Why Opera Will Never Die

Paul Morley on a Centuries-Old Art Form in Our Contemporary Age

Opera. Radio 3. Glyndebourne.

Debate: does opera matter? What is the future for opera? Still there?Article continues after advertisement*

The problem with the word “opera” is that even if you have never seen or heard one—and in fact have only come across it through the tatty realm of Simon Cowell and his camp, rich-man’s fascination with its sensual glamour and mystique—you will have a very definite opinion about what it is, and why it is not for you. Expensive, stuffy, kitsch, snobby, bloated, fancy. . . old. We’re fifty years after aesthetic autocrat Pierre Boulez proposed that the correct response to the perceived ossification of opera was to “blow the opera houses up,” but then he didn’t quite mean that, only that he too, with his usual irreverence, was trying to work out what to do with it, how to modernize it, keeping the usual repertoire, but developing new ways to present new forms. Nothing changes, including the desire to change.

Opera is one of those words that contains so much historical and symbolic weight and prejudice that you have to clamber through dense, thorny tangles before you even get to what it might actually be, and if there is anything really left, other than it being a segregated leisure pursuit for the entitled.

First of all, on my Glyndebourne day, a trip to the world-famous annual opera festival in a fine, unhurried part of England, which is part work, part dream, part detour into how the other half, well, 1 percent live, I take part in a live mid-morning Radio 3 debate on the program Music Matters about the relevance of opera. Relevance to who? may well be the question—for those to whom it is relevant, it is extremely relevant; for others, it is as relevant as needlepoint.

For the debate, I am surrounded by believers on the panel and believers in the audience, and I am worried that if I bring with me the full dynamics of my wariness about the current state of opera—as an evolving art form, if not a business, an epic token of civic pride, or a backdrop for architecture and morality—I will be more or less strolling into a church during Sunday service and shouting at the top of my voice that God does not exist. Or I will be telling wide-eyed young children on Christmas morning that there is no such thing as Santa. Worse, I would be attending a meeting of blinkered extremists clinging to their psyched-up, fucked-up fairy tales for meaning and purpose, and pulling apart the fragile basis of existence for those who consider opera the sublime, sacrosanct peak of all musical and artistic enterprise.

The problem with the word “opera” is that even if you have never seen or heard one, you will have a very definite opinion about what it is, and why it is not for you: expensive, stuffy, kitsch, snobby, bloated, fancy. . . old.

The angry cult followers carrying torches and expressing utter contempt for my thuggish monstrosity would perhaps turn on me, and send me into cold, dark exile where I will be forced to appreciate the enduring wonders of their faith. I can only return when I can sing something fiendishly difficult that requires me to rattle off nine high Cs and a couple of two-octave leaps while wearing heavy headgear the size of a small car and walking a flaming tightrope. It could be the beginning for an opera.

Or the beginning of a reality show. On the panel of articulate, defiant opera guardians slickly hosted by the always publicly confident Petroc Trelawny there is the hearty and venerable northern knighted bass (Sir John Tomlinson); the open-minded artistic director of the Danish National Opera (Annilese Miskimmon), committed to promoting opera as a modern, democratic and thriving artistic endeavour; the measured, eminently reasonable representative of the Glyndebourne management (David Pickard); the feisty, challenging founder of a country-house opera season that is perhaps dreamier and more luxurious than Glyndebourne (Wasfi Kani); and austere, unoperatic me, the awkward, ignorant tin-eared outsider, representing the voice of the suspicious, indifferent people who see opera as an indulgence for the wealthy, and/or a minority sport with arcane rules, and/or pure escapism for spoilt snobs and posh nerds, and/or sanctioned acid trips for the establishment, and/or a form of psychotherapy for those in the middle of a family feud or perhaps requiring lessons in fidelity, and/or an ornate embodiment of the ever-rigid class system keen on protecting its privilege. If this is a reality show, I am the favorite to be voted out first, complete with “Poisonous Paul” nickname, and there is a hum of suspicious nervousness about my position from the others. What nasty things am I going to say?

I am not actually against opera. I don’t think of it as being dead, any more or less than traditional politics, twentieth-century cinema, scheduled television, department stores, print journalism or pop music is dead. There are problems, but only the kind of problems all of us face as the essential structure of reality changes to accommodate the new spaces and circumstances being injected into our minds and packed into regularly delivered gift boxes by the technological and communication consequences of the computer and its damaged soul, the internet.

Opera is one of those words that contains so much historical and symbolic weight and prejudice that you have to clamber through dense, thorny tangles before you even get to what it might actually be.

Opera is, perhaps, undead, and this is something that is making me appreciate its twisted, decayed, ultimately perplexing beauty. It wasted away years ago in terms of where the rest of the world was, technologically, artistically and culturally, and the more accessible, crowd-pleasing parts fell off and grew into The Musical, ripe melody and unabashed sentiment in over-friendly hyperdrive, and the most melodramatic and raunchy storylines escaped into the extreme caricatures of everyday life that are television soap operas. But it kept going, in a weirdly shaped afterlife, where it was given financial and critical life support by those who consider it the clearest symbol of a civilized society and by those who think that inside the exquisitely layered fairy tales, dazzling showpieces, tongue-twisting language, acrobatic arias, heartbreaking laments and metaphorically deliberate over-the-top-ness there is the most exquisite theatrical balance of music’s heady abstractions and the power of the visual imagination.

I was once a devout atheist, but now I am more leaving behind an agnostic state and heading optimistically into the misty, Delphic opera country, where there be daft and divine stories so lavishly told and so clearly indestructible that in a Shakespearean sense—with complex life stories being packed into three-minute songs, moments of mischief transformed into explosive excess—there must be something to it other than it being a protected privilege for the accursed self-serving high and mighty. Perhaps I am battering past the word, the image, the offensive luxury status because I have decided that opera is one of those things so much in opposition to a world squeezed into the sense and moral fibre-shredding shape of Twitter and the light-headed, picture-book world of Instagram it must actually be, behind the bow ties, picnics, costumes and 19th-century rituals, a lonesome, lingering sign of intellectual life.

I am beginning to fancy the insular extremist elements, the convoluted belief system, the array of secret lovers, silver-tongued heroes, dark, brooding anti-heroes and untameable, spirited heroines, perhaps because I am reaching the correct stage in life. The abyss can be spotted a little too closely at the edge of my vision, and sometimes right in the damned center, and great opera never fails to take into account that for all the life and love, wit and whimsy, dexterity and transcendence, always there is death, and more death, and dreams beyond death, transformed into the most perfectly played death scenes, featuring a considerable expression of deep sadness, moist memories and drawn-out tender reflection on the lover being left behind. Opera is a golden, temporary production straining to the limit to suggest there is a light at the end of the tunnel of life’s miseries even as it knows there is no such thing; even when there is no hope, the sheer virtuoso of the performers and performances demonstrates how there must always be hope. Out of such intentions bizarre legends are created.

__________________________________

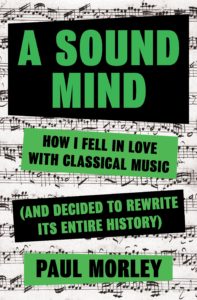

From A Sound Mind by Paul Morley. Used with the permission of Bloomsbury Publishing. Copyright © 2020 by Paul Morley.

Paul Morley

Paul Morley has worked as a music journalist, pop svengali, and broadcaster. He is the author of a number of books on music, including The Awfully Big Adventure: Michael Jackson in the Afterlife, The Age of Bowie, and Words and Music, along with two acclaimed memoirs. Morley lives in London.