Why It Matters How We Tell the Story of Sinead O’Connor

Allyson McCabe on the Power of Accepting that a Memoir May Contain Contradictions

Before I became a journalist, I was an academic cultural theorist. If you want to construct a scholarly argument, you cite other people. In journalism, it’s basically the same. But whatever academics or journalists claim, no matter how many times we do it, no matter how committed we are to sticking to the facts, absolute certainty does not exist.

When I was transitioning out of teaching at Yale en route to my current vocation, I took a brief detour through a journalism graduate program. There was this one professor we used to call “Sarge,” who was always blathering on about how the number-one rule of journalism was that you had to “get everything on record.” As my classmates scribbled away in their notebooks, I interrupted him. “What does that mean—get it on record?”

Sarge was flummoxed. “It means pull out your goddamn notebook, McCabe, and write down everything the subject says. That way when they say later that they never said it, you can pull out that notebook and say, ‘Yes, you did!’ When they threaten to sue you, you can pull out that notebook and say, ‘Go ahead, make my day!'”

Everyone nodded and laughed, scooping up Sarge’s pearls of wisdom. “But who’s to say they didn’t just make up what they told you? Or that you didn’t just make it up or distort what they said when you wrote it down?” I asked. “Then you get other people to talk to you,” Sarge replied, clearly exasperated, “and get them on the goddamn record, too!”

Everything in my lived experience up to that moment led me to reject this position as stubbornly naive, or absurd, the idea that THE TRUTH can be established through the steady accumulation of testimony, transcribed by a disinterested hand acting as judge and jury. Anyone who’s ever done an interview knows it isn’t a witness statement, and a memoir is even less so. Famous or not, people say the things they think other people want to hear and revise or hold back what they don’t. Contradictions and omissions aren’t simply a consequence of dissemblance or forgetting.

They’re the residue of feelings, not entirely erased, only obscured. Those who can “read” this half-hidden ink aren’t superhuman empaths who conceal their identities behind a mild-mannered facade to serve the noble cause of truth and justice. They’re just better at understanding that the truth appears as much in what’s not said as in what is, and in how it’s said, and when and where, and to whom, and why. Tuning your ear is totally different than sharpening your pencil. It starts with being in touch with yourself and being willing to risk exposing your own vulnerability to see or hear what someone else is trying to tell you.

Famous or not, people say the things they think other people want to hear and revise or hold back what they don’t. Contradictions and omissions aren’t simply a consequence of dissemblance or forgetting.This may be especially true for musicians, music journalists, and ardent music fans—all of us searchers. Thankfully for us, the celestial jukebox is a limitless lost and found. Think about your favorite songs, especially the sad ones, and why they resonate for you so strongly. It’s not necessarily the specific circumstances being described in the lyrics or the precise way the notes are arranged on the staff. Instead, it’s in the imaginary conversation you’re having with the artist, and how it helps you to connect in some way with your own experience.

That experience often indexes something you’ve lost, whether consciously or not. Songs can help us bring it back, recollect it, make sense of it, or at least learn how to live with its absence. Even though memory is never identical to the thing that’s been lost, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to remember. It means we should try harder. As time goes by, we may find ourselves further removed from one kind of truth (what it was) but edging ever closer to another (what it means).

