Why Exactly is This Book Obscene? (Skip to the Dirty Bits)

Why Famous Works of Literature Were Challenged in Court

Plenty of books have been banned or censored over the years—and even more attempts have been made to ban and censor them. But I’ve always wondered exactly what these books were brought to trial for. “Obscenity,” after all, is a pretty wide field. It’s obscene, the number of things I’ve called obscene. So what was it? A certain number of bad words? General sexiness? A queasy feeling in the gut by a well-connected reader? I tracked down a few answers for famous books deemed (by some) obscene. Mostly, it’s about bad words—but sometimes it’s also communism!

D.H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Lover

In 1960, Penguin Books was prosecuted under the UK’s Obscene Publications Act in order to prevent them from publishing D.H. Lawrences’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. This book is famously sexy—just ask the girls in the secretarial pool—but the question at hand was: is it also literature?

The opening address given by the prosecution’s Mervyn Griffith-Jones is now famous. “Let me emphasize it on behalf of the prosecution,” he began. “Do not approach this matter in any priggish, high-minded, super-correct, mid-Victorian manner. Look at it as we all of us, I hope, look at things today, and then, to go back and requote the words of Mr. Justice Devlin ,’You will have to say, is this book to be tolerated or not?'” He went on to argue that the novel is likely to “induce lustful thoughts in the minds of those who read it,” and also that it “sets upon a pedestal promiscuous and adulterous intercourse. It commends, and indeed it sets out to commend, sensuality almost as a virtue. It encourages, and indeed even advocates, coarseness and vulgarity of thought and language.”

Griffith-Jones set this question to the court: “would you approve of your young sons, young daughters—because girls can read as well as boys—reading this book? Is it a book that you would have lying around in your own house? Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?” (This would prove a grave misstep—it was evocative of a time and set of values too far past.)

He also complained of the thirteen “episodes of sexual intercourse” in the book, twelve of these “described in the greatest detail. . . leaving nothing to the imagination.” But it wasn’t only the sex scenes Griffith-Jones counted: “The word ‘fuck’ or ‘fucking’ appears no less than 30 times . . . ‘cunt’ 14 times; ‘balls’ 13 times; ‘shit’ and ‘arse’ six times apiece; ‘cock’ four times; ‘piss’ three times, and so on.” And he took particular issue with the repeated use of “womb” and “bowels”—obviously not the habit of a great writer, you see.

As a witness to the trial put it in The New Yorker, over the course of the proceedings, “practically every description of lovemaking in the book must have been read out by Mr. Griffith-Jones, with awful emphasis and the air of imparting some reprehensible rite that would be news to all his listeners, and it was interesting how well the writing stood up to the treatment.”

Anyway, the defense called 35 witnesses—among them Rebecca West and E.M. Forster—to testify to the book’s literary merit, and Lady Chatterley walked off scot free.

William S. Burroughs, Naked Lunch

In 1962, the book was brought to trial in Boston on obscenity charges, and though Allen Ginsberg and Norman Mailer both testified on the book’s behalf, it lost. The Boston Superior Court ruled against the novel with this statement: “Naked Lunch may appeal to the prurient interest of deviants and those curious about deviants. To us, it is grossly offensive and is what the author himself says, “brutal, obscene, and disgusting.”” However, the decision would be reversed only a few years later by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, which found that, however dirty, the book had literary merit.

For more details on what “brutal, obscene, and disgusting means,” consider this: two weeks after the Boston trial, the book was also challenged in a Los Angeles court, in which the prosecutor pointed out to the Court “that the following words are used in the book a total of 234 times on 235 pages. . . Fuck, shit, ass, cunt, prick, asshole, cock-sucker. Two hundred thirty-four times on two hundred thirty-five pages.”

James Joyce, Ulysses

In 1920, a young girl got her hands on a copy of the literary magazine The Little Review. She was appalled by a specific section—the “Nausicaa” pages of what would be Ulysses, here first serialized—and showed it to her father, who showed it to John Sumner, the secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. This led to obscenity charges against The Little Review, and importantly, charges of violating the Comstock Act, which said that obscene materials were not allowed to be sent in the very dainty and proper U.S. mail.

