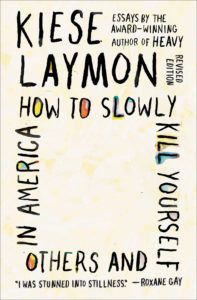

Why I Paid Tenfold to Buy Back the Rights for Two of My Books

Kiese Laymon on Revision, Radical Friendship, and Community

Yesterday, I attended a virtual book club where Heavy: An American Memoir was being read. When I clicked the link to join the Zoom, I saw the faces, necks, and shoulders of seven beautiful pixelated Black women from as far west as Las Vegas and as far east as Long Island. I assumed from their familiarity they’d all gone to school together. They told me they just met at the beginning of the pandemic. The seven women were initially part of a 2,000-person book club that shrank to a hundred people for reasons no one would explain. Eventually, the seven women decided to create their own virtual book club.

Ten minutes into the conversation, after everyone had checked in, the organizer of the Zoom said they’d all recently met in person, gathering in Chicago a few weeks ago.

I was confused.

“A few weeks ago,” I said into my greasy computer screen, “we were still deep in COVID.”

“We quarantined for two weeks at home,” one of the women said. “Then we all went to Chicago and stayed with the organizer in the middle of the pandemic.”

“Wait, wait, wait,” I said. “Y’all risked it all for a book club?”

The seven women looked at each other and filled that space with full-bodied laughter, wet eyes, and smiles that rocked back, back, forth, and forth.

They risked it all for the radical possibilities of friendships forged in books.

I understood.

*

I was 28 years old, without a literary agent, when I was offered my first publishing deal. Though I’d never met the editor interested in my work, I assumed all editors wanted to be friends with the writers whose work they respected. I knew I desperately wanted to be friends with any editor who respected me.

I realized, nearly a decade too late, that this editor was never my friend.

Shamefully, I would repeat this pattern of assumed friendship in publishing with folks who, to their credit, never called me a friend. The only thing I did remotely well during my failed relationships with publishing was read, write, and reread. Rereading The Bluest Eye taught me how to value what I’d been told I could not see. Rereading The Fire Next Time taught me how to value the messy work of love in America. Rereading Going to the Territory taught me that “human being” was a verb. Rereading Kindred taught me to will my husky Black body beyond spectacle and into a generative space that needed to look back, back, forth, and forth.

They risked it all for the radical possibilities of friendships forged in books. I understood.

Not only had every friendship in my adult life been forged by books, I literally found radical friendship in the authors and texts I imaginatively met. Pecola Breedlove, Nicholas Scoby, and Esch were my best friends. The first and last lines in “The Cask of Amontillado” were my shady white friends. Toni Cade Bambara and Richard Wright were my super oldhead friends. I walked with my friends, talked with friends. We spent tens of thousands of hours in each other’s homes, wandering around each other’s guts.

I started this book the week after my uncle Jimmy died in July 2007. It was initially called On Parole. I wrote half of the essays for the book on my back from a faculty apartment in Poughkeepsie, New York. The essays were posted on a blog called Cold Drank. I started writing to my uncle Jimmy because I thought his was the only spirit who might understand the contours of the fiery tent of shame I’d made for myself. I wanted “We Will Never Ever Know,” the essay directly addressed to my uncle, to end the book. I wanted the book to read backward, from now to its origins.

We had one problem. I was terrified of now. Now looked ugly, like me.

While my relationship with paragraphs, chapters, and dead authors was getting more intimate, I was getting worse at being human. One cold night in New York, in 2009, a friend I loved told me that I was precisely the kind of human being I claimed to despise, the kind of friend who fed off mangling the possibilities of radical friendship. I defended myself against this truth and really against responsibility, as American monsters, American murderers, American cheaters, and American friends tend to do, and I tried to make this person feel as absolutely malignant as I was. Later that night, I could not sleep, and for the first time in my life, I wrote the sentence, “I’ve been slowly killing myself and others close to me.”

The first draft of How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America ended with an essay called “You Are the Second Person.” It was the only essay in the book unafraid of assessing from whence the actual writing on the page came. I never wanted “You Are the Second Person” to end the book, but I hadn’t willed myself to write rigorously about where and why I was in the world after my publishing failures.

