Why There Can Be No Freedom in Iran Without Freedom For Women

Fatemeh Jamalpour and Nilo Tabrizy on How the Murder of Mahsa Jîna Amini Sparked a Revolution

On September 16, 2022, a twenty-two-year-old Kurdish woman named Mahsa Jîna Amini was killed in Tehran by the city’s morality police. She was viciously beaten after having been detained by an officer who accused her of not dressing appropriately in public, in defiance of the country’s hijab rule, which broadly governs what women should wear. As this horrible incident was unraveling, details were quickly disseminated by a handful of local journalists on social media. Sajjad Khodakarami, an independent Iranian journalist based in Istanbul, broke the news of Jîna’s assault on Twitter, sharing that on September 13 she “was treated in Tehran’s Kasra Hospital due to severe injuries, including brain damage.”

On the same day, Hamed Shafiei, a reporter who covered political and local news for Shargh, one of the largest and most prominent Iranian newspapers, posted an Instagram story. He wrote, “I went to Kasra Hospital. The atmosphere was tense there, and people were shouting, ‘They killed someone’s daughter. The police killed her. The morality police killed her.’ ” The accompanying image of Jîna lying unconscious in a hospital bed, with a swollen face, tubes coming out of her mouth, and dried blood on her ears, went viral.

Word by word, story by story, we have survived our oppressors by force, with narrative as our lifeline.

As these threads of reporting began to come together, the regime tried to shut down coverage of the story. A police spokesperson told reporters at Shargh to disregard the incident with Jîna—that publishing what was happening at the hospital would only cause trouble for Shargh and for the police.

But the regime couldn’t stop what was already in motion. The news continued to be shared all over various platforms, both by media outlets and by individual reporters. And when Jîna succumbed to her injuries on September 16, the Shargh reporter Niloofar Hamedi defied orders to keep quiet and told the world about her death in a tweet. Alongside a photo of Jîna’s grandmother and father wrapped in a tight, tearful embrace outside the closed door of the ICU, Niloofar wrote that “the black dress of mourning has become our national flag.”

The Islamic Republic stood firm in its claim that Jîna had died due to a health issue, denying that the morality police had beaten her to death. But Iranians knew better, and the Friday after Jîna’s death swarms of people, mostly women, congregated in front of Kasra Hospital, overflowing with rage about seeing another one of our young women disposed of by the security state with such casual cruelty.

Poetry has seeped its way into our being; it’s part of our very Iranianness. And it isn’t only delicate or whimsical. It is now and has always been political.

Morality police vans, plainclothes officers of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and riot police surrounded the hospital to try to prevent people from mourning and demonstrating. Authorities started to violently arrest people, shooting at and beating them. Elaheh Khosravi was one of the first journalists on the scene. After the commotion made it impossible to stay at the hospital, she walked down Alvand Street to Argentina Square nearby. There, she witnessed and reported on an act of protest and mourning that became a symbol of the 2022 movement that followed Jîna’s death: a young woman, scissors in hand, cutting off her ponytail while shouting, “You [the regime] are forever dishonorable!” The image was reminiscent of “Daf,” a poem by Reza Baraheni, an Iranian poet:

A woman was running on the rigid beaches

Shouted: God, God, God, why have you forgotten Tehran’s sky?

For those of us in Iran who have lived through destruction, war, and turmoil, poetry and literature have always been our shelter. In some cultures, poetry is for the elite. Yet in Iran, it’s for the masses. Nearly every Iranian, regardless of economic status or educational level, knows the great Persian poets. Even those who cannot read can recite, from memory, a favorite verse written by Hafez or Rumi. Poetry has seeped its way into our being; it’s part of our very Iranianness. And it isn’t only delicate or whimsical. It is now and has always been political.

It’s fitting, then, that the legacy of Jîna’s death and the movement it would inspire would unfurl in real time through revolutionary songs and poetic slogans chanted at demonstrations and recorded in protest graffiti that covered the walls and streets that the authorities took from our people. For centuries, narrative expression has shaped how we bring life to the most urgent issues for our people.

