Why Does Losing a Pet Hurt So Much?

Jacky Colliss Harvey on Our Very Human Grieving of Animal Companions

“Where there is grief, there was love.”

–Barbara J. King, How Animals Grieve, 2014

If by some chance you should ever find yourself driving near the village of Loxhill in the southeast of England, you may well start to suspect that you are traveling through the landscape version of a detective story. Here, for instance, is a stretch of boundary wall, just visible from the leafy road—well built, still solid with self-importance; there a run of railings, so old it has rusted a purplish dark. Now you pass what was clearly once an entrance of some importance, complete with gatehouse; and behind it trees dotted across the landscape that show the unmistakable signs of having had livestock browsing beneath them since they were planted maybe two centuries ago, and which now all branch at the same level, just a little higher than sheep or cow can comfortably reach. But where’s the mansion that would make sense of all of this, looking down on the road from one of those tree-crowned hills—and why, in that field beside the road, with nothing around it but trees and rough grass, should there be, rather creepily, a tombstone?

Toward the end of her biography‑by‑dog, Elizabeth von Arnim writes, “This story, like life, as it goes on, is becoming dotted with graves,” and I am afraid this essay is going to be the same. If you have an animal in your life, you can’t get away from the fact that in almost every case, you will outlive them. It’s as true for the tiniest as it is for the biggest and most brave—even the Earl, whose grave here in this Surrey field is now all that remains of Park Hatch and of those who lived there, who very likely had no more serious notion of their own passing from this landscape than did the Earl himself. “HERE LIES ‘THE EARL,’” the stone declares:

HE WAS CHARGER TO R.T.GODMAN IN THE 5TH DRAGOON GUARDS FOR 19 YEARS SERVED THROUGH THE RUSSIAN WAR IN TURKEY AND CRIMEA 1854–6

And here is how he met his end:

SHOT IN CONSEQUENCE OF AN ACCIDENT ON 26TH DEC. 1868 WHEN STILL IN FULL VIGOUR

There’s some comfort in that. No slow descent into decrepitude, just a tragic mishap on what sounds to have been a Boxing Day hunt, and a bullet, presumably where he lay (and where he lies still), but even so. The Earl was not simply a companion animal. Like soldiers and their service dogs in Iraq and Afghanistan, Godman and his horse were brothers‑in‑arms. They had passed together through experiences that set their relationship apart. You can imagine how much Godman must have grieved.

How indeed, we quiz ourselves, can the loss of something so small create a pain so immense?

It is quite stunning, as an owner, how much it can hurt to lose a pet. When Sir Walter Scott’s favorite, a bull terrier named Camp, died in 1809, Scott’s only comfort was that the loss was not more painful: “If we suffer so in losing a dog after an acquaintance of ten or twelve years, what would it be if they were to live double that time?” According to Scott’s daughter, Sophie, at Camp’s burial the whole family stood around the grave in tears, while Scott himself smoothed the turf where Camp lay as if it were a substitute for and as close as he could now come to stroking the dog itself. It sounds like a Victorian version of the final scene in the movie Marley and Me, which in itself is saying something about the universality of the experience and how desolating it can be. The death of a pet can be agonizing to a degree where even as bereaved owner you’re asking yourself how it is possible for it to hurt quite so much. Joachim du Bellay was asking himself this very thing circa 1558, three days after the death of his cat:

I cannot speak, or write

Or even think of what

Belaud, my small grey cat,

Meant to me, tiny creature . . .

How indeed, we quiz ourselves, can the loss of something so small create a pain so immense? “Incomprehensible” was how Jane Carlyle described her sorrow, after Nero finally succumbed to his injuries in February 1860, and at once set about memorializing him in mourning jewelry, much as another woman of her age and class might have commissioned the same for a lost spouse—or child. Indeed, Jane drew the parallel herself: “My little dog is buried at the top of the garden,” she wrote to Mary Russell in February 1860, “and I grieve for him as if he had been my human child.” She was also as vicious as a woman of her age and class might ever have felt herself free to be with those who failed to comprehend the depth of her grief—which, true enough, can be as baffling to the outsider as it is to the owner. “All my other visitors,” she wrote to Lady Ashburton, “have spoken odiously on what they call my ‘little bereavement.’”

