Why I Saw The Bad News Bears Ten Times in the Theater as a Nine-Year-Old Boy

Thomas Beller on Losing His Father and Finding Him Again and Again in a '70s Classic

The Bad News Bears was released in movie theaters in April 1976. It was a surprise hit. One possible reason for its success was that it was a summer of weak competition, in box office terms. The two other successful movies of the summer of 1976 were That’s Entertainment, Part 2, a movie composed of snippets from lots of old movies, and All the President’s Men. Another possible reason for its success were people like me: I saw The Bad News Bears ten times. This in itself was not so unusual. Jaws had come out a year earlier. Star Wars would come out the year following. It was suddenly customary for people—eleven-year-old kids, especially—to see movies over and over in the cool darkness of a movie theater.

Repetition is connected with ritual and, by extension, with reassurance. Babies and little kids, upon seeing something that amuses or pleases them, will call out, “Again!” At least mine did. But at the age of eleven I wasn’t all that little. And, I assume, the audience for the movie went beyond eleven-year-olds and their parents. Is it possible that there was some feeling of the tectonic plates moving deep down beneath America that made people yearn for the reassurance of seeing a tried-and-true movie again and again?

In my own life there was nothing metaphorical about the moving of those tectonic plates. The earthquake had struck in 1975, with the death of my father. One obvious reason for my interest in the movie, then, was that Walter Matthau reminded me, a little bit, of my father. Not in any explicit way—my father wasn’t the cranky, alcoholic ex-minor league baseball player who drove around Los Angeles with his pool cleaning equipment in the back of his Cadillac convertible played by Matthau. He was a doctor, trim, somewhat athletic, even. But there was something about the coloring of Matthau. The dark helmet of hair. The fatalistic humor. Am I just talking around the word Jewish? Maybe. But it went beyond that. At any rate, one possible explanation for my intense interest in the movie was the echo of my father in Matthau.

I was rooting for the Bears, for Matthau. Identifying with them. But what exactly was I identifying with?

I was told my father was very handsome—by my mother, of course, but others too. A woman named Jane Moss, who knew him from college at the University of Iowa. “Terribly handsome,” Jane told me, “and shy.” Her roommate was in love with him, she said. They’d had a falling out over it. Her roommate was engaged to be married to another man. But she was in love with my father. And she was an anti-Semite. This came out in pieces over the course of years—first that she had gone to college with him, and then that she knew him. And then years later, when it occurred to me to ask her direct questions. And even now, years after those conversations, new information arrives by virtue of it dawning on me that my father and Jane were in college during World War II, for example.

Jane was wispy, white-haired, ethereal, lovely. Every year or so I would call her, ask her questions, wanting to hear the story again. She’d been in a sorority, she explained, and her roommate had blackballed a girl who wanted to join because she was Jewish. Furious about this, Jane quit the sorority.

I forgot to ask Jane one important detail about this roommate who was in love with my father in spite of the fact that he was Jewish—and an immigrant, no less, a refugee!—in spite of the fact that she was engaged to someone else: Namely, had my father had the slightest idea of this girl’s love for him? Had they interacted in any meaningful way? Or was my father simply a crush?

So, he was shy, and handsome. There are photographs that attest to the latter, one from his early twenties, another from later, in his forties, a full-on adult with the weight of responsibility visible in the lines of his forehead. Handsome, yes. But it’s mostly the monkey-like qualities I see; for me he is always making a face, cross-eyed, making me laugh, the thick black hair a bit low on his forehead, like one of the lower primates. As far as I know he never made a point of exercising. He wore elegant suits, drank coffee with a certain style, smoked cigarettes, read the newspaper, sometimes all at once. The whole package—the coffee, cigarettes, suits, newspapers—surely a legacy of his youth in Vienna. He was a European guy.

He left Vienna when he was just sixteen years old, or so I thought for most of my life until I began to look into it and discovered that he was just fifteen when he left. And relieved as he may have been to make it to America, he was never an American. It’s so tempting to think of his having escaped the Holocaust as some sort of triumph. But can there be any feelings of triumph when society—your society, speaking your language, in your country, your city, your neighborhood, your neighbors!—had tried to murder you? Had made you kneel in the street to scrub the sidewalk with a toothbrush? And that you had been forced to flee your apartment on the long narrow street at the end of which was a newsstand where you always bought candy for your friends? This detail about my father sharing his candy was one of the pearls I wrested from my otherwise unforthcoming uncle, my father’s older brother, when he was ninety-two, just before he died.

