Why Ernest Hemingway Makes a Great Subject for

Comic Book Artists

Robert K. Elder on the Protean Appearances of the

Great American Writer

Comic book creators and Hemingway share a natural kinship. The comic book page demands an economy of words, and—for multi-panel stories—a lot of the action takes place between the panels. It’s an interactive reading experience, much like Hemingway’s work. It demands that you interpret and bring yourself to the text, like Hemingway’s less-is-more “iceberg theory,” in graphic form.

In Death in the Afternoon(1932), Hemingway expounded on his theory that what is left out of a story gives it power, that the act of omission strengthens a story. Hemingway contends that in the hands of a talented writer, a reader “will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.” Comic book artists and writers similarly make choices that require both surface and thematic readings, with narrative information being absorbed through a spare, meticulous pairing of text and artwork. Done well, comics are visual experiences that plumb emotional depths.

Hemingway’s influence continues to permeate pop culture, and comics are no exception.

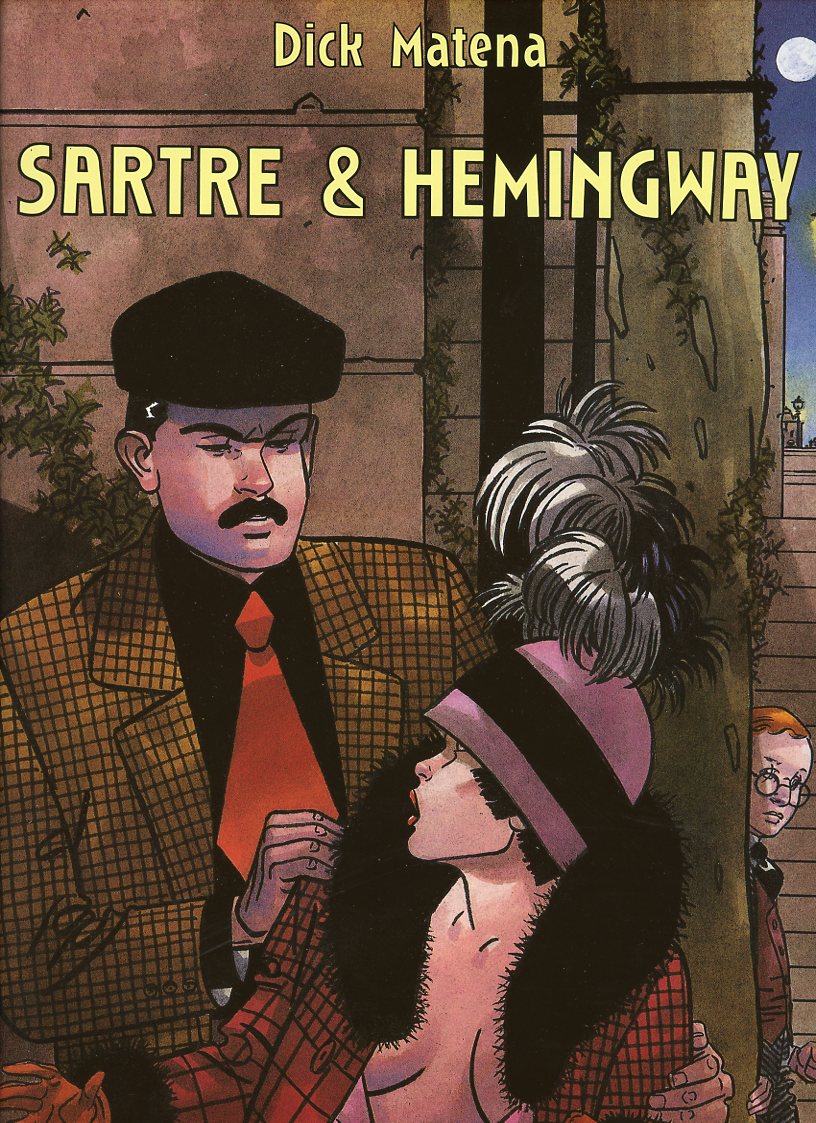

While researching my book Hidden Hemingway: Inside the Ernest Hemingway Archives of Oak Park, I started collecting Hemingway references in pop culture, including more than 40 appearances in comic books. That research turned into several articles for the Comics Journal and the online Hemingway Review. To date, I’ve cataloged more than 120 Hemingway appearances, references, jokes, adaptations, homages, and doppelgängers from across the globe—and the list keeps growing. Even as I write this introduction, a colleague has just sent me a new story starring Hemingway from a comic book artist in Croatia.

