Why Is It So Hard to Write About Music in Fiction?

Anne Valente Would Rather Just Make You a Playlist

Although I’ve heard again and again that including pop culture in fiction will only serve to date a novel or short story, I love time-stamping my creative work. Why pretend that characters in a story set today aren’t in The Bachelor fantasy leagues? Fictional worlds aren’t meant to exist in vacuums, and for me, one of the greatest joys of working on a novel is figuring out the context of the world, and the particular pop culture each character might take in. But I didn’t realize until I was asked during an interview regarding my first novel, which was set in October of 2003, why I included the films and television shows each character watched, but didn’t include anything at all about each character’s favorite musicians and songs.

This observation took me by surprise: music has always been my most essential form of popular culture ever since I was small, so I had no idea why it was the only kind that never appeared in my fiction. I grew up on my parents’ record collection of Beach Boys and Sly & The Family Stone albums, sketching the LP interiors of Led Zeppelin IV and Every Good Boy Deserves Favour to hang on my bedroom walls. I’d learned the piano at eight, perfecting Bach Inventions and Scott Joplin ragtime by the time high school arrived. When I was five my parents took me to my first concert—The Who—which led to an entire adolescence of seeking out Radiohead and 10,000 Maniacs shows, bedroom walls papered with flyers from basement shows of Le Tigre, The White Stripes, Interpol, Built to Spill.

I adored music so much that before I became a fiction writer, I became a music journalist, writing weekly album and concert reviews. I loved this job, but soon found that I was writing reviews that felt distanced from how much I loved music. I didn’t know how to tell a reader how they might be moved by hearing a song, how to translate into pixelated text the experience of standing silent beneath stage lights among a spellbound crowd. I transitioned to food journalism where it felt much easier and far more accurate to mention that a restaurant’s sandwich included cilantro and garlic aioli, two definitive flavors that required no simile. And just like that, I never wrote about music again.

Maybe I will always be too close to music, to this kind of love, to feel that I am doing it any justice at all.

Despite my own lack, I’ve admired the ways in which other authors have handled music in their writing. Aja Gabel’s 2018 debut novel, The Ensemble, beautifully describes the competitive world of classical music through the perspective of the four musicians comprising the Van Ness Quartet. As these four friends navigate the successes and failures of their career together, the language of the novel richly integrates the glissandos and staccatos that two violinists, a violist and a cellist would inherently know. I appreciated the precision of Gabel’s novel, while also not knowing how to incorporate that kind of language into my own work in the absence of protagonists who knew music terminology. I’ve similarly admired Hanif Abdurraqib’s They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, a collection of essays that exquisitely explores the intersection of music, culture and politics. Abdurraqib’s work places the reader directly into the experience of attending concerts as disparate as Bruce Springsteen and Carly Rae Jepsen, and does so in a way that acutely conveys the emotional weight of sound. But I still couldn’t figure out how to apply what I’d learned from this book to my characters’ experiences of music in a fictional world.

This may be because, outside of works like Gabel’s novel, I’ve often found myself unmoved by the use of music in fiction. I’ve read novels or short stories where authors have incorporated song lyrics into a scene, passages that to me often felt like shortcuts to accessing the scene’s emotions. A track is playing on the radio of a parked car as two characters break up. A protagonist slides on their headphones and goes for a long walk. In such instances, the lyrics often break through the prose in short, italicized bursts, the particular lines seemingly chosen to comment upon what is happening in the scene. To me, this has always felt similar to the dream sequence in fiction where, as readers, we’re to take away a kind of symbolism without the author doing additional work of character development or thematic exploration.

This is surely unfair, since a song on the radio or an album blaring from the stereo has often meant so much more to me in my own life than an afterthought. I have sat in a parked car breaking up with someone as Cat Power’s Moon Pix billowed out from the dashboard. I have pulled on my headphones and walked for miles listening to Yo La Tengo because I was on the other side of the world from someone I loved. But when I’ve tried to incorporate these small moments that make up our lives into the fictional world of a character’s life, they fall short. I delete them. Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised by the observation that this is the case, that they don’t appear in my novels or short fiction despite a lifelong love of music. Maybe it’s easier to incorporate that one character adores Six Feet Under, that another watched every game of the 2012 World Series for love of the Detroit Tigers. Maybe I will always be too close to music, to this kind of love, to feel that I am doing it any justice at all.

I’ve created playlists for each book I’ve written to remember the patterns and rhythms, as well as the emotional tone of the sounds, that went into writing the words.

In writing my newest novel, I’ve come up against this predicament again. A road-trip narrative shared between two sisters, one would think there would be some mention of their road-trip playlists. Even more so because music shapes their lives, both sisters named after songs on each of their parents’ favorite albums. These albums form the soundtrack of their journey, with brief mention here and there of Heart’s Little Queen or Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, but in the end, I still couldn’t bring myself to reference specific lyrics or even particular songs; these albums are mentioned in passing, maybe half a clause at most. Rather than infusing the novel with the music the sisters are assuredly listening to for the entirety of their drive, I’ve instead created a playlist just for me of the songs I listened to as I wrote the book. Lord Huron. Sylvan Esso. Yellow Ostrich. Valerie June.

I’ve created similar playlists for each book I’ve written to remember the patterns and rhythms, as well as the emotional tone of the sounds, that went into writing the words even if the songs that mean something to me never make it to the page. After I wrote my first novel, a friend asked whether I’d been listening to a lot of hip-hop while writing the book. I had been. Across the entire year of writing that book was a playlist of Earl Sweatshirt, Kendrick Lamar, Anderson .Paak, and Run the Jewels. She said she could hear it in the syntax and cadence of the sentences.

Even if I still haven’t found a way to write music into fiction, and even if there’s a chance I never will, perhaps for now this is the best way that I can meld a love of music with the passion I carry for writing. My characters might not attend their first show standing in the loud silence of too-bright stage lights and booming amplifiers. They might break up in the quiet of a dim bedroom past midnight, the radio and stereo off. But if I am listening always to the music, as I have been since I first learned what a record player was for, then maybe the music is there in the language regardless. For now, I am comforted by the justice in this, that the music is still there behind every syllable’s beat, behind every single word.

__________________________________

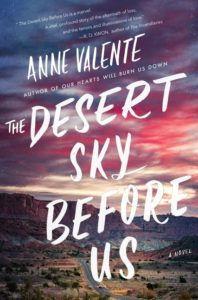

The Desert Sky Before Us by Anne Valente is out May 14, 2019.

Anne Valente

Anne Valente’s first short-story collection, By Light We Knew Our Names, won the Dzanc Books Short Story Prize. Her fiction appears in One Story, The Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, and the Chicago Tribune, and her essays appear in The Believer and the Washington Post. Originally from St. Louis, she teaches creative writing and literature at Hamilton College.