Why I Wrote a Novel Full of Secondary Characters

María José Ferrada on Precarity, Loss, and Traveling Salesmen

Translated by Elizabeth Bryer

It must have been the end of the eighties when I accompanied my father, a traveling salesman, on one of his trips down south. This was in Chile, and we were in one of the small towns he visited regularly. I don’t remember if he was selling detergents at that stage or perfumery products, but I do remember that we were seated, each of us cradling a coffee, when I asked whether he had noticed that the hardware store had closed down. I still remember its name, La Paloma, and that its owner was always the one serving customers. He was a French immigrant who had retained his accent even though Chile had been his home for more than fifty years.

“We’re well and truly fucked,” responded my father, with an equanimity that was typical of him, downing the last of his coffee. Accustomed as I was to his curses, I’m not sure why I paid this one special attention. “We’re well and truly fucked,” I repeated. I must have been ten. My father, a little over forty.

Fifteen years went by before I understood what he meant. In those fifteen years I saw how neoliberalism, adopted in Chile at the end of the seventies, gobbled up the small businesses that my father’s trade depended on.

When I realised that everything was disappearing before my eyes, I knew I had to write a novel about what it had meant to live that life. There was the precariousness, but there was also the happiness of travelling the highways, cursing those who hadn’t purchased anything from us or, if we managed to close a sale, enumerating the treasures we would buy with the tiny commission we had made.

I speak in the plural, and in third person, because even though back then my job was limited to waiting for my father, either outside in the car or walking laps of the main square of whichever town we found ourselves in, I always felt like just another member of the strange, foul-mouthed family that the traveling salesmen made.

When I realised that everything was disappearing before my eyes, I knew I had to write a novel about what it had meant to live that life.

I owed them a novel such as this, because never again have I laughed so much—or inhaled so much cigarette smoke—as when I listened to the tales they told at day’s end in those shabby hotels, which never managed to shelter us from the cold.

I had a dream that my peers—I still mean the traveling salesmen—held the novel between their hands and recognized themselves in it. In my dream, time was acting strangely. The traveling salesmen were there, with their sample cases and their ludicrously shiny shoes, and they were turning the pages, while I was still a girl and was watching their faces, waiting for some sign—a nod of the head or a laugh—that would tell me that I had told the story right. That, and for them to comfort me in some way, to tell me that it wasn’t true, our world hadn’t come to an end; I was just catastrophizing, like always.

It took me three years to write it, because as I made progress describing the disappearance of my father’s trade, other disappearances kept showing up: bonds, ways of ordering and understanding the world that are only of use when you are a child and, finally, bodies. Because How to Order the Universe is a story that takes place in the towns and cities of the south of Chile in the years of the military dictatorship.

The first person to read the manuscript was my father. I told him that, while I wouldn’t make any changes for him, I wanted him to see it before it became a book. He told me it reminded him of things he had forgotten. He also said that never had he imagined he would appear in a novel. “A novel full of secondary characters,” he told me. “Something like that,” I said.

I know that some of the salesmen read it because they called me to thank me for dedicating a character to them, and to tell me that I had gone a bit far when it came to revealing the tricks of the trade. They also told me that I wasn’t to worry, that they would take care of visiting the bookstores of their respective cities to ask after the book and request copies, pretending they would buy it. A sales strategy that, old though it was, never failed.

__________________________________

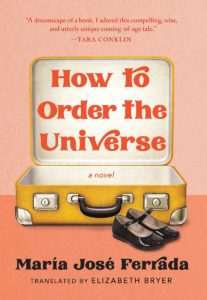

How to Order the Universe by María José Ferrada (trans. Elizabeth Bryer) is available now via Tin House Books.

María José Ferrada

María José Ferrada’s children’s books have been published all over the world. How to Order the Universe has been or is being translated into Italian, Brazilian Portuguese, Danish, and German, and is also being published all over the Spanish-speaking world. Ferrada has been awarded numerous prizes, such as the City of Orihuela de Poesía, Premio Hispanoamericano de Poesía para Niños, the Academia Award for the best book published in Chile, and the Santiago Municipal Literature Award, and is a three-time winner of the Chilean Ministry of Culture Award. She lives in Santiago, Chile.

Elizabeth Bryer is a translator and writer from Australia. Her translations include Claudia Salazar Jiménez’s Americas Prize–winning Blood of the Dawn; Aleksandra Lun’s The Palimpsests, for which she was awarded a PEN/Heim Translation Fund grant; and José Luis de Juan’s Napoleon’s Beekeeper. Her debut novel, From Here On, Monsters, is out now through Picador.