Why Hardcover is the New Vinyl

Yahdon Israel on the Irreplaceable Magic of Tactility

Heading home on the train from class one night, a college friend recognized me and walked over. We did what many New Yorkers do when they see a familiar face in transit: played the situation up like it was something wanted rather than something that could be done without. I told my friend it was good to see him. He tried to remember the last time he saw me. We asked each other about old classmates, what they’d been up to since graduation—and all the other mundane small talk you make when stuck on a train car. Then, looking down at the black leather Polo duffle stationed between my legs he asked:

“What’s in there? A body?”

“Books.”

He thought I was being sarcastic so I knelt down and unzipped the duffle as if I was trying to sell him something on the low. “See? Books.” I was hoping this would be enough to end the conversation, but it was just beginning.

He asked if the books were for class. I told him they weren’t. He asked if I was selling them. I told him I wasn’t. He asked why I had so many.

“Because I’m reading them.”

“All of them?”

“Yes.”

“Why carry them all? Why not just get a Nook or a Kindle?”

I stared at him for what felt like two stops before I realized the train was actually stuck between stations. Seeing that he was sincerely curious, and knowing that “There’s train traffic ahead of us, we’ll be moving shortly” meant we’d be stuck there for at least another 15 to 20 minutes, I decided to answer. A little bit out of boredom, a little bit out of exasperation. But when I began explaining I realized that I had few answers for him.

With the hope I’d find my way to those answers I didn’t have, I started with the ones I did. Despite claims that technology can bring us closer together, there’s always been something about screens—whether they’re sensitive to touch, stylus, or voice command—that feels impersonal to me. Maybe it’s because no matter what you do on a device—read, watch movies, porn, text, snapchat—the device itself never changes. The screen is always there, a barrier between you and that thing you want to touch, that thing you want to be closer to. But it’s the things we can feel that connect us. Those connections are what make us real to each other.

This is why I carry so many books in my duffle: I want to feel as connected as I possibly can to the world around me. Having all that weight, the weight of so many books, reminds me of this. It reminds me of the burden of the body, and my responsibility to carry it. The weight also reminds me that I’m holding up more than just myself, but others as well. On any given day I can have four or five books in my bag. And while it might be easier to carry all these books on a device, I fear doing so will come at the expense of forgetting these things. The weight keeps me grounded. It reminds me that instead of turning up and tuning out, I should be looking to open up and turn anew, as I would with the pages of the many hardcovers I carry with me.

There’s something gratifying about being able to underline a sentence or write a response in the margin of a book, knowing with certainty that it will be there later. I can’t get that guarantee from a phone. My data could be hacked, a new upgrade could wipe its memory, my battery could die mid-sentence and cause me to lose everything I’ve typed. They say that what goes up into the Cloud must come down, but “they” can’t always be trusted—least of all with the things I value most, my books.

Before the duffle bag, I once bought a copy of Margo Jefferson’s On Michael Jackson on Nook. I already owned a paperback copy, but I decided to buy the digital version to see what “they” had all been saying about technology making my life easier. Within two days I’d forgotten my password, unable to remember which character I had caps-locked and where the underscore went. When I tried reconciling this minor mistake, I was greeted with a security question I didn’t even remember answering: “The name of my first dog? The fuck? I never even had a dog.” I called customer service and waited for close to 30 minutes as they verified my identity and reset my password. When I finally got back into my account, On Michael Jackson was no longer in my library. I had to download it, again. Swiping my screen to page through the digital copy, I looked for traces of my original interactions with the text, but nothing was there. It was like I had never read it.

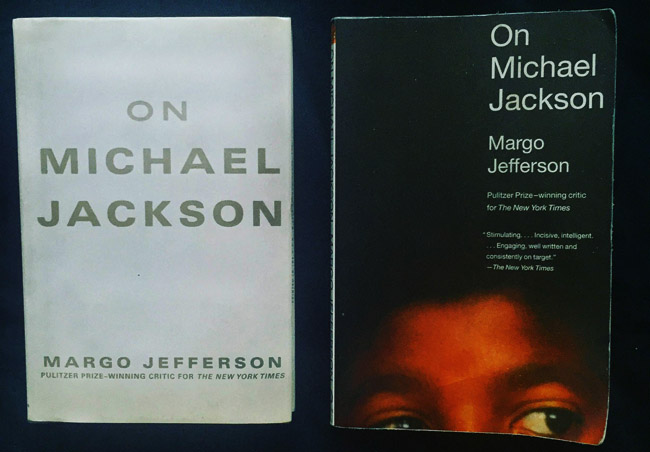

That same night I went to the Strand and asked, out of pettiness, if they had another copy of On Michael Jackson. I wasn’t expecting them to have it, but I wanted to prove that what had happened with my Nook would never happen again. If they did have it, I would own two copies of the same book. Much to my surprise, I was handed a copy of the book that looked nothing like mine. Suddenly, I began to understand what music lovers must feel like when, after spending hours digging through crates at hole-in-the-wall record stores, they finally locate that 12” vinyl they never thought they’d find: I need this.

Of course, you could buy a record like that on iTunes, or stream it on Pandora, Tidal or Spotify, but it’s a deeply satisfying experience to hold something in your hands that you actually went to look for. To know that few people will ever appreciate what you went through to get what you now have. That’s how I felt holding that first edition hardcover copy of Margo Jefferson’s On Michael Jackson. I need this. More than need, I deserve this. Of course it was true that the paperback had the same text, the same revelations on the inside—but sometimes what’s on the outside matters too.

It mattered to me that the hardcover’s sleeve was white with embossed silver lettering I could feel with my fingertips. It mattered to me that, if I wanted to, I could remove the sleeve and I’d still see the grooves of that lettering—not on the cover, but on the spine. And it especially mattered to me that this was a first edition. I may have been late to the party, but I hadn’t missed it altogether. Though I loved that my paperback featured the top half of a young Michael Jackson peeking over the bottom cover of the book—his fro providing the backdrop—it didn’t carry the same weight. It didn’t feel as real. I could bend it; I could fold it; I could do too many things to it without ever understanding what I had done. But I was conscious of that hardcover from the moment I touched it. I was aware of its weight, its burden, and the responsibility it demanded of me. And I bought it—for $10.89. I could’ve picked it up at Amazon for less. I could’ve borrowed a friend’s copy and just not returned it. Hell, I could’ve stolen it from a library. But it was the search that made it mine. It was the search that made it worth it.

Whether in a duffle or a tote, I carry a lot of books in my bag because I’m always looking for more weight to carry, more reasons to feel, more reasons to touch, and more reasons to connect.

As the subway conversation with my friend came to an end, I realized that my books had achieved this, and I knew that his questions had been worth answering. They just came at the expense of missing my stop.

Yahdon Israel

Yahdon Israel writes about race, class, gender and culture in American society. He is currently attending The New School for his MFA in Creative Non-Fiction. Bed-Stuy till he dies.