Why I Wrote My Memoir, a Letter to My Transgender Daughter, Under a Pen Name

“The protective force field is, in the end, imaginary.”

I’m writing an essay about pen names under a pen name because I wrote a memoir about identity under a pen name. What I found while writing with a pseudonym was a powerful protective force field that freed me as a writer, while also making me increasingly aware of the fragility of pen names. The protective force field is, in the end, imaginary.

Here’s the backstory. About ten years ago, my husband and I were raising our four kids in the Deep South. Our youngest, who was assigned male at birth, was adamant that her gender identity was as a girl. We lived in a relatively progressive college town and were overly confident that we’d be protected by this liberal bubble.

As our daughter transitioned to female pronouns and a nickname, someone made an anonymous call to the Department of Children and Families, accusing us of child abuse for supporting her. We quickly learned that the progressive bubble was an illusion, and, in this Southern state with decades of Republican-appointed judges, we could lose custody, which would have wrenched our family apart.

It was a terrifying time in our lives. I was both a mother in the thick of it and a writer taking notes; it was a coping mechanism. Once I started to see gender in new ways, I was amazed by all I’d missed—in nature, history, the brain, the body, in faith, religion, politics, pop culture… Gender was complex and rich and stunning.

But our story, the story of a family, felt impossible to tell. Years passed. And, as we moved into the Trump presidency with its strategic attacks against trans people, the story became more and more important. As trans people were villainized, Americans needed to know trans people and families with trans children. It seemed very clear that this was the story that landed with me, and it was my job to tell it and tell it well.

But how would I tell it without putting my family at risk?

First of all, I’d waited to tell this story until my daughter had an opinion on the matter; she was 13 when I first asked her about it. Did she want me to share it? Was she ready? She did, and she was. Now, as we near publication, she’s still unconcerned about the book because she believes in it. “It’s a good book,” she told me, “and it’s doing good for other people.” In addition to being smart and funny, she’s also straightforward, grounded, and good-hearted.

Secondly, the pen name felt like a clear and obvious choice for insulation. It would add immediate layers between my family and the reader. I needed those layers as a mother who wants to protect her family, but also as a writer moving into very personal and emotional terrain.

I was both a mother in the thick of it and a writer taking notes; it was a coping mechanism.It was hugely liberating to write the story with anonymity. I wonder now, if I hadn’t written it under a pen name, would I have been so raw and honest? My creative process benefitted from the pen name so much that I started to wonder: should I start suggesting that other writers try writing their first drafts under pen names, too?

Of course, there’s a long tradition of pen names, especially for women writers, a tradition that often entwines with gender identity and expression. The Bronte sisters first published under male pseudonyms. There’s George Eliot and also George Sand, who often wore men’s clothing. According to the scholarship of Peyton Thomas, Louisa May Alcott not only used the male pen name A.M. Barnard but also wore men’s clothing and expressed ideas around gender identity that may well indicate a transgender identity, at a time when there was no vocabulary for being transgender. “I am more than half-persuaded that I am… a man’s soul put into a woman’s body,” Alcott wrote.

Notably, another author who belongs on this list of pen names is Robert Galbraith, the male pseudonym of JK Rowling, whose statements about the transgender community have caused a lot of pain in our family and for countless others.

I’m not the first to figure out the freedom of the pen name—and the risk of it being ripped away. By the time I started writing the memoir, the identity of the famous writer Elena Ferrante had (allegedly) been exposed, and Claudio Gatti, the person who wrote the exposé, was roundly criticized.

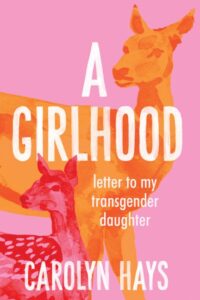

My creative process benefitted from the pen name so much that I started to wonder: should I start suggesting that other writers try writing their first drafts under pen names, too?Ferrante has talked about why having a pen name was so important to her. It allowed her to “concentrate exclusively and with complete freedom on writing and its strategies.” I needed that concentration and freedom. Writing what would become A Girlhood: A Letter to My Transgender Daughter was the hardest, most important task of my writing career. I needed to get it right, not just for my daughter’s sake, but in hopes that it would help others.

Once the book was finished and submitted to editors, I was intensely aware that the layers might not hold. What if I’d believed in the pen name as a powerful protective force field the same way I’d once, naively, put faith in the protective powers of the progressive bubble surrounding the town we lived in while in the Deep South?

We had to accept that people might choose to dig around and reveal our identities. I now live in this strange existence where I hope the book gets to the people who need it, who can be helped or moved or even changed by it, but that it doesn’t actually become a Big Book. In my entire life as a writer, I’ve never wished so hard for a book to succeed and also wished against it.

After the case was dropped, my family moved to the northeast where there were laws in place to protect our daughter. I think of the pen name the same way I think of those anti-discrimination laws. We had to have faith in those laws—and they were crucial to our safety—but they couldn’t perfectly protect our daughter either.

In my entire life as a writer, I’ve never wished so hard for a book to succeed and also wished against it.Now, as the publication date looms, I have sleepless nights; all the old fears have risen to the surface. But our story has only become more urgent, and my commitment to the telling of it has deepened.

The threat to our family, which seemed like a bizarre nightmare, has become a political strategy targeting the trans community. Earlier this year, by executive order, Texas governor Greg Abbott codified into law that any parents who support their trans child should be investigated for child abuse by the Department of Family and Protective Services. The executive order is going through the court system while families like ours make the excruciating decision to stay and risk losing their child, or leave the place they’ve called home. Some families, of course, for various reasons, can’t move, and have to live under the State’s constant threat.

The memoir has already come out in a few countries overseas. Advanced copies are making their way to readers and reviewers. And we’re starting to see the book get into the hands of people who need it most. We’re hearing their stories, reflected back to us; and, despite the risk, their stories are becoming the reward.

__________________________

Carolyn Hays’s A Girlhood: A Letter to My Transgender Daughter is forthcoming from Blair.