Why I Give My Books Away For Free

Shane Hinton Won’t Let Money Stand in the Way of a Potential Reader

In 2015, after the release of my first book with Burrow Press, a small press based out of Orlando, Florida, I was invited to give a reading at a public library. The book I’d always imagined I could write was real, and out in the world. I had a box of copies that my publisher had given me to sell, a credit card reader, and a zippered bank bag with a small assortment of bills so that I could make change.

On my drive across the state I’d worried about the books in my trunk. They were so precious to me. What if a car rear-ended me, deforming the trunk, bending their covers and pages? What if it rained and the rain leaked past the failing rubber gasket lining the trunk of my fifteen-year-old Toyota Corolla and the water absorbed past the cardboard box and soaked into the pages of the books, swelling them, causing the ink to run?

Standing at the podium in a small side room of the library, I pressed a copy of my book down flat until the spin cracked. I read a story about a car that crashes into the side of a house. In the story, a family, at first terrorized, learns to live with the car, adopting it as part of the living room, ignoring the chaos of the smashed walls and upended furniture it displaced.

Why is it, then, that I felt that to be a real writer I needed the validation of a marketing budget, of wide release in chain bookstores?

The crowd at the reading was small but polite. After the event, a man with his belongings piled around him approached me quietly at the podium.

“I really enjoyed that,” he said, “but I can’t afford one. Can you give it to me?”

I looked at the pile of books my publisher had handed over to me, thinking of the inventory sheet, the little zippered pouch that now contained thirty or forty dollars in cash sales. “I’m sorry,” I said. “They’re not mine.”

The man looked shocked. “It’s your book,” he said.

I shrugged at the man. The rest of the crowd had already left the room. The chairs were still in neat rows. I walked out of the library. Across the street someone had knitted coverings for the trees and benches in the park. I ran my fingers along them as I passed. The yarn was still damp from a rainstorm the previous night. As I walked away, the man came out of the library and yelled something at me that I couldn’t understand.

In that moment, I had let money come between me and a potential reader. The thing that I most wanted—to have my work taken seriously, to be enjoyed, even, by someone else—had been prevented by a feeling that now seemed misguided, if not stupid: that I had to be paid for my work.

Back then I would have told you that I wanted to be a small press writer. I grew up around a punk rock record shop and I love the DIY ethos of small press publishing. The truth, though, was that I harbored a secret desire that small press publication would lead to something more prestigious. I wanted the kind of life I imagined writers had when I was a child reading in the shade of a drainage ditch on a strawberry farm. I wanted to be taken seriously, to be invited to fancy parties, to have people recognize me from my author photo.

That has not been my experience as a writer. I don’t even like to go to parties. No one has ever recognized me in public.

Nonetheless, I have a life in the arts. I have been invited to read at bookstores and bars and community spaces. I have met people who have already read my books. I teach writing today at the university level—the best job I’ve ever had, and one I knew I wanted after I took my first fiction workshop with a writer who held the door open for me as a young person and assured me that I could find a place in the literary community.

Why is it, then, that I felt that to be a real writer I needed the validation of a marketing budget, of wide release in chain bookstores?

We are taught that a thing’s success in the marketplace directly corresponds to its value, but any lover of small press books, of street musicians, of graffiti, knows this is a lie. The most beautiful song I ever heard was sung by someone passing the open window of my apartment one spring afternoon. I ran to the window to see who it was, but I couldn’t get there in time. I can’t even remember the words or the melody.

I can’t go back in time and find that man from the library, but I try to atone.

People that connect with us in the right place at the right time change the stories we tell ourselves about who we are. Art is one mechanism of this connection. Sales numbers can’t represent the connective potential of a given piece.

At least one reader has hugged me, telling me that my work helped them through a hard night. I can’t figure a way to represent the fulfillment of that on a spreadsheet, or in a checking account. The relationships we forge with each other transcend measurement.

Most of my publications have been in tiny online literary journals. If someone asks me for work, I do my best to say yes, regardless of where it will end up.

When I challenge that hidden bias inside me, that to be a real writer means to be commercially successful, I find I don’t actually believe it. I tell my writing students that I consider them peers, because if we are trying to get better at this practice then we are all concerned with essentially the same thing. I have been interrogating my work for longer than they have, but we all have to sit down with the blank page and try to say something that matters to someone who might care.

I can’t go back in time and find that man from the library, but I try to atone.

These days, I leave copies of my books in inconspicuous places where they might find readers. I tuck them next to gas pumps and in public bathrooms. I leave a little card inside with my email address. I even leave them places where they are likely to be ruined: on top of a sundial before a thunderstorm; on the shoreline of the beach at low tide.

If someone asks to buy a copy of my book, I give it to them for free. I am far better compensated for the labor of writing by the relationships I have formed with readers and other writers than I am by book sales. Because, for me, the twin acts of reading and writing are too sacred to be commercialized. I can’t try to sell someone something while having an honest and vulnerable exchange. And honesty and vulnerability from others has gotten me through the hardest days of my life. I can only hope that I might be able to give someone else that same grace.

I love my life as a small press writer. I’m not likely to ever be the kind of writer whose books you buy at the airport, but my publisher is one of the best friends I’ve ever had. We’ve worked together for a decade, making books that I believe in. And I’ve learned what really matters to me: the possibility that I might live alongside someone else for a few pages, that together we might come to understand ourselves better than we ever could alone.

__________________________________

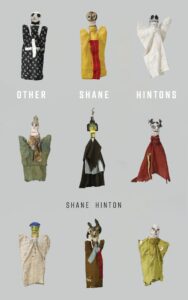

Other Shane Hintons by Shane Hinton is available from Burrow Press.

Shane Hinton

Shane Hinton is the author of the story collection Pinkies and the novel Radio Dark, and editor of the anthology We Can't Help It If We're From Florida. He teaches writing at the University of Tampa and lives in the winter strawberry capital of the world.