Why Strikes Matter

Erik Loomis on the History (and Future) of Class Struggle in America

The workplace is a site where people struggle for power. Under a capitalist economy such as that of the United States, employers profit by working their employees as hard as they can for as many hours as possible and for as little pay as they can get away with. Their goal is to exploit us. Our lives reflect that reality. Many of us don’t enjoy our work. We don’t get paid enough. We have to work two or three jobs to make ends meet if we have a job at all. Our bosses treat us like garbage and we don’t feel like there is anything we can do about it. We face the threat that machines will replace us. Our jobs have moved overseas, where employers can generate even higher profits. Sometimes a job at Walmart is the only option we have.

In our exploitation, we share common experiences with hundreds of millions of Americans, past and present. Our ancestors resisted. So do we, sometimes by forming a union, sometimes by taking a couple extra minutes on our break or by checking social media on the job. All of these activities take back our time and our dignity from our employer. Class struggle—framed through transformations in capitalism, through other struggles for racial and gendered justice, and through changes in American politics and society—has played a central role in American history. Future historians will see this in our lives as well.

This book places the struggle for worker justice at the heart of American history. This is necessary because we don’t teach class conflict in our public schools. Textbooks have little material about workers. As colleges and universities have devalued the study of the past in favor of emphasizing majors in business and engineering, fewer students take any history courses, including in labor history. Labor unions and stories of work are a footnote at best in most of our public discussions about American history. Most history documentaries on television focus on wars, politicians, and famous leaders, not workers. Labor Day was created as a conservative holiday so that American workers would not celebrate the radical international workers’ holiday May Day. Yet today, we do not remember our workers on Labor Day like we remember our veterans on Veterans Day. Instead, Labor Day just serves as the end of summer, a last weekend of vacation before the fall begins. That erasure of workers from our collective sense of ourselves as Americans is a political act. Americans’ shared memory—shaped by teachers, textbook writers, the media, public monuments, and the stories about the past we tell in our own families, churches, and workplaces—too often erases or downplays critical stories of workplace struggle.

“In our exploitation, we share common experiences with hundreds of millions of Americans, past and present. Our ancestors resisted. So do we, sometimes by forming a union, sometimes by taking a couple extra minutes on our break or by checking social media on the job. All of these activities take back our time and our dignity from our employer.”

Instead, our shared history tells myths about our economy meant to undermine class conflict. We are told that we are all middle class, that class conflict is something only scary socialists talk about and has no relevance to the United States today. Our culture deifies the rich and blames the poor for their own suffering. “Why don’t they pull themselves up by their bootstraps?” so many people say. This ignores the fact that millions of Americans never had boots to pull up. Most of us are not wealthy and never will be wealthy. We are workers, laboring for a few rich and powerful people, mostly white men who are the sons and grandsons of other rich white men. We have a hierarchical society that has used propaganda to get Americans to believe everyone is equal. We are not equal. The law routinely favors the rich, the white, and the male.

During the 20th century, workers fought and died to solve some of these problems, even though white men still benefited more than women or people of color. Workers formed unions, joined them by the millions, and convinced the government to pressure companies to negotiate with them. Unfortunately, the period of union success ended in the 1970s. So did the rising tide for American workers that created the middle class. With the decimation of unions, the fall of the middle class and the evisceration of the working class have followed. Politicians talk about the middle class during elections, but they too often pursue policies that increase inequality and give power to the rich. This has transformed the fundamentals of the American Dream. The idea of getting a job and staying with it your whole life, working hard to feed your family and educate your children, and then retiring with dignity is gone. Now, we are expected to take on massive student debt, enter an uncertain job market, and change jobs every few years, all the while being told by our parents and the media that we should stop eating avocado toast and instead buy a house, as if a $7 appetizer and not $50,000 in student loan debt is why young people suffer financial instability. Pensions are dead, and the idea of retiring seems impossible even for many baby boomers, who have significant consumer debt and shaky finances as they reach their later years.