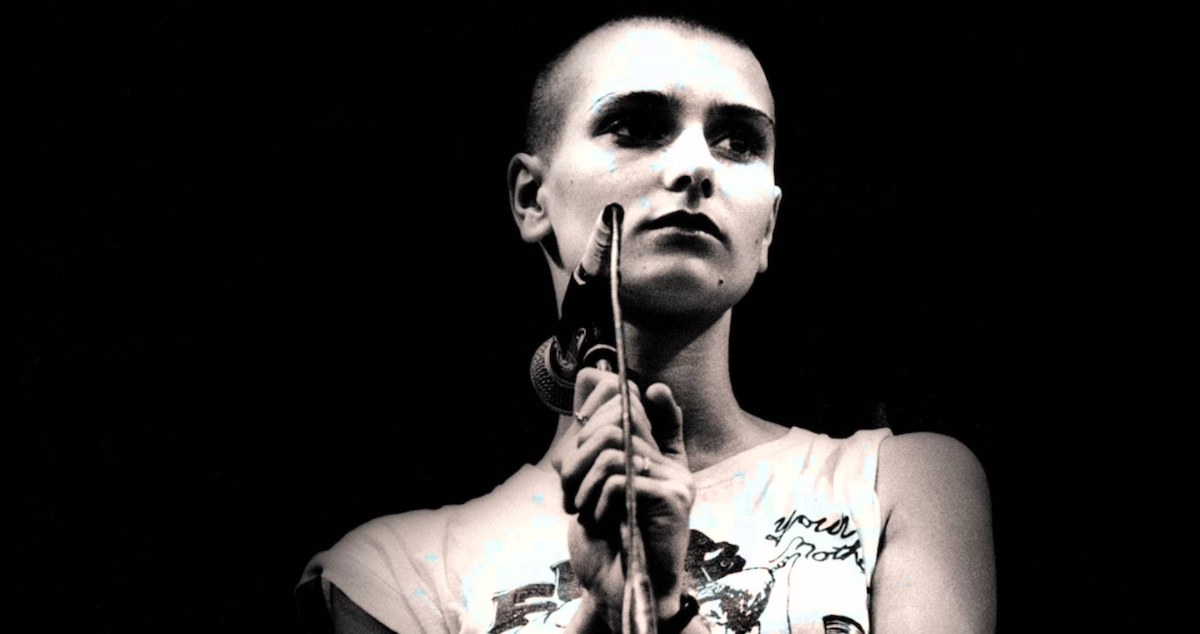

Going into my interview with Sinéad O’Connor, I knew it wasn’t going to be as easy as the interviews I’ve done before with artists such as Laurie Anderson, John Cale, or Thurston Moore—all big names and big talents, but not people I personally related to on the same level, not people whose music has made me weep so much or so deeply. I knew that O’Connor’s story wouldn’t be easy for me to tell, but that’s why it felt especially important for me to try.

Although my profile would be built on my interview with O’Connor, to bring context to her story I also interviewed feminist punk icon Kathleen Hanna and music critic Jessica Hopper. When I started putting all of the tape together, I assumed that the hardest part was going to be packing everything I wanted to cover into five minutes of airtime.

Changing the narrative about O’Connor proved far more difficult. The main point of contention was over using tape from her 1992 SNL appearance. Rather than leading with it, or bringing it in at all, I wanted the show host to refer to it only briefly in their introduction—something along the lines of:

“Sinéad O’Connor rose to the top of the charts with an unforgettable song [Clip of ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’]. Two years later a controversial appearance on Saturday Night Live dimmed the limelight. But O’Connor is out now with a new memoir, and she says that moment re-railed—rather than derailed—her career.” Allyson McCabe has the story.

Then, rather than reminding the audience that O’Connor was canceled, I wanted to show how and why she was canceled. That meant bringing in tape from Joe Pesci’s appearance on SNL the week after hers. Pesci goes after O’Connor aggressively in his three-plus minute monologue, at first referring to what happened fairly neutrally, as “an incident.” He then tells the audience he thought tearing up the photo was wrong, and explains that he asked someone to paste it back together. He holds up the reassembled photo and the audience applauds wildly. “Case closed,” Pesci says. But it wasn’t.

Pesci went on to implicitly blame Tim Robbins, who had hosted the episode, for “the incident,” for letting O’Connor get away with it. Then he remarked that she was lucky, “because if it was my show, I would have gave her such a smack.” Pesci held his hand to demonstrate the smack, and, again, the crowd broke out in applause—accompanied by cheers. Pesci took it in, smiling from ear to ear. “I would have grabbed her by her…by her….”

This is where I wanted to abruptly cut the tape. The word Pesci says next is “eyebrows,” a crack about O’Connor being bald, but of course the audience would hear the cut and think what he said was “pussy,” and think of Donald Trump. And that is exactly what I wanted them to think.

My point wasn’t that Pesci = Trump. I know that Pesci was reciting lines he probably didn’t write and expressing wiseguy viewpoints he may or may not have actually felt. (Pesci’s wiseguy character Vincent LaGuardia Gambini from the 1992 comedy film My Cousin Vinny was reprised in 1998, when he put out an album called Vincent LaGuardia Gambini Sings Just for You. It includes “Wise Guy,” a misogynistic gangsta rap song in which Pesci brags, in character, about how to treat “bitches.”)