Celebrity appearances aren’t new to comic books. Both Stephen Colbert and President Barack Obama got guest shots with Spider-Man, and Eminem got a two-issue series with the Punisher. Orson Welles helped Superman foil a Martian invasion, and President John F. Kennedy helped the Man of Steel keep his secret identity. Even David Letterman got a studio visit from the Avengers. But, using the crowd-sourced Comic Book Database and my own research, I’ve discovered that Hemingway by far exceeds other authors in number of appearances (Shakespeare: 22, Mark Twain: 13). As historical figures go, only Abraham Lincoln comes close to touching him, with roughly 122 appearances in comics (and counting). Hemingway casts a long shadow in literature, one that extends into comic books. In my first wave of research, I found him battling Fascists alongside Wolverine, playing poker with Harlan Ellison, and leading a revolution in Purgatory in The Life After. He has also appeared alongside Mickey Mouse, Captain Marvel, Cerebus, Lobo—even a Jazz Age Creeper.

In comics, the Nobel Prize winner is often treated with equal parts reverence, curiosity, and parody. In 2001, on the fiftieth anniversary of Hemingway’s death, Reed Johnson wrote about how the author’s image had been treated in pop culture. Writing for the Los Angeles Times, Johnson reflected on the “Hemingway caricature handed down to posterity: a hard-drinking, womanizing, big game trophy-hunting, fame-craving blowhard who pushed his obsession about writing in a lean, mean prose style to the point of self-parody.”

The comic book page demands an economy of words, and—for multi-panel stories—a lot of the action takes place between the panels.

Five decades after Hemingway’s death, Johnson observes, “There’s another, more serious and respectable Hemingway still duking it out with this comic imposter in the ring of public perception.”

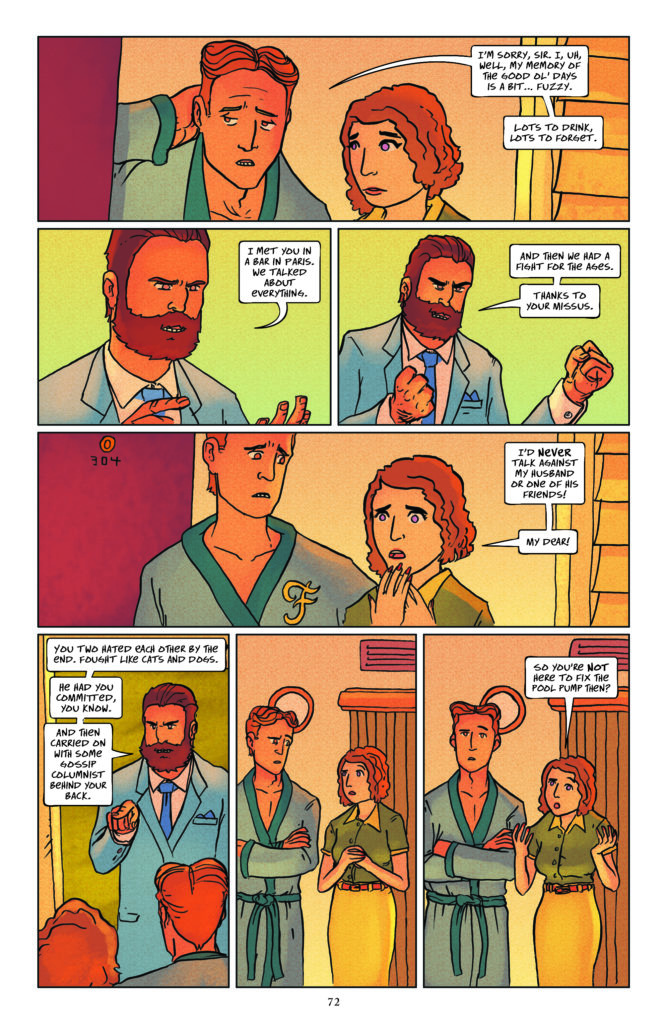

That fight continues and is unlikely to be won anytime soon, because as author Tim O’Brien has pointed out, there is more than one Ernest Hemingway. In the many appearances I found, Hemingway is often the hypermasculine legend of Papa: bearded, boozed up, and ready to throw a punch. Just as often, comic book creators see past the bravado, to the sensitive artist looking for validation. This book endeavors to explore these Hemingway appearances, from the divine to the ridiculous.

