Why I make a very dumb, ranked list of the 100 words I use most every year.

At the end of the last few years, I’ve made a habit of putting together a list of the top 100 words I’ve published most frequently that year. It’s admittedly a strange and arbitrary way to look at a year’s worth of writing, and at first glance, doesn’t really tell you that much about what I wrote. The top 100 are mostly what you’d expect: articles, pronouns, conjunctions, commonly used words, and the odd wild card.

It’s a dumb little project, but one that has become dear to me. Originally I started this as a cheeky way to poke fun at the efficiency-minded, business-y data I saw other writers posting at the end of the year — “I published 267 pieces this year,” “I wrote 203,000 words,” “I was rejected 342 times,” etc. Similar to those computations, the data that my list generates was intended to be pointless, an arbitrary way to evaluate a year of writing.

But I started to find an unexpected value in it, and what started as a weird bit has become something I look forward to every year. My little top 100 lists are both a reflective tool to look back on a year of writing and a way to look forward to what I want to write in the new year. Like reading a horoscope, these 100 words don’t hold any firm answers, but they’re a lot of fun to examine.

First, a quick note on my process. The most time consuming step is gathering together all the writing I published or produced, and since this year felt longer than most, remembering everything I’d worked on since January was tougher than I’d anticipated. But once I track down all the links and all the “final-draft-REALLY-FINAL” files and made note of drafts left unfinished that I want to return to, I dump all the text into one big document, and strip out all of the formatting, hyperlinks, and punctuation.

(A little PSA: this is a great chance to do a little backing up! Writers, screenshot or print-to-PDF any pieces you don’t want to lose! Websites can disappear in a flash and all you’ll be left with is the memories.)

Then all that text is dropped into a web program that sorts word usage by frequency. There are lots of options — and I’m sure someone with a bit of tech savvy could quickly code a tool to do this — but this year I used this site, which only crashed my browser twice before successfully sorting all the words.

