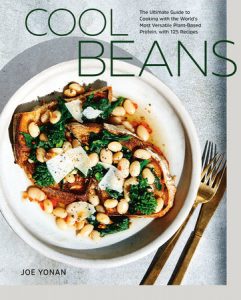

Why Have Humans Always Loved... Beans?

Joe Yonan on the Seductive, Universal Appeal of a Good Bean

“We’re just here for the beans.”

That’s what we told the waiter at Maximo Bistrot in Mexico City, where my husband, Carl, and I were honeymooning.

We had considered a handful of destinations, but CDMX was at the top of our list for several reasons: we had scored cheap nonstop flights from Washington, DC; Carl had never been and I was eager to show him just what he had been missing; and what he had been missing, more than anything else, was the food.

For me, the appeal goes even deeper: Mexico City is not just the capital of our vibrant, fascinating neighbor to the south. It’s the seat of a culinary culture ruled by three kings: corn, chiles, and beans.

And as a longtime vegetarian who reveres beans as the most important plant-based protein in the world and as someone who grew up in West Texas, immersed in Mexican-American culture, I consider Mexico the bean-all and end-all. Every Mexican chef I’ve ever met has waxed poetic about them: scoops of frijoles borrachos (drunken beans) nestled in fresh corn tortillas; complex stews made from slowly cooked black beans, fresh and dried chiles and the pungent herb epazote; and smoke-kissed purees slathered on fried masa boats, topped with lime-dressed greens. It’s one of the many reasons I’ve always felt at home there.

“Though all great agricultural societies have their own staple starch . . . beans are perhaps the one food common and indispensable to all.”

This time, I knew that on and among our visits to the floating gardens of Xochimilco, Frida Kahlo’s and Diego Rivera’s homes and museums, street food tours, art galleries, and markets, I would be on a mission to taste as many bean dishes as I could find. And in my research, one chef emerged as the bean whisperer: Maximo owner Eduardo “Lalo” Garcia. I had heard that he was passionate, with a fascinating background, and that he served a spectacular bean soup at his tasting-menu restaurant.

We got to Maximo an hour before our reservation, just so we could talk to Garcia about beans, which, no surprise, are one of his favorite subjects. In addition to his history lessons about them, Mexican cooking, and the impact of NAFTA on his country’s culture, he described his “very, very old-fashioned” soup, made with beans he gets from the state of Hidalgo. They’re called cacahuate, because they resemble peanuts when raw, but . . . he was fresh out.

Out? I’m sorry, what? We had come all that way to see the master of beans in the world capital of beans only to be told . . . no dice, no beans. A young Los Angeles chef had visited just a day or two earlier, Garcia explained, and he had sent her home with the rest of his stash. I had a hunch: “Was it Jessica Koslow from Sqirl?” He nodded, laughed that I would, of course, know all the other American bean obsessives, and then, when he saw my face fall and recognized the depth of my disappointment, he turned serious. He started scrolling through his phone, I assumed checking emails, texts, or calendar reminders. Good news: He was scheduled for another bean delivery that weekend. He hadn’t planned it, but he’d make the soup for us— that is, as long as we would still be in town and could return.

We would, we could, and we did. A few days later, as we sat down for lunch—the only customers in the place getting just the bean soup rather than the multi-course tasting menu—the anticipation started nagging at me. How good could these beans actually be?

The waiter brought us two big bowls of soup: the beans were super-creamy and golden in color, fatter than pintos, with a broth that was so layered and deep and, well, beany, that it made me swoon. It seemed so simple—just beans and broth and pico de gallo—that I could hardly believe how much flavor I was tasting. My husband, still recovering from a bout of Montezuma’s Revenge, seemed to come back to life before my very eyes. We tore into a basket of blue corn tostadas, and I slugged a Minerva beer in between spoonfuls of the soup. We left happy and restored.

Such is the power of the humble bowl of beans.

*

As a category of food, beans are old, ancient even. Forward-thinking cooks have been talking about ancient grains for years now—my friend Maria Speck helped popularize the idea in her book Ancient Grains for Modern Meals—but some beans are just as old as grains. According to Ken Albala’s masterful 2007 book Beans: A History, among the first plants domesticated, some 10,000 years ago, were einkorn wheat, emmer, barley—and lentils.

Lentils are so old that people who say lentils are shaped like lenses have got it backward; the world’s first lenses got their name because they were shaped like lentils. That’s old. In fact, there’s evidence that thousands of years before they were domesticated, in 11,000 BC, people in Greece were cooking wild lentils.

Pythagoras talked about fava beans, Hippocrates about lupinis, and one particularly famous orator is even more deeply connected to chickpeas: His family took its name (Cicero) from the legume’s genus (Cicer). Ancient Indian rituals and early Sanskrit literature feature mung beans. In the New World, the remains of beans were found in a Peruvian Andean cave dated to 6000 BC. Mentions of black beans show up in the writings of ancient Mayans. A little younger is the soybean, but it has made up for lost ground by becoming, as Albala writes, “the most widely grown bean on the planet, the darling of the food industries and genetically one of the most extensively modified of all plants.”

Mexico. India. Nigeria. Israel. China. Italy. Japan. Spain. The United States. Morocco. Peru. It’s hard to think of a country where beans aren’t part of the culinary fabric.