We cannot fight against pro-capitalist mythology in American society if we do not know our shared history of class struggle. This book reconsiders American history from the perspective of class struggle not by erasing the other critical parts of our history—the politics, the social change, and the struggles around race and gender—but rather by demonstrating how the history of worker uprisings shines a light on these other issues. Some of these strikes fought for justice for all. Sometimes they made America a better place and gave us things we may take for granted today, such as the weekend and the minimum wage. But we also should not romanticize strikes. Some workers went on strike to keep workplaces all white. Sometimes strikes backfire and hurt workers in the end. Working Americans do not always agree with each other. Race, gender, religion, region, ethnicity, and many other identities divide us. Just because a Mexican immigrant and a fourth-generation Italian American work in the same place does not mean that they like each other or see eye-to-eye on any issue, including their own union, if they have one.

“Our shared history tells myths about our economy meant to undermine class conflict. We are told that we are all middle class, that class conflict is something only scary socialists talk about and has no relevance to the United States today. Our culture deifies the rich and blames the poor for their own suffering.”

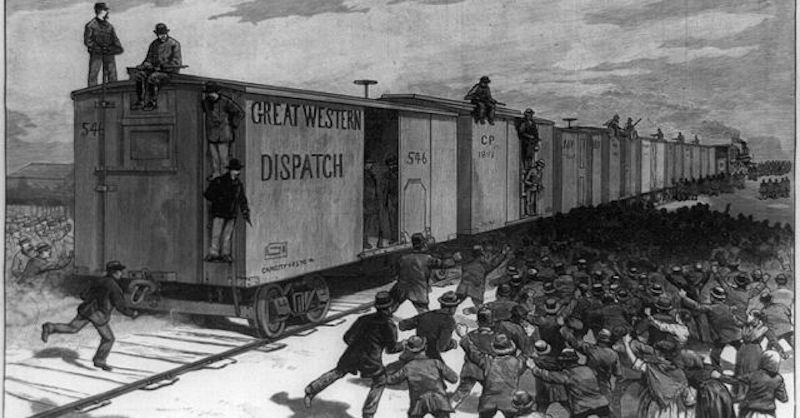

Taking a hard look at the history of strikes helps us in the present. This book argues for two interlocking necessities for workers to succeed in the past, present, and future. First, workers have to organize collectively to fight employers. Through American history, workers have fought to make their jobs better paid, fought for the right to negotiate a contract with their employer, fought to feed their children or have the chance to send them to college, fought for a completely new society that valued work as it deserved. Like the Chicago Teachers Union in 2012, workers of the past two hundred years also had to strike to win their struggles. Strikes take place when workers collectively decide to stop working in order to win their goals. Usually that happens with a labor union, which is an organization that workers create to represent them collectively. In the United States, this has usually meant the strikers have the aim of the union winning a written contract from the employer that lays out the rules of work and gives workers set wages, working hours, and benefits. But strikes happen with or without unions. They can be spontaneous acts by workers—paid or unpaid, with their union’s support or without it—when they throw down their tools or their washrags or their chalk and they walk off the job for whatever reason they want.

Strikes are special moments. They shut down production, whether of manufacturing cars or manufacturing educated citizens. The strike, the withholding of our labor from our bosses, is the greatest power we have as workers. As unions have weakened in recent decades, we have far fewer strikes today than we did 40 years ago. During the 1970s, there were an average of 289 major strikes per year in the United States. By the 1990s, that fell to 35 per year. In 2003, there were only 13 major strikes. When a strike like the CTU action takes place, it forces people who claim to support the working class to announce which side they are on. Do they really believe in workers’ rights or will they side with employers if a subway strike blocks their commute to work or a teachers’ strike forces them to find something to do with their children for the day? Strikes are moments of tremendous power precisely because they raise the stakes, bringing private moments of poverty and workplace indignity into the public spotlight. And unless you are a millionaire boss, we are all workers with a tremendous amount in common with other workers, if we only realize that all of us—farmworkers and teachers, insurance agents and construction workers, graduate students and union staffers—face bad bosses, financial instability, and the desperate need for dignity and respect on the job.