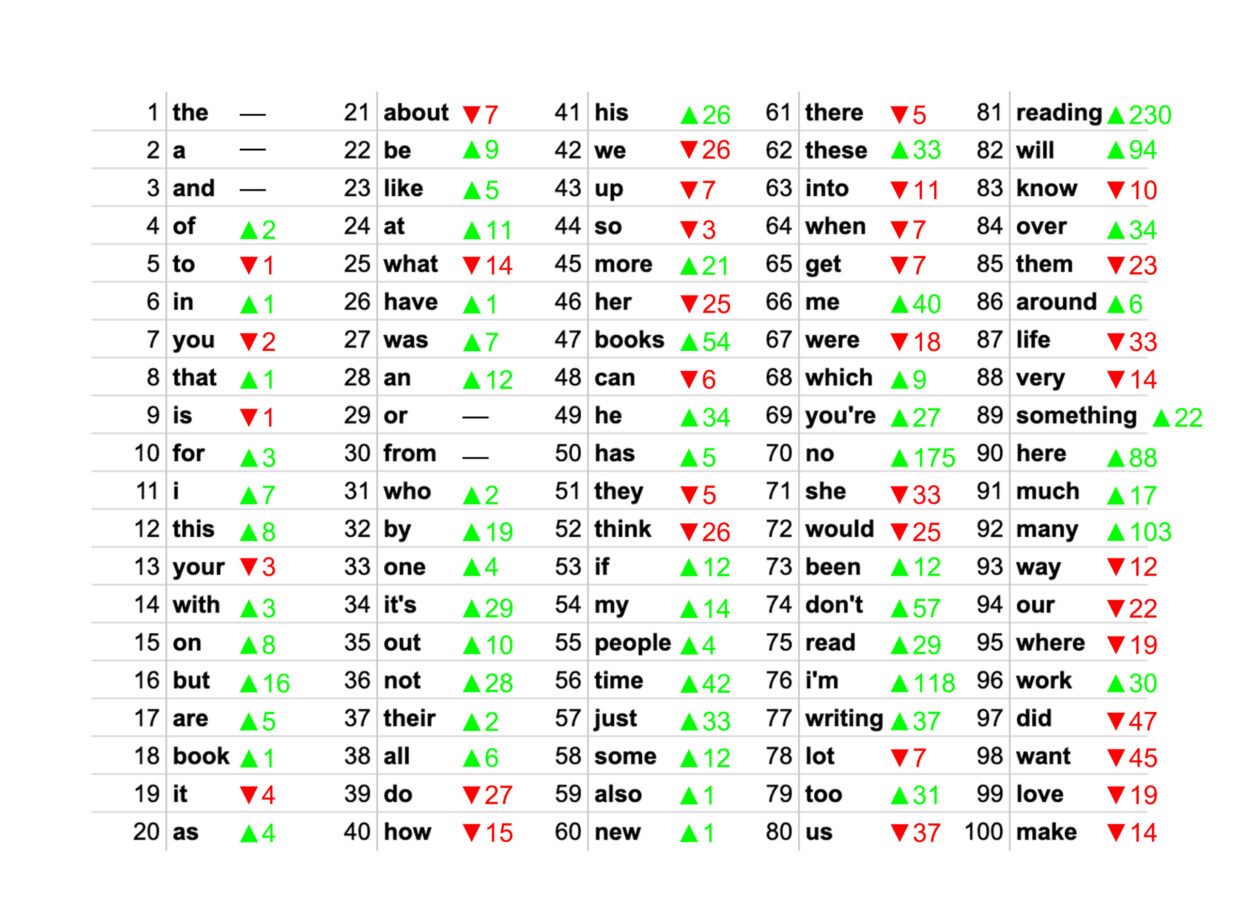

Finally, I take the resulting list over to a spreadsheet, and start poking around. I usually make a little social media friendly top 100 image, and this year I also made a version where I noted how many places a word moved relative to last year’s list:

There’re some obvious takeaways: “the,” “a,” and “and” are holding rock solid in the gold, silver, and bronze positions — hats off to the unsung workhorses of English. And overall there’s not a ton of movement in the top 20, which always remains pretty stable — more “but”s though, maybe I was more contrarian last year?

2024 is also when I started writing blogs for Lit Hub, so my usage of first person pronouns and “book” (#18), “books” (#47), and “reading” (#81) shot up.

I also like using this to track how well I managed to avoid my writing crutches, the words and phrases that I habitually overuse. For me, these are the em-dash, to which I am helplessly addicted, the phrases “I think…” and “to be sure…”, and the word “just,” which came in at #54, up 33 places from last year. I just can’t stop using it.

Looking deeper at the list requires a bit of a meditative approach. 2024 was a year with relatively little “hate” compared to “love” (#1521 and #99). There was more “good” than “bad” (#115 and #271), more “real” than “fake” (#203 and #1988), more “you” than “me” (#7 and #66).

But “work” (#96) was up 30 places — am I too focused on the grind? Is “life” (#87, down 33) passing me by? Perhaps I’m becoming too self-centered: “Me” (#66) and “I” (#11) moved up, while “we” (#42) and “us” (#80) moved down.

When I posted this list on social media a lot of people rightfully pointed out that I used “he” (#49) much more than I used “she” (#71), and male pronouns trended up while female pronouns trended down. Recognizing this stung, but it’s the sort of thing that’s helpful in thinking about the coming year’s writing: how can I be more thoughtful and intentional about who and what I’m writing about in 2025?

In short, what words do I want to see in the top 100 of 2025? If words are how we reflect our inner selves to others, I can look at this arbitrary ranking of words as an imperfect reflection of myself. Do I like what I see? And how can I take steps to improve it?

Again, there are no concrete truths here, and measuring a year of writing this way is akin to measuring a trip to visit an old friend by step count. Ultimately what is contained in the list is less important than my reactions to it, like making a decision by coin flip and knowing in an instant, as the coin floats in the air, how you hope it will land.

James Folta

James Folta is a writer and the managing editor of Points in Case. He co-writes the weekly Newsletter of Humorous Writing. More at www.jamesfolta.com or at jfolta[at]lithub[dot]com.