At some point in my childhood, when I was around seven, and after what seemed like years of interminable drives through the boring countryside, my parents bought a country house, and it was there that I witnessed my father exercise in the manner of a country farmer. I was always eager to help. Once the two of us set about attacking weeds along the side of the house, each of us with a big scythe. We stood near each other, madly whacking at the weeds, cutting clear the whole side of the house. This image has stayed with me vividly, intact from the moment it happened—the silence, the cadence of our swinging arms, the thwacking sounds, the steady breathing. Only now, a father of a boy who is seven, do I wonder: Why were there two scythes? Had he bought them with the idea we might have such a moment?

*

I never knew he was sick. Not until that last year.

I defend my parents’ decision to withhold this bad news from the third member of the household on the grounds that, after the initial bad news, when he was diagnosed with cancer, and the ensuing round of chemo and radiation, he did get better. Maybe he was a little less robust than he might have otherwise been, but…better. He had a good seven or so years after that.

And, surely, if the man was well enough to scythe for an hour in the summer heat, then he didn’t need to advertise his illness to his son. This factual omission extended as well to his professional life. He was a doctor, a psychoanalyst. His social life was composed largely of people who were his colleagues at the Columbia Psychoanalytic Institute, where he taught. He didn’t tell anyone there, either.

I am not inclined to second-guess this choice, which was surely a product of the time in which he lived, when cancer was an almost unmentionable condition. I look at my own children and think of what it must have been like for my parents to live with such knowledge. I feel pity for him, a very strange thing to say about a man I last saw when I was nine years old, a father in every important way—a protector, one who returned from trips to other cities bearing gifts, the mystery of his combs, pipes, cigarettes, his razor, the thick white shaving cream on his face, the peering into the stock market tables in the newspaper, someone my mother loved with an intensity that she must have thought, on some level, could keep him alive.

Pity that he had to look at me knowing he had this secret: that he might not live to see me grow up. But that doesn’t fully pinpoint what it is I pity him for. It’s the degree to which he would have been able to fathom the pain his child would feel at his loss. He would have been all too capable of gaming it forward, seeing the possibilities for turmoil that arise when a kid loses their parent, their father. Sometimes I wonder to myself why he worked so hard, spent so much time in his office, and didn’t make as much time as possible to spend with me while he could. The answer, I think, has to do partly with the conventions of the era, when fathers were not expected to spend a lot of time with their kids. But perhaps some of it had to do with precisely this feeling of poignancy that seeing me would have engendered in him. Were I in his position—and maybe that is the phrase with which adulthood commences—I would look at me, the kid, with tenderness and anguish, thinking of everything they would have to deal with in my absence.

I am not inclined to second-guess the way he lived with his cancer for the seven or so years he had it. Nor do I doubt the wisdom of my parents’ decision not to tell me about it. And I also accept Elizabeth’s theory, that I must have been absorbing the truth through osmosis.

*

But then, of course, it happened. In 1975. The earth opened and swallowed my father, literally. Everyone around the grave threw a flower into it. Broke it at the stem. I chose one already broken for fear I would be stuck struggling with a flower stem, unable to tear off the bloom. Later, from the top of a steep and very beautiful hill where he is buried, everyone came down to the road except my mother and a friend of my father’s named Arnie. After a while Arnie helped her off her knees, and they, too, slowly made their way down.

It was just my mother and me now. Which is how it came to pass that the following year I saw The Bad News Bears for the first time with my mother, of all people. In those first couple of years after my dad died, I was constantly dragging my mother to things that she would not have otherwise gone to. Baseball games, for instance. And certain movies, some that were less appropriate, not for her, but for me, for us, such as Barry Lyndon. I am tempted to say that her judgment was a little clouded by the overwhelming responsibility of raising me alone. It was hard to know where to draw the line. Also, she was a foreigner, unaccustomed to American life on some basic level though fluent enough in its New York, émigré permutation. There was no father who could be consulted when I made demands. No other adult who could play bad cop to her good cop, or vice versa. Just my incessant requests to go do things and see things.

