Why Should We Care About Penguins?

Naira de Gracia Explores the Importance of Species Conservation in Antarctica

I braced against the wind in the middle of a chinstrap penguin colony blanketing a rocky ridge. All around me penguins waddled through the colony or sat incubating their eggs on nests built from pebbles. The birds squabbled and crooned to one another. Some were in ecstatic display, flippers flung out from their bodies, heads pointing straight up, chests rising and falling in time with their screeching calls. The sound came from all directions and the noise was deafening. Penguin colonies are an assault on the senses: a cacophony of calls, a pungent fishy odor, and the penguins’ short black-and-white bodies always in movement.

It was time for the annual nest census, which I was conducting with my coworker Matt. We tiptoed through the fray, laying bright ropes down between the nests to section them into countable pieces. Sitting on eggs, the penguins reached over to investigate the rope with their bills, tugging it and shaking it.

By the time we finished, the ropes were brown and muddy with the thick penguin muck ubiquitous across all the colonies. We tried to discern the ropes’ shape from uncontaminated patches of color and count the nests on a rusty tally-whacker, a metal yo-yo-size counter that kept track of the numbers every time my finger pressed a rusty button.

A passing penguin mounted my boot and directed a flurry of flipper slaps at my calf, squawking its displeasure with characteristic chinstrap belligerence. If I’d looked down to nudge him off, I would have lost my concentration and had to count the section of nests again, so I let him go ahead and slap me. The sting kick-started my blood flow and pumped warmth to my increasingly numb feet.

The decrease in sea ice is causing cascading changes across the antarctic ecosystem—some of which we are only just beginning to discover.

It was a rare sunny day, early in my first season as a technician for a National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) ecosystem-monitoring field camp, and the snow-covered ground blazed with light. From my position at the top of the ridge, the small peninsula of Cape Shirreff was laid out before me, all rolling hills and ragged coastline. Since October, when I’d arrived, the snow on the hilltops had melted, exposing a dark earth where moss grew in small rusty patches and gray-green lichen awakened from a long winter dormancy.

On the rocky beaches antarctic fur seals huffed and howled into the wind, in the full throes of their breeding season. I could see their shapes down below: the hulking bulls lording over their harems, the sleek females scattered on the rocks with squirmy pups tucked up against them. To the south was the Anguita Glacier, a great wall of ice, covering the land that connected the peninsula to the rest of the island. All other edges of the Cape bordered the sprawling expanse of the Southern Ocean.

The small thumb of land that was Cape Shirreff jutted out from Livingston Island, Antarctica. It was a mile and a half long, half as wide, and had been the entirety of my world for two months. Matt and I, along with three other field-workers, were living and working at the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, just above the antarctic circle. South America, the nearest nonpolar continent, was about six hundred miles away.

The nearest US base in Antarctica was some two hundred miles away. We had been dropped off by a ship two months ago, with all our gear and food, and would be picked up in three more. Our crew of five was the only human presence on this isolated promontory.

Our home was a one-room plywood hut that served as a living room, kitchen, office, and bedroom. We had no internet, no running water, limited electricity. We worked every single day, in all weather: snow, wind, rain, blizzards, gales, hail, sun. Christmas, New Year’s, Halloween, weekends, full moon, new moon. We measured and counted, captured and released, tracked and took notes. My job, in essence, was to observe.

Our planet’s southern ecosystem is changing, and there are few witnesses. The Western Antarctic Peninsula is undergoing the most dramatic regional changes in Antarctica, with one of the fastest warming rates in the world. Since 1950, average winter temperatures have increased by 7˚C (five times the global average). The onset of sea ice in late autumn comes later year by year, decreasing the number of annual days of ice and the amount of ice overall.

In Antarctica, every life-form is attuned to the yearly cycle of ice. For antarctic krill, the species on which this whole ecosystem depends, ice is a nursery. The decrease in sea ice is causing cascading changes across the antarctic ecosystem—some of which we are only just beginning to discover.

It is the curse of a biologist to justify the existence of their study species to the world.

Long-term monitoring projects such as the one at Cape Shirreff allow us to see these changes play out among Antarctica’s top predators. Seals and penguins are indicator species: changes in their reproductive success and population can tell us what is happening with their food source. The information we gather at the Cape is ultimately brought before CCAMLR, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, the international body that sets limits to the global krill-fishing industry. NOAA administered the monitoring program on a national level as it fell under its oceanic purview.

Every figure about antarctic marine species is the result of an enormous output of time and labor. For every single dot on a graph scientists present to clean-cut diplomats and policy makers, there is a grimy field-worker like me, stationed on an isolated island, surrounded by penguins, covered in penguin muck and smelling like fermented shrimp, writing down metrics and surveys in an equally grimy field notebook.

For every long-term population trend reported in a journal article there are decades of field biologists standing in wind and snow, monitoring penguins or seals, hitting tally-whackers with numb fingers, far from family and friends and anything resembling human civilization. Our lives are tied to the weather, the season, and the wildlife itself.

It’s not glamorous work. You’re dropped on this frigid island with four other people and no privacy. Your body is buffeted by the elements, your mind strains under the work’s demands, your heart is rubbed raw with beauty. You live among wild things in a wild place, stand on a stark island facing your own stark nature. There are no shops, no roads, no TVs, no trails, no distractions from the machinations of your own mind. Just a handful of lonely shelters, your crew, the wind, the rocks, and the penguins.

Yet, it is a joy to work at Cape Shirreff, for reasons that, to field biologists, seem self-evident. But personal fulfillment does not fund research. It is the curse of a biologist to justify the existence of their study species to the world. Beneath the grant proposals, paper introductions, and presentations must lie proof that the species under scientific scrutiny have immediate value to our society.

This is particularly complicated for ecosystems that remain far from human experience. Only recently have humans populated the barren shores of this continent, and even then, ever so sparsely. What of ecosystems so remote that few will ever encounter them? In the two five-month field seasons I was there, I kept trying to articulate to myself the value of other species to human lives, beyond their scientific role as indicators for the wider ecosystem’s health. Why should we work so hard to maintain biodiversity in a place so remote? Why, exactly, should we care about penguins?

__________________________________

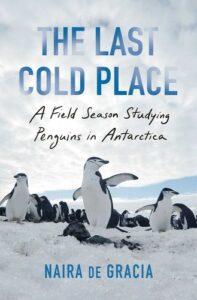

Excerpted from The Last Cold Place: A Field Season Studying Penguins in Antarctica by Naira de Gracia. Copyright © 2023. Reprinted with permission of Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Naira de Gracia

Naira de Gracia grew up moving around the world with her journalist parents and sibling. She graduated high school in Cairo, Egypt, and attended college in California. After completing her BA in biology, she worked as a wildlife technician for six years, on remote islands in the Hawaiian chain, the Antarctic, the Samoan archipelago, the Bering Sea and off the coast of California, continuously writing about her experiences. She currently lives in Wellington, New Zealand. The Last Cold Place is her first book.