When I first presented my research at the 2016 International Hemingway Conference in Oak Park, Illinois, I joked that this project was a pop culture rabbit hole that I couldn’t climb out of. The statement grew truer as I was invited to give talks at universities and to host gallery showings. What I found was a curiosity among fans and scholars about Hemingway and how his legend gets recorded, distorted, parodied, and boiled down to its essential parts.

Hemingway has turned out to be the perfect avatar for comic book artists wanting to tell history-rich stories. He passed through the most beautiful places during the most chaotic times: Paris in the 1920s, Spain during the Spanish Civil War, Cuba on the brink of revolution, France in World War I and in World War II just after the Allies landed in Normandy. He is a fixed point and iconic touchstone that comic book creators love to invent stories around. Even when he’s not the center of the book, a cameo appearance injects the story with energy and pathos.

Although Hemingway was an avid reader of newspapers, he seemed not to linger in the comics section—or, at least, he never wrote about it. His former secretary (and later daughter-in-law) Valerie Hemingway said that while he consumed multiple newspapers, he seemed to skip the comics.

He certainly knew that he was caricatured in his high school yearbook and mentioned in a few single-panel New Yorker cartoons before his death. He was also a consummate doodler; his mother kept some of his cartoonish sketches for his family scrapbooks. He was fond of drawing wine glasses and beer steins in letters, and notably, the teenage Hemingway drew a caricature of himself in a letter to family in 1918 after being wounded in World War I while working for the American Red Cross in Italy. He even includes a word balloon, “gimme a drink,” and points to the 227 pieces of shrapnel taken out of his legs.

The only comic strip to which he was compared in his lifetime, however, was Blondie. After a 1952 visit to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, Howard Berk wrote in National Geographic that Hemingway and his fourth wife, Mary, “seemed to be measuring each other. I had the distinct feeling that she was displeased and that he was trying to figure out what he had done. For some odd reason, the image that came to mind was Blondie and Dagwood, although neither resembled either.”

Comic book artists and writers similarly make choices that require both surface and thematic readings, with narrative information being absorbed through a spare, meticulous pairing of text and artwork.

This was a standard trope in the Blondie newspaper strip: the clueless husband trying to figure out why his wife was mad at him. For the unfamiliar, Chic Young’s Blondie follows the courtship—and later marital conflicts of—bookkeeper Dagwood Bumstead and former flapper Blondie. Young’s iconic couple translated their loving but friction-filled marriage from newspapers into radio, TV, movies, and their own monthly comic books published by Harvey Comics.

There’s plenty of Hemingway the adventurer in the comics discussed in the following pages; there’s also Hemingway the husband, the lover, the writer, the hunter, and a man alone, battling his demons.

A note about organization: I’ve largely kept to a chronological presentation, so it’s easy to track Hemingway’s evolution in comics. I have not differentiated between daily comic strips, like Peanuts and Doonesbury, single-panel New Yorker–style cartoons, and traditional comic books, like Superman. I’ve included comics and illustrations from big publishers (such as Marvel and DC), independents (such as Dark Horse Comics and Fantagraphics), and foreign publishers (Le Lombard, Manga Bungo, Panini), as well as underground, internet, and other self-published comics. In an effort to be more inclusive and expand the scholarship, I’ve also included web comics and the odd subgenre of Hemingway as a portfolio model. While I was searching for images, I kept running into portraits of Hemingway and scenes from his work that weren’t attached to either a book or a web comic. Rather, these commercial or portfolio images were created by aspiring comic book and graphic artists.

This work also includes a few breakout chapters, in which my collaborators offer examinations of Hemingway comics and adaptations. In a couple places I’ve grouped similar sections together, such as Italian Disney comics and the work of Norwegian cartoonist Jason.

Almost all of the interviews in this volume are original, appearing for the first time. In some places, I’ve removed my own questions and let the creators speak for themselves.

It’s worth noting that this is not a complete encyclopedia of Hemingway in comics. That would be an impossible task, as a new work is always being created or found. To paraphrase Paul Simon, Hemingway has not ended up a cartoon in a cartoon graveyard. I see this not as the definitive work on the subject, but the first step.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Hemingway in Comics by Robert K. Elder. Used with the permission of The Kent State University Press. Copyright © 2020 by The Kent State University Press.

Robert K. Elder

Robert K. Elder is the author of 14 books, including Read Your Partner Like a Book, The Mixtape of My Life, and Hidden Hemingway. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, The Boston Globe, the Paris Review, and many other publications. He is the chief digital officer for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and the founder of Odd Hours Media. Robert lives and writes in Chicagoland.