Why the Bible is the Literary Book of Books

David Keenan on the Necronomicon, Danilo Kiš' Encyclopedia of the Dead, and books that contain all other books

As a kid I was very religious, but it was more out of fear of the Devil, if I’m being honest (and the Devil’s big scaly pecker, which a thug name of Scott “Skidmark” McCormack drew on the front of my jotter at Sunday School one day, which meant I had to cover the jotter with wallpaper before I got home and my mum saw it), than any genuine love of Christ.

I loved the Bible from an early age, thanks to my mum’s punishing belief that sending me to Sunday school and Bible class every single week of my childhood might instill some kind of faith in me and make for a happier life, which it certainly did, although my faith, ultimately, is non-denominational; my faith requires no belief and adheres to no tenets beyond the perfection of suffering, joy, and all of creation.

Biblical cadence is in my blood. I grew up reading aloud from the Bible and I love its rhythms, its word orders, its promise of revelation through the power of the Word. Unlike the modernists, or should I say, unlike what I was told the modernists were up to at university, I have never lost faith in the power of the Word to point to the thing itself.

Things aren’t words, sure, but a great writer, like “St John” or Clarice Lispector or Danilo Kiš, can use words to point to what they are not, to deliver the thing-in-itself, beyond the mere “describing” of it, in a way that can make you gasp. But I love the Bible the most because my old minister at Clarkston Parish Church called it The Book of Books.

Wow, I thought, when he first called it that, a book that contains books, that contains books, what a thought. It made the Bible seem alive to me, like an entity or an organism, and I began to imagine the Bible reading itself; I imagined this fantastic feedback loop where the reading of a book by a book gifted that book eternal life. Plus, the minister kept all sorts of things pressed between the pages of his Bible—a cool Bible bound in black leather—things like pressed flowers and photographs and a Buddhist mandala and a purple Quality Street wrapper and receipts for gifts, and it only added to the sense of a book being a living thing that you could interact with in all sorts of ways.

As I grew up my reading tastes began to change. Hand-in-hand with my extreme religiosity (which meant that I was the only boy at my school who refused to swear, even when thugs like Skidmark tried to force me) I liked classic boys’ novels like The Hardy Boys and Biggles.

But then I discovered the science fiction comic 2000 AD as well as Terrance Dicks’ novelizations of Doctor Who episodes and the books of J. R. R. Tolkien and my tastes flipped, almost completely, to science fiction, fantasy and horror. That’s when I first heard of the dreaded Necronomicon, aka. The Book of the Dead.

I began to imagine the Bible reading itself; I imagined this fantastic feedback loop where the reading of a book by a book gifted that book eternal life

My friend Dennis, a sci-fi nut, told me about it. It’s a grimoire, he told me, it’s like an encyclopedia of spells and demons written by a mad Arab. Uh-oh.

Dennis loaned me a three-volume paperback set of the collected stories of H. P. Lovecraft, the “creator” of the Necronomicon, which I hid under my bed. Before I even dared open a page I had to find out if, indeed, the Devil was actually real. I finally confronted my mum.

I need to ask you something, I said to her, and it is really important that you tell me the honest truth here. Tell me, I said, does the Devil exist?

No, my mum said. The Devil does not exist.

So, there is only God? I asked her.

There is only God.

It was the happiest moment of my life. There is only God. In the books within books of H. P. Lovecraft, there is only God, I told myself as I read about this Necronomicon, this Encyclopedia of the Dead. In “The Dunwich Horror,” Wilbur Whateley visits the Miskatonic University’s Library to consult an unabridged copy of the Necronomicon, written by the “mad Arab” Abdul Alhazred, a series of “howlings” of the names of the “Old Ones”—mad, evocative, Biblical names like Cthulhu and Yog-Sothoth—with talk of trans-dimensional gates and of incantations that would raise entities from the chthonic depths.

Within that book, is a book that contains all books—an entity, a living being, a feedback loop of forever.

My mind was completely blown. I wanted to secret a book within a book, I wanted to cast spells and send them out there, I wanted to create books that were alive with these occult howlings and where there is only God, and all of his names, forever.

When I was twenty, I came across another book that has stayed with me ever since. It was The Encyclopedia of the Dead by the Yugoslavian author Danilo Kiš. Of course I pounced on it as soon as I read the title on the spine. A grimoire! A Necronomicon! A book of books! In The Encyclopedia of the Dead the narrator is locked into a library that contains The Encyclopedia of the Dead, an on-going work dedicated to recording every single detail of the lives of everyone who has ever lived, with the stipulation that no one is included who is included in any other encyclopedia.

In other words, it is an encyclopedia of all the forgotten dead for use at the resurrection, so that souls may not forget everything that happened to them, as well as a book that realizes—and manifests—the unique value of every single unrepeatable moment forever, made up of “the sum total of everyday occurrences of ordinary folk.” Because there is only God.

The narrator looks up their father, and relives his life in every detail. Between the pages of their father’s entry there is the schematic of a flower that their father had painted across the walls and objects of their home near the end of his life, which turns out to be the same shape as the cancerous bloom that killed him.

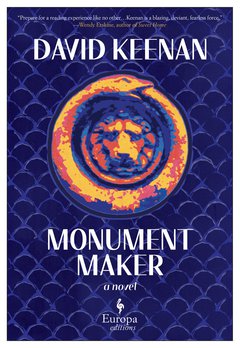

I wrote my new book, Monument Maker, over the space of ten years. It is my own Encyclopedia of the Dead, my own Book of Books. In it, I bring back to life members of my own family, by rescuing them from the silence of the past. I also included a magical book of my own in there, a grimoire that was dictated to me straight out of the air titled “Belly of the Fish of Christ, Ship” which the characters discover and base an initiatory cult around.

And within that book, is a book that contains all books—an entity, a living being, a feedback loop of forever—inspired by Daniel, and St John, and H. P. Lovecraft, and Danilo Kiš.

______________________________

Monument Maker by David Keenan is available via Europa Editions.

David Keenan

David Keenan is the author of many critically-acclaimed novels, including the cult classic This is Memorial Device, which won the London Magazine Prize; For the Good Times, which won the Gordon Burn Prize; The Towers The Fields The Transmitters, Xstabeth and Monument Maker, which was a Rough Trade Book of the Year. He lives in Glasgow, Scotland.