Now that I am raising two kids with the help of a very present, alert wife, I think it may be that the position of parent is one that requires a constant struggle for balance and perspective in the face of the barrage of pleas, needs, and requests of the child, particularly if your children are as willful as mine are, as willful as I once was. I suppose just about all children are born geniuses of lobbying and negotiation.

So, she took me to see The Bad News Bears. I loved it. To my surprise she enjoyed it, too, so that when I asked to see it again, it didn’t seem all that hard for her to agree. She may even have seen it with me a third time. After that, I was on my own. At a certain point the movie was playing in only one theater in the city, a place across town, on Third Avenue. I negotiated rights to make the pilgrimage solo on the cross-town bus—for by then I had exhausted my supply of friends willing to see the movie—provided I came straight home afterward. I sat in the theater by myself, eagerly imbibing the whole spectacle, laughing and feeling some other hard-to-name feeling. It was a private communion. I was rooting for the Bears, for Matthau. Identifying with them. But what exactly was I identifying with? Being bad at baseball? Being fat or an immigrant or full of self-pity for one reason or other. Or, in the case of Tanner, a kind of mini Archie Bunker, simply seething with anger at everyone always?

I found a clue as to what quality I might have been responding to when, years after the fact, I read the New York Times critic Vincent Canby’s review. “At 12 she has a peculiarly unsettling screen presence,” he wrote of Tatum O’Neal, “looking, as she does, like a pretty child but possessing the reserve of someone who has been through the wars.” About Jackie Earle Haley, the delinquent, athletic biker kid who is, in essence, O’Neal’s love interest, he wrote, “There is something about him that makes you suspect he may actually be an aged munchkin, exiled from the land of Oz for crimes that must remain unspeakable.” Both of these fanciful descriptions evoke qualities that, at the dawn of my own delinquent years of exile, must have resonated.

When the sequel, The Bad News Bears in Breaking Training, came out a year later, I went and saw that one eleven times. It’s true you can’t go home again, but this came very close. Breaking Training was pretty terrific in its own right; it was written by Paul Brickman, who went on to discover Tom Cruise in Risky Business and make many other movies, though it lacked Walter Matthau, replaced in the role of coach at first by a tyrant (“Never assume,” he scrawled out on a blackboard in front of his blinking team, “or you will make an ass out of u and me”) and then a young, athletic coach played gamely by Bill Devine. It featured some amazing footage from the Houston Astrodome, too, including a chase scene that made me scream with happiness every time I saw it. Mostly it featured all the same kids (minus Tatum O’Neal) and even had Jackie Earle Haley (about whom more in a minute). But without question, it was not as good as the first one.

The last couple of viewings, I recall, were made mostly with an eye toward beating my previous record of ten. I was keeping score. Once I got to eleven I could rest. They made one more movie, in 1978, The Bad News Bears Go to Japan. It was horrible. I barely lasted through one sitting. But for two seasons, 1976 and 1977, there was something going on with The Bad News Bears and me.

*

The 2005 remake of The Bad News Bears does not concern me, except that it was released not too long after I met Elizabeth, and prompted the original movie to rise to the surface of my consciousness. I asked her to watch it with me.

Perhaps it was this feeling of paternal resurrection, or at least redemption, that had me coming back to the theater again and again.

Though I was moved by the film while watching it with her, it didn’t move me nearly so much as another film from around that same era, Breaking Away. The two movies share similar themes of castoffs and fatherless kids; their plots are both organized around a sport and its rituals; and both culminate in a contest between the underdog heroes and the seethingly entitled favored sons. There is a father in Breaking Away, a flustered, ineffectual father who sells used cars for a living. Played for comic relief, he is baffled by this son of his who attends college and, more perplexing yet, is suddenly obsessed with Italy and cycling. In the middle of the movie, at the part where the dad has a heart-to-heart with his son about how he had helped quarry the rock that built the university that was now the province of the asshole frat boys against whom his son was going to compete, I started to cry. Then I was sobbing.