What I wanted to show with my tape cut was that Pesci’s lines landed because the audience felt them. The point was not that he was a misogynist. It was that the audience, and by extension the larger culture, was misogynist.

In using that tape cut, I hoped to pose an implicit question: To what extent did misogyny mediate the way we saw O’Connor in 1992? And to what extent is it still woven—consciously and unconsciously—into our cultural scaffolding? This isn’t just a matter of perspective, male versus female. As a journalist, I’ve worked with men who acknowledge misogyny as a problem, and women who don’t. When it seeps into reporting it’s rarely overt—which is what makes it so powerful, and so hard to fight.

In this case, my editor (at that time) was a middle-aged cisgender heterosexual white man who would certainly identify himself as feminist. Nevertheless, he used words and phrases like “too suggestive” and “overkill” to urge me to dial Pesci down and bring more of O’Connor’s “incident” in for “balance.” Which one of us was right?

On the one hand, journalists are supposed to be neutral: just the facts, ma’am. That’s what we’re taught and how we’re trained. But deciding what tape to use and where to cut it are intentional choices with powerful ramifications. They deeply influence how we frame a story and give it context and meaning—and how you as the public see and hear it.

Therefore, our clash was more than a trivial difference of opinion. It was, on the contrary, a fundamental though unspoken disagreement. My editor wanted to include O’Connor’s performance to remind listeners about the controversy that she invited or even provoked. I wanted to include Pesci’s monologue to show how O’Connor was reprimanded and why.

Better, I think, for journalists to be transparent about these positions and to own them, rather than to pretend that one is objective and the other is biased. But deadlines are deadlines, especially in daily news, so rather than argue, I agreed to include brief clips from both tapes for “balance.”

However, I pushed for a new title, so it was “Sinéad O’Connor Has a New Memoir…and No Regrets” rather than the one the editor had floated, in which she “proclaimed” that she has no regrets. I also landed on the point that what O’Connor won’t do is apologize for surviving—which was far more suggestive than anything I would have been able to show with the tape cut.

In the end, I think my title reflected the main point of the story, but it wasn’t the whole story. Even if I had five years instead of five minutes, it would have been impossible to present a comprehensive biography. O’Connor explicitly denounced several unauthorized attempts in the early 1990s. (There are a couple of pre-SNL Sinéad O’Connor biographies floating around, such as Jimmy Guterman’s Sinéad: Her Life and Music [New York: Warner Books, 1991] and Dermott Hayes’s Sinéad O’Connor: So Different [London: Omnibus Press, 1991]). In 2012, she pulled out of a biography project that she had officially sanctioned after only six months.

Even in her own 2021 memoir, O’Connor acknowledged that there are significant challenges in telling her own story, namely, that her recollections are riddled with inconsistencies, gaps in her memory that she attributes to not being present for large chunks of her life.Even in her own 2021 memoir, O’Connor acknowledged that there are significant challenges in telling her own story, namely, that her recollections are riddled with inconsistencies, gaps in her memory that she attributes to not being present for large chunks of her life. She says other memories are private, or concern matters she would prefer to forget. In the foreword, she tells readers that she hopes her book will nevertheless make sense. If not, she advises us to “try singing it and see if that helps.”

I want to take that advice and honor it, to accept the inevitable gaps and inconsistencies, the difficulty of getting it right, and the impossibility of pure neutrality. I therefore plan not simply to recite O’Connor’s story, but to “sing” it bel canto, which, as she explains in her memoir, has nothing to do with mastering scales, breathing, or any other formal technique. Instead, it’s about singing in your own voice, allowing your emotions to take you to the notes, and allowing the notes to take you to the truest expression of the song.

Such an approach entails not only close reading but telling O’Connor’s story intimately, feeling the feelings myself, and letting the notes that are inside of me spill out onto the page from time to time, a bit like Fiona Apple’s duet with O’Connor in the “Mandinka” YouTube video. My goal, simultaneously easier and more difficult than conventional biography, is to illustrate why O’Connor matters, and to ground that assessment in the circumstances of her life and work and in mine.

As you read, I invite you to hold up a lighter, or a mirror, and sing along with us too, all of us piercing through the darkness together…journeying toward the kind of catharsis that only music can bring. Where better for us to begin than at the beginning?

______________________________

Excerpted from Why Sinéad O’Connor Matters, by Allyson McCabe, © 2023, published with permission from the University of Texas Press