Why We Feel So Compelled to Make Maps of Fictional Worlds

Lev Grossman on the History of Cartography in Sci Fi,

Fantasy, and More

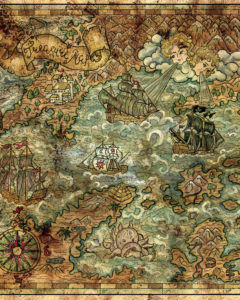

In 1665, a German Jesuit and polymath named Athanasius Kircher published an eclectic scientific treatise called Mundus Subterraneus. It included, along with a natural history of dragons and a diagram of the Earth’s many unknown interior chambers, a convincingly detailed map of “Insulae Atlantidis”—the island of Atlantis.

What strikes you about it most is the confidence. There’s nothing vague or sketchy about Kircher’s Atlantis, it’s highly specific. Situated square in the middle of the Atlantic, and colored a creamy yellow, it’s shaped like an upside-down Africa, with six wiggly rivers and two east-west mountain ranges. It’s like Kircher’s been there personally—this isn’t terra incognita, it’s thoroughly cognita. However firmly one grasps the fact of Atlantis’s nonexistence, Kircher’s map still triggers an instinctive longing, an invitation au voyage that whispers: Quit your job, throw it all over, and go to Atlantis right now!

It’s a magic trick of sorts: maps look like evidence. They imply the existence of the terrain they represent. (Though the practical traveler should note that Kircher put south at the top of his map. In fact many medieval cartographers put east at the top, because Jesus.)

Some books are published with maps; some books cast a spell so strong that they demand to be mapped after the fact. A hundred years after Dante published his Divine Comedy people were already drawing maps of the Inferno. The England of the Canterbury Tales and Pride and Prejudice and the Mississippi of Huckleberry Finn have all been mapped.

Fictional maps are a visual trace of the ridiculous, undignified passion that we pour into worlds that we know aren’t real. They seem to confirm the ridiculous faith we place in novels.

It didn’t matter that these places didn’t exist, what mattered was how much people wanted them to. Fictional maps are a visual trace of the ridiculous, undignified passion that we pour into worlds that we know aren’t real. They seem to confirm the ridiculous faith we place in novels—to see one is to say, silently and only to yourself, See? I knew it was real!

It’s hard to say for sure how fully aware Kircher was that his map of Atlantis was fictional, but it’s fair to say that Jonathan Swift knew that Lilliput and its implacable enemy Blefuscu didn’t exist when, sixty years later, he inserted a map of them into the first edition of Gulliver’s Travels. It’s a typical Swiftian joke: The novel in English had only just been invented, and fiction and nonfiction weren’t completely disentangled yet (there was significant debate only a few years earlier as to whether Robinson Crusoe really happened or not). Swift was offering a practical demonstration of how easily the tools of realism can be used to create something unreal.

Decorative antique nautical chart, collage with hand drawn illustration

Decorative antique nautical chart, collage with hand drawn illustration

But the modern fantasy map really came into its own with the work of J.R.R. Tolkien. Maps like the one of the Hundred Acre Wood in Winnie-the-Pooh were drawn to look like the work of a child, but Tolkien’s maps claimed the full authority of serious cartography. They were a testament to a new kind of worldbuilding, in which fictional settings aspired to the same kind of solidity and self-consistency that we were used to associating with reality. At first the maps were drawn by Christopher Tolkien, the author’s son, but for The Lord of the Rings Tolkien doubled down and hired a professional: Pauline Baynes, who before she was a celebrated illustrator was in fact a trained cartographer—she cut her teeth drawing naval charts for the Admiralty during World War II.

Not all fantasy novels are mappable. Novels are, after all, made of words, and therefore largely exempt from the strict observation of the laws of time and space in a way that maps aren’t. Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, for example, has no inherent geographical logic whatsoever. The knights just light out into the forest, questing or hunting, and the landscape stretches and distorts, or maybe shifts itself tectonically, to get them where the plot needs them, bang on time. The same is true of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. To be mapped is to be trapped and flattened, dried out and fixed on the page. Some books won’t put up with it.

Maps like the one of the Hundred Acre Wood in Winnie-the-Pooh were drawn to look like the work of a child, but Tolkien’s maps claimed the full authority of serious cartography.

But maps aren’t just window dressing, they’re fundamentally a part of fantasy as a genre. Before it’s about anything else, fantasy is about landscape: green fields, green hills, a place to which the characters and the reader feel connected in a way that’s no longer possible in our alienated postindustrial age. Fantasy is about longing, about the yearning to be not here but elsewhere. Maps are about the same thing. A map is not an idle exercise: It’s a plan to go somewhere.

Though it’s not always easy for fantasy novelists to live up to their maps. One reason George R. R. Martin took so long to deliver A Dance with Dragons was the difficulty he had calculating and reconciling all the distances and travel times—it was, he wrote on his blog, “a bitch and a half.” It was something Tolkien himself struggled with: ‘If you’re going to have a complicated story you must work to a map,’ he wrote, ‘otherwise you’ll never make a map of it afterwards.’

It’s a problem new to the cartographic age of fantasy: The map now actually precedes the territory. If you’ve ever wondered why the Beor Mountains in Alagaësia are ten miles high, it’s because when he was making the map Christopher Paolini accidentally drew them out of scale. He was going to fix it—but then he decided he liked them better that way.

__________________________________

Excerpted from “On Fantasy Maps” by Lev Grossman in Lost Transmissions: The Secret History of Science Fiction and Fantasy, edited by Desirina Boskovich. Copyright © Lev Grossman 2019. Reprinted with permission from Abrams.

Lev Grossman

Lev Grossman is the author of the New York Times bestselling Magicians trilogy. He has been Time magazine's book critic and lead technology writer for over a decade, and he has also written essays and criticism for the New York Times, Salon, Slate, the Wall Street Journal, Wired, the Village Voice and the Believer, among others. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and three children.