Why Sara Gran Self-Published After Years in the Book Industry

In Conversation with Christopher Hermelin on So Many Damn Books

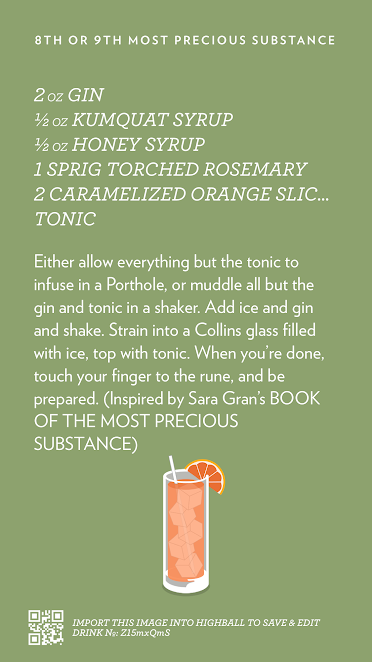

Sara Gran joins Christopher in the Damn Library to talk The Book of the Most Precious Substance, which is wildly exciting—her books are some of the most cited in So Many Damn Books history. They get into plants, and spells, and the lure of rare book buying. Plus, Sara goes into what made her decide to self publish this book after so many years in the industry. And then she brings Generation Lost by Elizabeth Hand to discuss, a novel about not having a camera at the right time, amongst other things. Get into it!

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts!

What’d you buy?

Christopher: Either/Or by Elif Batuman, The Every by Dave Eggers

Sara Gran: African Violets

*

Also mentioned:

Come Closer by Sara Gran • Generation Loss by Elizabeth Hand • The Infinite Blacktop by Sara Gran • Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore by Robin Sloan • The Ninth Gate (film, dir. Roman Polanski) • Works of Charles Portis • The Trickster and the Paranormal by George P Hansen • Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle • Raymond Chandler’s Phillip Marlowe novels • The Book of Lamps and Banners by Elizabeth Hand

*

Recommendations:

Sara Gran: Let your house get dirty, work on your projects instead

Christopher: The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon, read by David Colacci

*

From the episode:

Christopher: As many books are in this book, there’s also quite a bit of sex. There’s more than in any other book that you’ve written. And I’m curious if that has anything to do with how it ended up being published. Because this is your first book on your own imprint.

Sara: It was part of it. Because I felt like it had a lot of sales potential, probably more than my other books. And it may or may not sell well, you just never know until you know. But I felt like it had more commercial potential than my other books had had. And I also felt like handing a book with this really, really tricky sexual material into it with a big mainstream New York publisher was just going to be a shit show. I just knew it would be a shit show one way or the other. There would be some form of picking on what I had done. Either it would be, “Put more sex into it and make it straightforward erotica,” or it would be, “This is too much sex and the sex is too weird, and it involves things that some people don’t believe exists, and we can’t have that either.”

I felt like this is a book that would not be helped by the editorial process, although often I desperately need help from an editor. And I don’t mean to discount that role. But for this book in particular and me being 50 and having done this for 25 years now, I felt like I was just better off writing exactly what I wanted to write, with all of that sex, with all of the other sort of occult stuff in it, all of the stuff that someone in a New York publishing house might not quite grasp, and just get it out there.

Christopher: So then, tell me about starting Dreamland and deciding to strike out on your own like this.

Sara: You know, it was something I had always wanted to do. Even when I published my very first book, which I published with Soho Press, and I’m glad I did. I published my first two books with them and they are still in print and they have just been wonderful to work with all these years, and I have so many buddies over there and I love working with them. But even with that first book, I was like, do I really want to give this away to someone else? I mean, theoretically, you still own your copyright, but good luck ever getting your US publication rights back once you sign it over to a publisher.

And I like the whole process. I found it interesting, I wanted to learn more about it. So there was kind of like the carrot of wanting to learn all of this stuff, wanting a new challenge in life. I like doing new things. I like failing at things. So if the whole thing comes out to be a fucking disaster, that’s ok, too, because it’s been a fun year pulling it together, and maybe what I’ll end up learning from this is why I never want to do it again. I don’t think so, but maybe, and that’s also totally ok.

So that was obviously this huge incentive of having wanted to do it for so long. And also, I’ve had really wonderful experiences, like Soho Press and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, and I have had less wonderful publishing experiences. And again, I felt like I’m just going to kick myself if I turn this book over to some branch of Simon’s House of Random Penguins, which is actually just a house where penguins walk around randomly and bump into each other once in a while, and they make a book.

Chris: That’s publishing.

Sara: That’s publishing. That’s all it is. It’s just these penguins and they’re all very random. “My name is Simon. I’m a penguin.” So I felt like if I gave it over to those guys and they didn’t do it justice, I would never forgive myself. And the other big motivation was I’m old and I’m cranky and I’m ornery and I want to do things myself. I want to make my own decisions. I don’t want to fucking argue with someone about a copy edit or a cover design issue or whatever. I want to hire someone—I can afford to; I’m very fortunate—and tell them, “This is what it is.” It’s not up to you to decide, it’s up to me to decide, because I’m a cranky old lady. That’s enough of a reason.

Christopher: I love that. We need more of that energy this year—just like, I’m going to take things into my own hands and make them happen.

Sara: I think we do. I mean, the publishing world is sort of the last place for this to take hold. Because obviously music people have always made their own records, always put out their own tables. My husband of 25 years is a musician, and he has always gone back and forth between small labels and putting out his own stuff. And of course, that was all pre-streaming because because we’re older folk and he doesn’t do as much now. So he would just get records pressed, get cassettes made, distribute them. Distribution is always the problem with independent media. That’s kind of the one big advantage of going with a big corporate entity.

Music has been far ahead of it. Film is a little bit different because it genuinely does cost quite a bit of money to make a movie, so that’s never going to be as DIY. Although you can find great examples in history of someone who just went out with an iPhone or something and shot a movie, it is a little bit different because there is a lot of actual equipment involved. In journalism, you have all these people going to their Substacks or their newsletters or whatever. I try to avoid the news as much as possible, but what’s been going on in terms of the economy, of people creating their own little universes in that area, is sort of exciting, inspiring. Podcasts really started from the ground up. They really started without the support of any big corporate media. And I think in books, obviously there’s a huge number of people who have started small presses or self-published and done really well with it, but there’s still a little bit of a stigma attached, I think, that you don’t have any other arts.

Christopher: Yes, self-publication does have this sort of like, “Couldn’t hack it, could you, kid?” No one says that to a podcaster, even though it’s an even less served arena.

Sara: That was another reason why this book of all the books was the one I decided to start my publishing house. I knew it was solid, again perhaps more accessible than my other books. And I was like, well, I am extremely vain. No one can come back and be like, oh, you couldn’t get this published, could you? Because it was sort of an obviously publishable book. Which not everything I do is.

*

So Many Damn Books

A blessing, a curse, a podcast. est. 2014. Christopher (@cdhermelin) invites folks to the Damn Library to talk about reading, literature, publishing, and trying to make it through their never-dwindling stack of things to read. All with a themed drink in hand. Recorded at the Damn Library in Brooklyn, NY.