One of the earliest poetic works that collectively shaped us is the Shahnameh, an epic poem by the Persian poet Ferdowsi. In AD 977, Ferdowsi began writing a story in more than fifty thousand rhyming couplets about the mythical tales of ancient Iran. He takes the reader on a journey from the creation of the world to the seventh century, when the Arabs conquered Iran and brought Islam to the Persian Empire. It took Ferdowsi more than forty-three years to complete this narrative, writing amid the Arab invasion that imposed a new language and religion on our people. Taking care to intentionally use Persian words, Ferdowsi preserved our language and history at a time when it could have been lost forever. Word by word, story by story, we have survived our oppressors by force, with narrative as our lifeline.

At the core of the slogans created and spread during the 2022 protests, the morphing of our ideas and desires into melodies and verse, is the simple human act of expression. We’ve been killed, imprisoned, and exiled when we dare ask for basic dignity. Expressing ourselves is how we resist repression; it’s how we’ve resisted since Shahnameh. In the days and weeks after Jîna’s death, Iranians logged on to Twitter by the thousands to explain why they were facing off against ruthless, violent authorities in the streets every day.

A then-twenty-five-year-old singer named Shervin Hajipour began gathering our hopes, stringing them together into a ballad called “Baraye,” meaning “For.” As the guitar comes in to form a sparse music bed, Shervin’s powerful and graceful voice echoes Iranians’ longings. Transformed into a vessel, he runs down the endless reasons that pushed people out of their homes and into the streets in daily protest:

For dancing in the streets

For our fear when kissing loved ones

For my sister, your sister, our sisters

For the changing of rotted minds.

Perhaps accidentally, or instinctually, Hajipour joined the centuries-long tradition of verse as political commentary that is a foundational pillar of our national identity. When he posted the song to his Instagram in the early days of the movement, it was viewed more than forty million times in less than two days. In Persian we have a phrase, “khak-e pay-e mardom,” which directly translates to “the dust beneath people’s feet.” It’s a phrase used to say, “I’m with the people.” Though the phrase has been co-opted by politicians like Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a pro-regime former president, to ridicule and disparage protesters, it has since been reclaimed. In writing and sharing this song, Hajipour was not only the dust beneath our feet, standing with us firmly and completely, but also our voice, our eyes, our hearts.

In Iranian culture, losing a child is considered the deepest grief, often referred to as “burning mourning.”

Two days after Hajipour shared “Baraye” online, he was summoned by the police and questioned for “encouragement to protest,” later released on bail in October 2022. He was barred from leaving Iran and lived life in limbo for two years while awaiting sentencing. In a video uploaded to Instagram on July 30, 2024, he finally informed his followers that he was ordered to turn himself in to begin serving a three-year-and-eight-month sentence for the lyrics in “Baraye.” Though his travel ban had by then been lifted, Hajipour said in the video that he would serve his sentence rather than leave Iran.

“For me it’s a question of how else was I supposed to protest? How else could I have critiqued what was going on?” he said, speaking directly to the camera, his voice lightly trembling. “Was there a more peaceful, civil way other than ‘Baraye’?”

Even the most beautiful, nonviolent means of expression are unsafe in Iran. Songs, reporting, and the strengthening of community under unlikely circumstances threaten the regime’s existence. For each Hajipour who is silenced, new words, verses, and slogans will rise, finding their ways into our bodies as we shout them into existence at a protest or write them online to live forever.

*

The evening after Jîna’s death, on assignment for the newspaper Ham-Mihan, my friend and colleague Elaheh Mohammadi drove eight hours overnight, through winding mountains and narrow roads, to Saqqez, Jîna’s hometown in Kurdistan. She arrived there at 6:30 a.m. and drove directly to the cemetery to cover Jîna’s funeral, not wanting to miss a moment of the service.

Half an hour later, men and women, young and old, began to stream into the Aichi cemetery wearing Kurdish outfits, waiting with crying eyes for Jîna’s body to arrive. Jîna’s parents, Mojgan Eftekhari and Amjad Amini, sat beside her empty grave. In Iranian culture, losing a child is considered the deepest grief, often referred to as “burning mourning.” Jîna’s mother filled her fists with dirt, cast them suddenly into the air over her head, and said, “Jîna, get up. Look, these people have come to see you. Our flower is gone.”

The funeral was the beginning of our revolution for a normal life, for justice and equality.