I wept so copiously that there was time to laugh about it through tears, apologize, pull myself together, almost, only to break down again, with Elizabeth alternating between concern and affectionate amusement, stroking my back and shoulders while saying, over and over, with fluctuating degrees of alarm, “Oh honey.” I sobbed some more, and it wasn’t funny. And then it was funny again. This outburst was mysterious at the time and remains mysterious. My only thought was that I had experienced these two movies in the first sharp years of fatherlessness, and I was now watching them as I approached marriage and, out of sight but coming into view, fatherhood. And here was this well-intentioned father giving a pep talk to his son, talking to his college-age son as a peer, man to man, the kind of talk I never had with my dad.

*

The Bad News Bears begins as follows: We see sun-struck sprinklers pulsing over a Little League outfield. There are long shadows on the ground. Somewhere in suburban California it is early morning. This landscape is completely foreign to me, as a New Yorker, and yet the sunshine has an elegiac glow that is my favorite light, and the sprinklers are like a baptism, not that I have ever had this done. Seeing them, the viewer is enveloped in an almost narcotic glow as you settle in.

We see kids doing drills in the infield, prompted by an adult voice, a coach, in whose faintly heard exhortation one can sense all the micromanaging passion for winning that, in time, will come to be revealed as both deeply screwed up and also highly prescient about where the culture of parenting in America was, even then, headed.

Into this pastoral scene of modern irrigation and baseball training sweeps Walter Matthau, driving a big, old, shambolic convertible, well past its prime but, like its driver, still possessing more than a bit of charm. His face, while not exactly handsome, nevertheless has a certain charisma to it, a monkey-like instinct for comedy. Reassuring, too, for me, is the thick black hair that sits a bit low on his forehead. He reaches back to the cooler in the back seat and removes a beer. How often has Matthau played this character, the lovable slob? (See: The Odd Couple.) And though there is no evidence that his clothing is kept in the trunk, it would be no surprise, after seeing this fellow for five seconds, to discover that this is the case.

Having popped open the fresh brew, he pulls the tab off and chucks it over the side of the car. It lands on the pavement with a tiny but very audible plink. To say it was the plink heard round the world may be an overstatement, yet the whole ethos of an age, really, is contained in the sound of that flimsy piece of metal plinking against the impassive pavement. Hard not to call to mind the heavily creased face of a Native American man (who turned out to be Italian) in that public service ad against littering—hair in braids, a tear running down his stoic cheek. But the creases on Matthau’s own leathery face remain dry as, with a degree of concentration unique to substance abusers setting up the day’s first fix, he pours some beer off the top, and now produces a mostly empty pint of whisky with which he tops off the beer. All to the happy pulsating sound of sprinklers. Registering the first couple of sips as both medicine and ambrosia, he peers out at the unsoiled infield.

The Bears are hopeless, we soon learn, and so is Matthau. But then hope arrives. They improve. In the end the Bears lose the big game but get to pour beer all over themselves. And also drink it.

The real triumph of these kids is having rescued this man from his lethargy and boozy despair, just as he has somehow rescued the kids from their hopeless, self-loathing ineptness. Soulful imperfection is rewarded all around. Everyone on the Bears is a hero, and Matthau— not just coach, but surrogate father—has been resurrected.

Perhaps it was this feeling of paternal resurrection, or at least redemption, that had me coming back to the theater again and again.

__________________________________

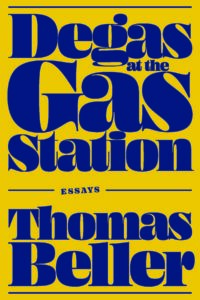

From Degas at the Gas Station: Essays by Thomas Beller. Copyright © 2025. Available from Duke University Press.

Thomas Beller

Thomas Beller is a long time contributor to the New Yorker and the author of several books including Lost in the Game: A Book about Basketball, also published by Duke University Press; J.D. Salinger: The Escape Artist; and The Sleep-Over Artist. A 2024-25 Guggenheim fellow, he is a founding editor of Open City Magazine and Books and Mrbellersneighborhood.com, and Professor and Director of creative writing at Tulane University.