So why do beans have, well, something of a fusty reputation, especially here in the West?

I think a couple of things are going on: first, there’s the unavoidable association with hippies, the memories of three-bean chilis stirred by pot-smoking countercultural types. But perhaps more importantly, beans worldwide have almost always been associated with poverty. (An exception is India, where the prominence of vegetarian eating ensures that beans have been appreciated by the highest castes.) America, as a relatively young country built on grand ambitions and looking for inspiration, perhaps has historically paid more attention to the cooking of the world’s elite and less to the cooking of the more resourceful lower classes.

That’s been changing, thankfully. As immigrants continue to shape American cuisine and we pay more attention to our own native traditions, we’ve started to realize just how deep the roots of bean cookery go.

Mexico. India. Nigeria. Israel. China. Italy. Japan. Spain. The United States. Morocco. Peru. It’s hard to think of a country where beans aren’t part of the culinary fabric. When Lalo Garcia was growing up in a farming village in Guanajuato, he said, “The one thing we always had in the house was a big clay pot of beans.” Indeed, the incredible cuisine—or as the great Mexican-cooking authority Diana Kennedy puts it, cuisines plural—of Mexico owe everything to the triumvirate of beans, corn, and chiles.

Ran Nussbacher is co-owner of Shouk, a plant-based, fast-casual Middle Eastern restaurant with two locations in DC. With falafel, a fantastic veggie burger, an “omelet” made of chickpea flour, and more, “We are bean heavy,” he says.

In Tel Aviv, where Nussbacher grew up, falafel and hummus were the first, second, and sometimes only, order of business most every day of the week. When he was in the army, stewed chickpeas mixed with rice was a staple. And when he would meet friends for drinks, “The bar always had small bowls of warm chickpeas with a small amount of chickpea water sitting out, heavily seasoned with salt, pepper, sometimes a little cumin, and you’d pick them up with your fingers as you drank beer.”

Ozoz Sokoh, who writes the Kitchen Butterfly blog from her home in Lagos, says beans are “central to Nigerian food culture.” In Lagos, the streets abound with women selling akara, a black-eyed pea fritter. “If you take a poll, almost everyone eats akara on Saturday mornings.” There’s also ewa riro, stewed black-eyed peas with spices; moinmoin, a steamed black-eyed pea pudding somewhat akin to a Mexican tamal; ewa aganyin, a slow-cooked bean stew topped with a black chile sauce and often paired with a soft bread; and more.

India is another great bean-loving culture. Lentils, chickpeas, split peas, and mung beans are used not only to make the great dals and South Indian dosas (page 135) but also such bean-and-rice dishes as khichdi (page 179). “You can’t argue with legions of Indian cooks,” says Priya Ammu, who grew up in India and owns the restaurant DC Dosa. “I loved khichdi growing up. We always had it with cucumber raita and roasted papadums on Sundays.”

What made beans so ubiquitous?

As Albala writes, “Though all great agricultural societies have their own staple starch . . . beans are perhaps the one food common and indispensable to all.”

For much of the world, they have always been a way to sustain through times of poverty, as the cheapest (by far) source of protein around. And now, with a growing interest in plant-based eating even among people who can afford to eat whatever they want, beans have become more appealing than ever.

They are truly unique, as the only food that can be categorized, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), as both a protein and a vegetable. What’s more, according to a 2016 study published in the journal Food & Nutrition Research, meals based on these vegetable proteins are more satisfying than those based on animal proteins. The list of beans’ health benefits is long: they’re nutrient-dense, rich in cancer-fighting antioxidants and heart-healthy fiber, and they have been shown to help improve our gut health, help stabilize blood sugar, and possibly even lower cholesterol.

If there’s one idea that best summarizes their health benefits, it’s this: eat beans, live longer. It’s more than just a fun thing to say. The idea has a basis in some of the most intensive research around longevity of the past few decades. I’m talking about the “Blue Zones” project, in which Dan Buettner and his fellow researchers identified and studied the habits of people in five populations around the world who live significantly longer than average. They share many habits in common—daily exercise, strong social connections, family commitment, moderate alcohol intake—but the one that jumped out at me when I first read about the project was this: the cornerstone of all their diets is beans, about 1 cup per person per day. When Buettner was asked on The Splendid Table radio show what dietary takeaways the rest of us could gather from his project, his response was, you guessed it, “Eat more beans.”

________________________________________

Reprinted with permission from Cool Beans: The Ultimate Guide to Cooking with the World’s Most Versatile Plant-Based Protein, with 125 Recipes by Joe Yonan, copyright © 2020. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Joe Yonan

Joe Yonan, author of Cool Beans, is the two-time James Beard Award-winning food and dining editor of The Washington Post. He is also the author of Eat Your Vegetables, which was named among the best cookbooks of 2013 by The Atlantic, The Boston Globe, and NPR’s Here and Now, and Serve Yourself, which Serious Eats, David Lebovitz, and the San Francisco Chronicle named to their best-of-the-year lists. He was editor of America The Great Cookbook, a project to benefit the charity No Kid Hungry. He writes the Post’s “Weeknight Vegetarian” column and for five years wrote the “Cooking for One” column, both of which have won honors from the Association of Food Journalists.