Why The Turn of the Screw Haunts Us 125 Years Later

“That queasy opacity is at the heart of the novella’s power... The reader is never sure what, exactly, is happening.”

This year marks the 125th anniversary of one of the most influential ghost stories ever written. The Turn of the Screw by Henry James is a novella of shadows, lurking dread and psychological menace. The story is deceptively simple: a vulnerable, highly sensitive young woman takes the position of governess at Bly, a remote manor house. The children she is employed to care for, Miles and Flora, are delightful, and at first Bly seems to be a place of sun-dappled sanctuary. That idyll is soon shattered.

The (unnamed) governess’s pleasure in the role swiftly turns to terror when she becomes convinced that the manor, and particularly the children, are haunted by the ghosts of former servants Peter Quint and their previous governess, Miss Jessel. The spirits—visible only to the governess narrator—have something of the damned about them. It is implied, but never made explicit, that they corrupted the children in some unspeakable, possibly sexual, way.

But is the governess a reliable narrator? Is she even sane? Is it possible that these ghostly fiends are an outward manifestation of her own repression and thwarted desire?

James’s leisurely, labyrinthine prose never quite takes us to an answer to those very modern questions

This Victorian ghost story was written the year after Sigmund Freud began to analyze himself—a process that led to the birth of modern psychoanalysis. It’s tempting to speculate that in 1898 James made some liminal connection with the zeitgeist. One reading of The Turn of the Screw could suggest that the governess—whose life to date has been that of a sheltered vicar’s daughter—is not battling external demons, but instead is transferring deeply buried, but deeply shocking, desires to the environment around her.

It is clear from the outset—where she is interviewed in Harley Street for the position at Bly by an attractive young gentleman— that she is imaginative and romantic. While her prospective employer emphasizes that he wants nothing to do with the lives and affairs of his orphaned nephew and niece (even going as far as forbidding her to contact him), the governess allows herself to dwell upon times when he might visit Bly and ‘admire’ her guardianship.

Once marooned in the country with only an older housekeeper, a few servants and two children for company, her imagination— possibly—goes into overdrive.

Her fears are both erotic and neurotic.

In an age where mental health is a priority, we can—perhaps—sense that the febrile governess is acutely susceptible and troubled.

In the Victorian era ‘hysteria’ (what a horrible word that is) was a common diagnosis for women. Almost any female ailment could be made to fit the accepted indicators of hysteria because there was no set list of symptoms.

James was sadly familiar with this. His much-loved sister Alice suffered lifelong mental and physical health problems that were generally dismissed as ‘hysteria’ in the style of the day. She died in 1892 and it is again all too easy to speculate that the writer, an acute observer of humanity, drew upon her distressing experience.

But there is more to analyze, taking us into deeper Freudian territory. The young governess’s relationship with her charge, master Miles, is perhaps the most unsettling aspect of a tale where dark desires and unnamed terrors flicker just off the page. There is a hint – and the implication from which readers have inferred so much is no more than the kiss of a cobweb – that her feelings for the boy go deeper than that of carer or guardian. At the climax of the story, the governess actually suffocates Miles with what she believes is soul-saving love.

Is that love misplaced? Is it possible that her shame causes her to murder the object of her buried sinfulness?

Henry James never answers these questions and that queasy opacity is at the heart of the novella’s power. The most intriguing and eternally fascinating aspect of The Turn of the Screw is that the reader is never sure what, exactly, is happening.

Ten-year-old Miles and eight-year-old Flora are apparently ‘radiantly’ perfect. Too perfect? Are they sweetly poised and self-possessed, or are they actually possessed? Are those dead, disgraced former servants Peter Quint and his lover Miss Jessel using them as vessels through which to channel and continue their hideous depravity?

The governess comes to suspect that the children’s charm and—in the case of Miles particularly—distinctly adult courtesy masks something corrupt and diabolical. And through her account, the reader begins to share that dread.

I think it may be fair to say that right here Henry James created the trope of the ‘creepy’ child. Now a classic staple of the horror genre, it’s hard to think of any instances that pre-date The Turn of the Screw. It’s important to stress how important and bold this was. The high Victorian version of childhood was saccharine and sacred; a time of innocence and purity, but James subtly subverts that shibboleth and asks the reader to imagine a very different possibility.

The title of the book is a masterful nod to this brave creation—the real ‘turn of the screw’ is that there is not one, but two of the little monsters!

Or are there?

You may have noticed that I’ve threaded this appreciation with questions and caveats. If you ignore the psychological complexities of The Turn of the Screw you are still reading a strange and deeply unsettling ghost story—a tale of good versus evil. Many readers are certain that is how it should be viewed and who is to say they are wrong? Reading is subjective.

This conundrum has created an after-life for the tale that is currently more fashionable than the hefty language in which it was written. (As Mark Twain, a contemporary of Henry James, rather brutally observed; “Once you put one of his books down, you simply can’t pick it up again.”)

However, despite writing novels that can appear to the modern reader as the literary equivalent of a Victorian over-stuffed sofa, James remains a master story-teller and the multiple ambiguities of The Turn of the Screw continue to inspire writers and film-makers.

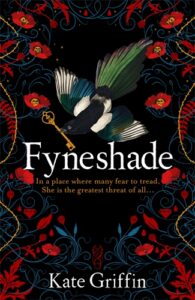

My new novel, Fyneshade, owes a great debt to Henry James and also to Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre. The glory of ‘governess gothic’—as I like to think of it—is that it allows the central character to occupy a space that is a crossing point. Neither upper class, not quite servant class, the governess is an outsider and observer. My own ‘turn of the screw’ to the genre is the fact that Marta, my beautiful young governess, is the most terrifying thing in the house.

Given that James was a failure as a playwright, it is ironic that generations of screen-writers have been haunted by The Turn of the Screw. But film is a place where the interior lives of characters are, quite literally, ‘lit large’. Henry James’s writing transfers perfectly to the screen where the flick of an eye, the tremor of a lip or the brush of a fingertip is worth three pages of script.

In terms of adaptations, most recently The Haunting of Bly Manor was a Netflix success, but there are countless other versions and riffs on the story, including The Others (2001) and even Michael Winner’s unlikely The Nightcomers (1971) starring Marlon Brando as Peter Quint!

Best in show is The Innocents (1961) which was directed by Jack Clayton and partly scripted by Truman Capote and John Mortimer. Filmed in shimmering, otherworldly black and white, it takes James’s dense prose and creates a thing of deadly and terrifying beauty.

And that really is the point. However you read it, the Turn of the Screw is not a polite, 125-year-old Victorian ghost story—it is a tale of savage, timeless horror.

When Henry James himself re-read it, he was frightened to go bed!

_______________________

Kate Griffin’s Fyneshade is available now from Serpent’s Tail.

Kate Griffin

Kate Griffin was born within the sound of Bow bells, making her a true-born cockney. She has worked as an assistant to an antiques dealer, a journalist for local newspapers and now works for The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. Kitty Peck and the Music Hall Murders, Kate's first book, won the Stylist/Faber crime writing competition. Kate lives in St Albans. Her new book, Fyneshade, is now available.