Not only had every friendship in my adult life been forged by books, I literally found radical friendship in the authors and texts I imaginatively met.

I wanted the book to be a site of the catastrophic and pleasurable, the intellectual and the everyday, the public and the private, the awkwardly destructive and the wholly sublime. Instead of imagining standard “literary” audiences, I knew that I wanted to question traditional literary forms and trajectories by writing to friends, and sensibilities, who didn’t like to read, and friends, and sensibilities, who were paid to read for a living. I knew that I wanted to create work that explored, with colorful profundity and comedy, the reckless order of American human being, especially since so much of the nation was in a dizzying rush to crown itself multicultural, post-racial, and mostly innocent. I wanted to create a book with a self-reflexive musty Mississippi blues ethos. I wanted a book that could be read, and really heard, front to back, back to front, in one sitting. I wanted readers to generate art in response to this text while working with the essays at being better lovers of those we profess to love. The hardest part, of course, is that I wanted to become a person, not just an author, worthy of forgiveness and risk from literary and literal friends.

Though I was 42 years old when I approached the publisher about buying this book back, revising and reissuing it the way I always imagined, far too old to believe in the sanctity of professional friendships, I still believed that the people with whom you collaborated on art were friends. I still believed that the white folks we made money for owed us friendship, or at least relationships with a pinch of integrity. I was still begging white folks in publishing to be better to me than I was to friends I claimed to love.

Today, in the midst of the most death-filled summer of our lives, I bought my first two books back from the publisher so I could revise and reissue them. I paid ten times what the publisher initially paid for the books. I’m thinking a lot about debt, reparation, vengeance, residue, and the tendrils of humiliation caused and withstood. I am thankful to have made it to a place where I will never waste my words on anyone in publishing whom I burdened with the hope of friendship. As painful as the publishing experience has been, I have radically loving friendships with the folks whom I currently collaborate with on art.

Revision did that.

In this revision, I start in Mississippi, where I am actually writing in 2020, and I hope that the reader works their way back to the beginning which, for me, is always the end. The middle though—all those middles of all those essays and all those real and imagined friendships—is where we find the guts. I hope you find radical possibilities and guts galore in this revised piece of art. Writing the first edition of How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America brought me back to Mississippi, literally and literarily. Coming home to Mississippi had given me the space to finish Heavy. In the revision of this book, I write from Mississippi about our current awakening.

I wanted the book to be a site of the catastrophic and pleasurable, the intellectual and the everyday, the public and the private, the awkwardly destructive and the wholly sublime.

The movement of the essays is painted in regret and revelry. All the pieces in this book are differently shaped, paced, and greased with orange-red odes to my Grandmama and her generation of Black women in Mississippi. The book moves backward, in a counterclockwise migration, from North Mississippi, to Upstate New York, to Pennsylvania, to Ohio, to Central Mississippi. It marches from the wandering weirdness of middle age, to lonely collaborations born of saccharine dreams, to the toxicity of American responsibility heaped on Black children and elders. These essays want us to have radical friendships rooted in courage and healthy choices. When I’ve had courage, I often lacked the healthy choices. When I’ve had healthy choices, I often lacked courage. Ending unhealthy transactional relationships and opening ourselves to radical possibilities is one way we effectively heal ourselves and others in America. Securing the rights to my books, revising them, and publishing them the way they want to be published are the most loving acts I could do for my work, my body, and my Mississippi.

I hope no writer alive ever has to pay ten times what they were paid to secure the rights to a piece of art that helped them, and others, accept life. If nothing else, I hope every writer alive never ceases believing in the rugged majesty of revision.

I wanted it all to stop. I needed it all to stop. I revised. I revised. I stopped it.

I am proud of myself for not giving up, for accepting help, for not drowning in humiliations of yesterday and the inevitable terror of tomorrow. That is the hardest sentence I’ve ever written. This is How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, one of the many radical possibilities of friendship forged in books.

__________________________________

From How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America: Essays by Kiese Laymon. Used with the permission of Scribner. Copyright © 2020 by Kiese Laymon.

Kiese Laymon

Born and raised in Jackson, Mississippi, Kiese Laymon, Hubert McAlexander Chair of English at the University of Mississippi, is the author of the novel Long Division (soon to be re-released from Scribner) and the memoir Heavy.