In court, Sumner argued that the novel was “so obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, indecent and disgusting, that a minute description of the same would be offensive to the Court and improper to be placed upon the record thereof. As Kevin Birmingham explains it in The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses, “the vice society thought that upholding the law meant not examining any of the material the law condemned—the accusation was the evidence. Sumner’s argument was not eccentric . . . but [the judge] insisted on examining the magazine himself.”

In her essay “Art and the Law,” Jane Heap, one of the editors found guilty of violating the Comstock Act, wrote:

The present case is rather ironical. We are being prosecuted for printing the thoughts in a young girl’s mind. Her thoughts and actions and the meditations which they produced in the mind of the sensitive Mr. Bloom. If the young girl corrupts, can she also be corrupted? Mr. Joyce’s young girl is an innocent, simple, childish girl who tends children . . . she hasn’t had the advantage of the dances, cabarets, motor trips open to the young girls of this more pure and free country. If there is anything I really fear it is the mind of the young girl.

. . .

To a mind somewhat used to life Mr. Joyce’s chapter seems to be a record of the simplest, most unpreventable, most unfocused sex thoughts possible in a rightly-constructed, unashamed human being. Mr. Joyce is not teaching early Egyptian perversions nor inventing new ones. Girls lean back everywhere, showing lace and silk stockings; wear low cut sleeveless gowns, breathless bathing suits; men think thoughts and have emotions about these things everywhere—seldom as delicatedly and imaginatively as Mr. Bloom—and no one is corrupted. Can merely reading about the thoughts he thinks corrupt a man when his thoughts do not? All power to the artist, but this is not his function.

. . .

Mr. Sumner seems a decent enough chap . . . serious and colorless and worn as if he had spent his life resenting the emotions. A 100 percent American who believes that denial, resentment and silence about all things pertaining to sex produce uprightness.

Kathleen Winsor, Forever Amber

Forever Amber was one of the best-selling novels of the 1940s, and the fact that it was banned in fourteen states probably has something to do with it. The first of all the states to ban the book was Massachusetts, whose Attorney General, according to Nicole Moore’s The Censor’s Library, cited “70 references to sexual intercourse, 39 illegitimate pregnancies, seven abortions, 10 descriptions of women undressing in front of men and 49 ‘miscellaneous objectionable passages,'” including (in the words of the Customs Minister of Australia, where the book was also banned) “amorous scenes,” “impotence,” “perversion,” “suggestiveness,” “abortion,” and “coarseness.” (If only we could also ban politicians for that last one.) But Winsor herself was nonplussed. “I wrote only two sexy passages,” she said, “and my publishers took both of them out. . . They put ellipses instead. In those days, you could solve everything with an ellipse.”

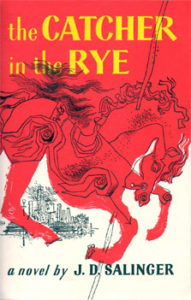

J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

In her book about J.D. Salinger and his most famous novel, Raychel Haugrud Reiff identifies “four main reasons” for the constant censoring of The Catcher in the Rye: bad language, “‘scandalous episodes,'” bad role modeling on the part of Holden, and Holden’s disavowal of “American values.” She notes that “from 1966 to 1975, forty-one attempts were made to keep The Catcher in the Rye out of public education institutions, making it ‘the most frequently banned book in schools’ during these years.” Some examples:

In 1962, a parent in Temple City, California found the language “crude, profane, and obscene” and argued that the novel attacked “home life, [the] teaching profession, religion, and so forth.”

In 1963, parents in Columbus, Ohio asked for the novel to be banned because it was “anti-white.”

In 1972, parents in Massachusetts “claimed that no young person could read this ‘totally filthy, totally depraved and totally profane’ book ‘without being scarred.'”

In 1978, a concerned citizen in Issaquah, Washington, “found 785 profanities and charged that including the novel in the [high school] syllabus was ‘part of an overall communist plot.” By the way, 1984 was also once bizarrely challenged, in 1981 in Jackson Country, Florida, for being “procommunist.”

I also heard that page 32 has no less than 3 goddamns. Salacious.