Why, Exactly, Do We Have Subtitles on Books?

Mary Laura Philpott, Out Here Asking the Tough Questions

Naming a book is a bit like naming a child. The title is the book’s given name, what it goes by. The author’s byline is the book’s surname, which it has in common with every other book by that writer. And the subtitle? It’s the book’s middle name. That is, it’s not what anyone calls the thing, but you’re stuck with it forever, so you might as well pick something good.

As a person who goes by both my first and middle names—“Mary Laura”—I’m extra sensitive to the idea that every part of a name counts. But I admit I didn’t give much thought to subtitles until I started working in the book world several years ago. That’s when I realized some of the most recognizable books on shelves had extra words I’d barely noticed before on their covers. The ubiquitous Eat, Pray, Love was actually Eat, Pray, Love: One Woman’s Search for Everything Across Italy, India, and Indonesia, although I bet no one ever called it that. (When you were in eighth grade and your mom asked you what you were doing your book report on for school, did you say, “Why, I’m reading Frankenstein: Or, The Modern Prometheus”?)

Once a book becomes popular, the subtitle typically disappears from our consciousness. It can be helpful at the beginning, though, especially for memoirs, where the subtitle helps tip readers off to the fact that they’re getting a true story. For example, if you’ve just discovered Belle Boggs’ first book by its title—The Art of Waiting—you might wonder what it is. A novel? A how-to on meditation? A collection of slow-cooker recipes? Maybe a testament to prolonged virginity? But with the subtitle, it all makes sense: The Art of Waiting: On Fertility, Medicine, and Motherhood.

Likewise, Sarah Smarsh’s Heartland is helpfully subtitled A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth. Dani Shapiro’s Inheritance comes with the subtitle A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love. Those work perfectly.

Of course, if you’re an icon whose book will sell based on your name recognition alone, your book can get away without a subtitle. See: Michelle Obama’s Becoming and Sally Field’s In Pieces. Then again, if you’re Michelle Obama or Sally Field, your book hardly even needs a title.

But what if you’re not Sally Field or Michelle Obama?

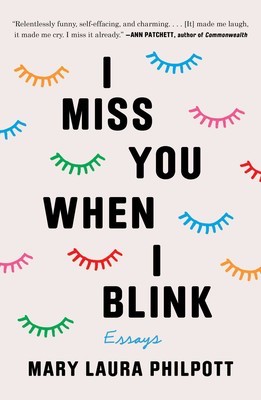

At first, I resisted putting a subtitle on my new book, I Miss You When I Blink. But my agent and editor both felt it needed one. Subtitles are especially important when the title itself doesn’t make much sense on its own, they said, which—OK, fair enough. (I miss you when I what?)

“We’ve been talking about the subtitle here in the office. Now hear me out: what if we went with… Essays?”Nicole Chung’s All You Can Ever Know uses simply “A Memoir” as a subtitle, and I love that grace and simplicity. When I asked Chung about it, she said, “At the beginning we did briefly discuss some other options—some that specifically mentioned race, adoption, birth family, search, reunion, motherhood, etc.—but I hated all of them, because they weren’t really getting at the heart of the book, and who wants to read a list of keywords in a subtitle? Finally, I said I just wanted to go with ‘A Memoir,’ and everyone was fine with that. I worried it might be a marketing problem or something—you know, will anyone know what the book is about?—but it wasn’t at all.”

So, I proposed to my team simply “Essays” or, if we had to get specific about it, “A Memoir in Essays.” What good is a quirky title if you have to explain it all right there on the cover? But no, they said, we really needed something more than that. So I opened up a blank document and started a list: POSSIBLE SUBTITLES.

For weeks that turned into months, I tried to craft subtitles that illuminated the big themes—subtitles that pointed to subtext. I Miss You When I Blink is all about going through life making what seem like the “right” choices, then hitting a point where everything feels wrong. It’s full of the indignities and absurdities that come with small identity crises, the kinds of “what the hell am I doing with my life?” moments you talk about with friends late at night over wine. That’s a lot to cram into a subtitle, but I tried:

I Miss You When I Blink: And Other Things We Tell Ourselves

I Miss You When I Blink: A Life in Glimpses

I Miss You When I Blink: Growing Up, Falling Down, and Starting Over

I Miss You When I Blink: Life as an Imperfect Perfectionist

None of these quite worked. For one thing, I Miss You When I Blink already weighs in at six words. Heaping more words upon it was complicating things rather than clearing them up—not to mention creating a challenge for the cover designer. I kept trying, filling up three pages with ideas, deliriously throwing about such options as:

I Miss You When I Blink: And By “You” I Mean “Me”

and:

I Miss You When I Blink: It’ll Make Sense In a Minute

and, in a moment of defeat:

I Miss You When I Blink: Subtitles Are Hard

Oh God, help.

Then, just as this effort began to feel desperate, as I started to feel sure the very book itself was a terrible idea—because what kind of book just can’t be subtitled?—I got a call from my editor. “We’ve been talking about the subtitle here in the office. Now hear me out: what if we went with… Essays?”

“GREAT IDEA.” I exhaled and placed my forehead on my desk.

I felt simultaneously triumphant at my original wish coming true and—because I am an anxiety-ridden lunatic who can never be satisfied—worried that maybe it was a mistake. Wasn’t this the scenario we were trying to avoid? Did I just have to live with it because I couldn’t come up with anything better? Or is the best subtitle the simplest one, after all?

I sat on the idea for a day, thinking it over. The final essay in my memoir is called “Try It Again, More Like You,” a quote from someone in the story I’m telling, but also a fairly solid summation of the book’s message. It’s OK to fail and start over. Keep trying.

It was right there all along. Sometimes calling the book what it is on the surface is also the most direct route to explaining what it is, deep down.

The word “essay” comes from the French essayer, to try. Every story in this book represents another attempt to get life right. They’re tries. Essays.

I called my editor back: “It’s perfect.”

__________________________________

From I Miss You When I Blink by Mary Laura Philpott. Used with permission of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2019 by Mary Laura Philpott.