We might like to believe that if all workers got together and acted for our rights, we could win whatever we want. In theory, if every worker walked off the job, that might happen. Unfortunately, real life does not work that way. Given that we are divided by race, gender, religion, country of origin, sexuality, and many other factors, class identity will never become a universal sign of solidarity. Employers know this and act to divide us upon these bases. For most of American history, the government has served the interests of wealthy employers over those of everyday workers like you and me, sometimes even using the military against us. At the local, state, and national levels, employers have far greater power than workers to implement their agenda, especially unorganized workers who lack a union. Therefore, in addition to worker action, organizers and union leaders have discovered a second requirement for success: Workers have to neutralize the government-employer alliance. After decades of struggle, in the 1930s, a new era of government passed labor legislation that gave workers the right to organize, the minimum wage, and other pillars of dignified work for the first time. While employers’ power never waned in the halls of government, the growing power of unions neutralized the worst corporate attacks until the 1980s. Since then, the decline of unions and a revived, aggressive lobby attempting to drive unions to their death have rolled back many of our gains. Once again we live in a country where the government conspires with employers to make our work lives increasingly miserable. Unions are the only institution in American history to give working people a voice in political life. This is precisely why corporations and conservative politicians want to eliminate them.

There is simply no evidence from American history that unions can succeed if the government and employers combine to crush them. All the other factors are secondary: the structure of a union, how democratic it is, how radical its leaders or the rank-and-file are, their tactics. The potent and often interlocking strategies of the state and bosses build a tremendous amount of power against workers. That was true in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and it is true under the Trump administration. Workers were and are denied basic rights to organize, income inequality is rampant, and the future of unions seems hopeless. Workers and their unions have to be as involved in politics as they are in organizing if they are to create conditions by which they can win. To stop involvement with the two-party political system would be tantamount to suicide. Having friends in government, or at least not having enemies there, makes all the difference in the history of American workers.

“Strikes are special moments. They shut down production, whether of manufacturing cars or manufacturing educated citizens. The strike, the withholding of our labor from our bosses, is the greatest power we have as workers.”

In Donald Trump, we face the most racist and misogynistic president in a century, a fascist Islamophobe who has demonstrated his utter contempt for the Constitution and the values that have made the United States the best it can be, even if it was never great for many of its citizens. Trump won in 2016 in part because he tapped into white Americans’ anxiety about their unstable economic futures. Video footage from Carrier’s announcement that it would close its Indiana heating and air-conditioning manufacturing plant to move its production to Mexico touched home for millions of Americans who do not see a path to a better future. For them, the American Dream is dead. Of course, African American, Asian American, Native American, Middle Eastern, and Latino workers also share those economic anxieties. But as has happened so often throughout American history, Trump managed to divide workers by race, empowering white people to blame workers of color for their problems instead of pointing a finger at who is really responsible for our economic problems: capitalists.

Capitalism is an economic system developed to create private profits. Within that broader definition, there are many forms of capitalism, some with socialist tendencies to ensure that the benefits of the economy are distributed relatively equally throughout all of society. In the modern United States, business and the government have dedicated themselves to a more fundamentalist version that uses the state to promote profit and keep workers subjugated under employer control. That has led to the income inequality that defines modern society. Whether some form of capitalism can work for everybody is a question people have debated for nearly two centuries. Some radicals reject capitalism entirely as a system that will never treat workers fairly. Others believe the state, businesses, and unions can all work together to create a form of capitalism where everyone benefits. We should be debating what the future of American and global capitalism looks like, or whether we should replace it entirely. I argue that at the very least we can use the government to create equitable laws and regulations to ensure that everyone lives a dignified life under a broadly capitalist economy. But that can only happen when workers reject the fundamentalist capitalist propaganda, such as from Ayn Rand and Fox News, and instead stand up for the rights not only of themselves, but of their friends, families, and co-workers. Solidarity is the answer for the future, which means sacrificing for others as they sacrifice for you. The extent that we will stand up for the rights of others, including at the workplace, will determine whether we will continue to see growing inequality and political instability in our world or we will see the world get better in our lifetimes.

__________________________________

From A History Of America In Ten Strikes. Courtesy of The New Press. Copyright © 2018 by Erik Loomis.

Erik Loomis

Erik Loomis is an associate professor of history at the University of Rhode Island. He blogs at Lawyers, Guns, and Money on labor and environmental issues past and present. His work has also appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, Dissent, and the New Republic. The author of Out of Sight (The New Press) and Empire of Timber, he lives in Providence, Rhode Island. His latest book, A History of America in Ten Strikes is available now from The New Press.