial feedback paved the way for police to adopt strategies and tactics used by the imperial military to control colonial subjects abroad to control racial and class minorities in the United States, such as African Americans and Indigenous communities.

Just as the state utilized the police force to maintain the inferior position of enslaved people and later freed African Americans, policing in the North began as informal, privately funded night-watch patrols to control working class immigrants and growing unrest among the industrial working class.The United States also employed colonial policing through the Texas Rangers, which were formally established in 1835. Texas Rangers were hired to protect the interests of newly arriving white colonists under the Mexican Government and later under the independent Republic of Texas. The Texas Rangers hunted down native populations who were accused of attacking white settlers. Rangers also facilitated white colonial expansion by pushing out indigenous Mexicans through violence, intimidation, and political interference. Mexicans and Native Americans who resisted were subject to beatings, killings, intimidation, and arrests. Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, local and state elites also relied on Rangers for political suppression of Mexican Americans’ suffrage rights and worked to subvert farmworker movements through similar tactics. Utilizing intimidation, they prevented voter rallies and threatened opposing candidates and their supporters. After organized resistance, communities pushed back against the Texas Rangers, which ultimately helped to pave the path for civil rights for Mexican Americans.

The early forms of policing across the nation served to maintain the interests of the dominant class of white elites. By characterizing newly freed Black Americans, the working class, and incoming immigrants as deviant, morally inferior, and uneducated, both state and local police forces used brute force to ensure that they remained in their perceived inferior positions.

At the turn of the twentieth century, political leaders of the United States radically changed the organization and responsibilities of the police department. For much of history, the general public perceived the police as illegitimate and riddled with corruption. Reformers in the 1920s and ’30s attempted to rid departments of organizational corruption and to decouple their close ties with political elites. Instead, they emphasized that the role of police departments was in crime control and arrest. Changing expectations of police led to organizational changes, in which police departments took on a more centralized, bureaucratic, paramilitary organizational structure. Inevitably, the reform era led to police professionalization that further cemented their power and allowed them to do more unchecked harm. These shifts led to changes in how a police department’s success was measured, focusing increasingly on higher arrest rates and “efficiency” determined by rapid response time to emergency calls. By the 1950s these priorities were having devastating impacts on marginalized communities of color, beginning with Black communities.) Scholars have long shown that poverty and disadvantage, shaped by centuries of structural racism, are closely related to levels of police violence and harm in neighborhoods across the nation.

During the 1960s, a large number of the urban rebellions that rocked the nation were directly prompted by incidences of police brutality. At the same time, the War on Crime and the Law Enforcement Assistance Act provided police with increasing amounts of resources and also helped to create a climate that legitimized police as viable “crime stoppers,” even though the expect police even have on what is referred to as crime is largely inconclusive.

The early forms of policing across the nation served to maintain the interests of the dominant class of white elites.The Civil Rights and Black Power Era saw an incredibly violent, repressive policing and carceral backlash. The period was a time of widespread activism—including the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the antiwar movement, and the Black Panthers. For groups like the Black Panthers, which began in Oakland, California, that activism looked like both protecting Black communities from police violence and launching a wide variety of initiatives ranging from free breakfast programs for children to health clinics and ambulance services.

On the local, state, and federal levels, police engaged in surveillance, violent repression, and criminalization of nationwide protest and dissent against the US government. The violent repression of Black movements through COINTELPRO epitomizes the development of increasingly violent surveillance tools and police violence. One notable example of COINTELPRO’s violent suppression of Black activists was the case of Fred Hampton, who was murdered in his home during a raid conducted by the Chicago Police Department and the FBI. Many other activists during this period were jailed, injured, and killed by local, state, and federal law enforcement.

President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Crime and creation of the Law Enforcement Assistance Act expanded the push towards empowering local law enforcement by legitimating the police as stewards of public safety. The 1965 Law Enforcement Assistance Act flLEAA) authorized the US Attorney General to make grants for the training and expansion of state and local law enforcement personnel.1# As the president told Congress in 1966, “The frontline soldier in the war on crime is the local law enforcement officer.” The LEAA subsequently created the first federal funding stream for local policing exports. At the height of an era that professionalized policing, Johnson’s financial support at the federal level and valorization of local police reinforced a paradigmatic shift toward the perception that local law enforcement served as the only legitimate gatekeepers to public safety.

The coming decades would set the stage for the mass incarceration of today. The emergence of police strategies—coming out of Johnson’s War on Crime—specifically aimed to violently police and punish Black people, poor people, and marginalized communities. These criminal-legal exports included the War on Drugs, War on Gangs, and the criminalization of poverty, homelessness, and survival—such as sex work. During the 1970s and onward, police developed and expanded tools such as hot-spot and problem-oriented policing, stop-question-frisk, investigatory traffic stops, surveillance devices like wiretaps, and data-driven police tactics as new standards. Moreover, police increasingly became involved in immigration enforcement and detention and deportation proceedings. These five decades filled jails with Black people, as well as poor people and people from other marginalized communities. From 1983 to 2012, the United States spent $3.4 trillion more on the criminal justice system as a result of mass incarceration, criminalization, and policing.

__________________________________

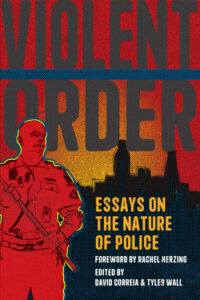

This essay “Disrupting Order: Race, Class, and the Roots of Policing” by Philip V. McHarris appears in Violent Order: Essays on the Nature of Police. Haymarket Press, edited by David Correia and Tyler Wall, with a foreword by Rachel Herzing. Used with permission of Haymarket Books.