Close to the funeral start time at 10:00 a.m., people were still pouring in. The security officers tried to rush the family into burying Jîna before it got crowded. But her family refused and did not allow the officers to take Jîna’s body out of the ambulance. Jîna’s uncle announced in a short speech, “We will not bow down.” Her parents insisted that they had made an appointment with the people. And so, they waited. In the end, Jîna’s body was buried by the hands of thousands of people showing Kurdish solidarity.

The funeral was the beginning of our revolution for a normal life, for justice and equality. Elaheh called Elnaz, her twin sister, and shouted, “Elnaz, a revolution has started here! I will stay longer.”

On Jîna’s tombstone, her father wrote, “Dear Jîna, you will not die. Your name will become a symbol,” foreshadowing the important role her death would play in the movement. Her grandfather read the poem Tehran by the Kurdish poet Sherko Bekas, the popular contemporary Kurd poet, whose poems many of the millions of Kurdish people in Iraq, Iran, and Syria can recite by heart. The subject matter Bekas deals with is always life, love, and freedom:

Tehran imposed a mandatory hijab on the trees

Tehran sewed a robe on the water’s body Tehran put a turban on the garden

Tehran forced singing to have a beard

Tehran made music a widow

And it made a funeral from life

Tehran does not laugh at anyone

Except for death

Tehran does not like anything other than death

The names of all women, girls, and boys in Tehran is death

And life is never born from a mother in Tehran.

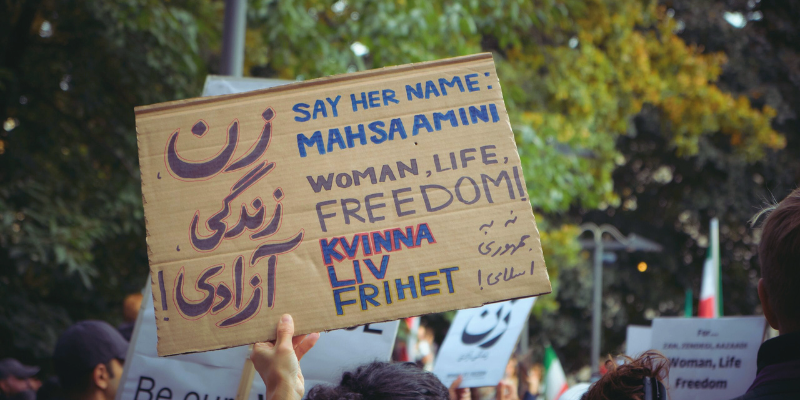

The guests at Jîna’s funeral chanted, “Jin, Jîyan, Azadî,” or “Woman, Life, Freedom,” during the service, a slogan that derived from the political writings of an imprisoned Kurdish leader named Abdullah Öcalan. Colloquially called Apo, which means “uncle” in Kurdish, Öcalan was the son of a poor farmer in Turkey. Like those of many revolutionary leaders, his theories originate from personal life experiences. Öcalan’s life was forever changed after seeing his sister Hawa forced into a child marriage in exchange for money and wheat.

In 2010, in an article called “The Revolution Is Woman,” he wrote that calling for freedom without gender equality is futile and illusory. Öcalan presented his ideology on three axes: women’s freedom, ecology and attention to the environment, and radical democracy, which together came to form the foundation of what we now know as “Woman, Life, Freedom.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from For the Sun After Long Nights by Fatemeh Jamalpour and Nilo Tabrizy. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Fatemeh Jamalpour and Nilo Tabrizy

Fatemeh Jamalpour and Nilo Tabrizy

FATEMEH JAMALPOUR is a feminist freelance journalist banned from working in Iran by the Ministry of Intelligence. She has contributed to The Sunday Times, The Paris Review, and the Los Angeles Times and previously worked with BBC World News in London and Shargh newspaper in Tehran. Fatemeh was a 2024–25 Knight-Wallace Fellow at the University of Michigan. NILO TABRIZY is an investigative reporter at The Washington Post. She works for the Visual Forensics team, where she covers Iran using open-source methods. Previously, she was a video journalist at The New York Times, covering Iran, race and policing, abortion access, and more. She is an Emmy nominee and the 2022 winner of the Front Page Award for Online Investigative Reporting. Nilo received her M.S. in Journalism from Columbia University and her B.A. in Political Science and French from the University of British Columbia.