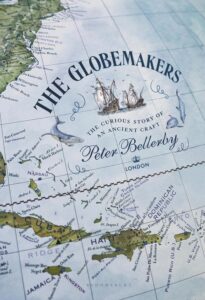

On the Artisanal Craft of Making a Globe

Peter Ellerby, the Founder of the World's Only Truly Bespoke Makers of Globes, On How It's Done

The simplest way to make a globe is to construct a sphere and paint it. The earliest globes would have been made of wood or metal, with the celestial or terrestrial map painted directly on by hand. Later, in the sixteenth century, hollow globes were made of thin sheets of metal which were then hand-painted. Mapping doesn’t lend itself to painting and lettering by hand, and cartography was in its infancy, so early painted globes were necessarily very inaccurate.

Later makers pasted blank gores onto the sphere to create a more forgiving canvas for the hand-painted map and lettering. These are called manuscript globes. The invention of the printing press meant that maps could be printed as gores. A silversmith or skilled engraver would etch a reverse map on copper plates before printing using a process known as intaglio, from the Italian word for ‘carving.’ In intaglio printing the etched plate is coated with ink, then wiped to leave ink only in the incised depressions, before being run through an etching press, in which dampened paper picks up the ink to create the printed image. Copper is a soft metal, so the plates lose their clarity relatively quickly; smaller print runs were therefore common. The effect, though, is very satisfying, with an intense character to the image. The globemaker then pasted the printed gores onto the globe and finally the painter would add color.

It was at this point that the globemaking craft became assimilated with the printing and publishing industry. Globes were after all now printed just like books, and since this time each edition has been referred to as a ‘publication.’ And as in book publishing, copying the map from a rival’s globe is plagiarism.

The golden age of the printed and then hand-painted globe coincided with the age of European expansion, reaching its peak at the beginning of the seventeenth century. In this period, as astronomical, geographical and cartographical knowledge developed apace, globemakers too were inspired to experiment and refine their art. In turn, the proliferation of printing presses made it possible over time to produce more globes at a less than exorbitant cost so they became more affordable to a greater number of people.

Nevertheless, the acquisition or commission of a globe was still the preserve of the aristocracy and the affluent merchant class. Because of the delicate and time-consuming nature of the work, a budding globemaker probably would have required considerable financial backing. Globes therefore were prized symbols of status and prestige.

Studying these venerable antique globes, it was striking to see how little the methods of manufacture had changed from the mid-sixteenth century until the twentieth century, albeit there is always a mystery about the exact construction and methods because so much is hidden under the surface – it was only in the last century that the rot set in. I knew that I had high aspirations but did not want to simply reproduce some sort of cheap faux-antique facsimile. Instead, my ambition was to produce a handmade globe that felt classic yet at the same time unusual, relevant and contemporary.

Bellerby Globes. shot by Tom Bunning for part of his ‘Crafted’ Series.

Bellerby Globes. shot by Tom Bunning for part of his ‘Crafted’ Series.

I come from a line of keen artists. My grandmother and my mother both loved painting with watercolors; my grandmother even taught it for many decades until well into her nineties. I have several of their paintings, although they are stored in my attic because, sadly, I just don’t share their enthusiasm for this medium; I don’t like the imprecision of the application, although more likely I don’t care for watercolors because I have never been very good at painting with them. However, in collaboration with the crispness of the cartography on a globe, watercolors acquire another dimension, allowing you to build up a rich color patina over many layers without obscuring the text. It really is a perfect match.

Watercolors were no doubt used on the finest old globes for this reason; indeed, I would go so far as to say they could have been invented for globemaking had they not been conceived centuries earlier than the first painted globe. Globemakers must surely always have planned to paint their globes with watercolors; they knew their creation would have pride of place in the purchaser’s house, so beauty was paramount. We might love the look of these old globes now, but when they were made, they were positively revered. Meanwhile Chiara Perano, a friend of Jade’s obsessed with astrology and mythology, had been designing a celestial globe, mapping the stars and drawing all eighty-eight constellations by hand. She also decided that my original basic cartouche was not suitable for her celestial globe, and she quickly came up with a much better design.

In the early years of Bellerby & Co., my approach to publicity and marketing was a little scattergun. Finding the correct person to contact at publications for editorial content was far from straightforward. I just fired off the odd email here and there, and occasionally the employee handling the info@ or press@ account would pass it on to the editorial team. Sometimes this miraculously resulted in some publicity for Bellerby & Co. globes, such as a tiny feature in House and Garden magazine.

Just as Chiara was finishing the first Bellerby & Co. celestial globe, the Perano Celestial model, David Balfour, the property expert on Martin Scorsese’s Oscar-winning movie Hugo, saw the House and Garden piece and commissioned me to make four globes for a scene in the film, one of which was to be a celestial globe in two pieces; they were going to film the scene in a clockmaker’s studio, so our globes fitted the bill.

The deadline for the Hugo globes was ridiculously tight – filming was due to start in June 2010, and I had to build in extra time for their in-house approval. And I was still learning many of the processes and practicing only on 50-centimeter globes; the commission was for a 40-centimeter celestial globe and three much smaller terrestrials. I worked into the night for weeks for next to nothing – I was just excited to be asked.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Globemakers: The Curious Story of an Ancient Craft by Peter Bellerby. Copyright (c) 2023 Bloomsbury Publishing. Used by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.