They don’t conceive what pain they give me. Three several men, the only men I am intimate with here, offered one after another to “give me another little dog.” And two women, of the sort called “full of sensibility,” inquired if I had “had him stuffed?”

“I wonder you didn’t” said one of them plaintively, “he would have looked so pretty in a glass case in your room, and still been quite a companion to you.” Merciful Heavens! If one lived in what Mr. Carlyle calls “a sincere age of the world,” wouldn’t one take such a Comforter as that by the neck and pitch her out the window?

It causes the sensation that the heart is indeed about to burst, or break, and physical pain extreme and similar enough to an actual heart attack to send one to the emergency room.

Nothing “little” about such bereavement at all. When Linky, Edith Wharton’s final Pekingese, had to be put to sleep in April 1937, her death had so great an effect upon the 75-year-old writer that it seems to have played a part in severing Wharton’s own last ties with the world as well. In her diary Wharton writes of Linky’s ghost standing at the front of all those others she had lost, human as well as canine. After that, the flow of words in the diary she had kept for decades stutters to a halt. Four months later, Wharton herself was dead.

The taxidermy that her visitor was rash enough to suggest to Jane Carlyle—to keep her companion with her in some way, as well as, you could argue, the cloning of pets today—is a measure of how extreme the reaction can be to their loss and how much we dread it. There is a particularly nasty (and, thankfully, rare) syndrome, an acute response to grief, known medically as takotsubo cardiomyopathy—a bulging outward of one chamber of the heart, in response to intense stress, so that the whole heart takes on the shape of a Japanese tako tsubo, or octopus pot. It causes the sensation that the heart is indeed about to burst, or break, and physical pain extreme and similar enough to an actual heart attack to send one to the emergency room. A recent case involved a 62-year-old woman in Texas. There were other stresses in her life, but it was the death of her dog that finally precipitated the physical crisis. Why is the loss of a non-human animal felt so cruelly? What is it that makes the death of such a companion being an experience this profound?

You have to begin with the living relationship to answer that question, and sometimes it is only the end of it, the severing of the bond, that reveals how exceptional it had become. It was the death of Alex, her Avian Learning Experiment, that showed Irene Pepperberg how much more he had become to her than that. She describes how “his passing taught me the true depth of our shared connection,” and most tellingly, she uses the language of human bereavement (“passing”) to do so. When Scott spoke of Camp’s death, it was as that of a “dear old friend.”

Even Pepys, for all he might protest in his relationship with Fancy, was not immune. When in September 1668 he learned of her death “big with puppies” in a letter from his father in the country, to whom the pregnant Fancy had presumably been sent for her confinement (another parallel with the human world), he describes her in his diary as “one of my oldest acquaintances and servants”—not as a dog but as a human equal. Or possibly as even more than that. Sociological studies aplenty support the idea that in our family groups we see the animal members as being more reliable allies and steadier friends than the human ones. Never mind if they truly are or not—the baroque inner wiring of our emotions places such value on this perception that these companion animals end up being literally invaluable to us.

The very language of death where a pet is concerned is all about physical sundering—we pick them up and carry them about in life, but in their death, we “put them down.”

Sigmund Freud, whose consulting room in the 1930s smelled at least as strongly of Chow, those “stodgy teddy bears,” as it did of Freud’s own cigars, believed this was because animals offered, in his famous phrase, “affection without ambivalence . . .an intimate affinity . . . an undisputed solidarity.” So in contrast to the much more challenging and changeable (and more compromised) relationships we have with the other humans around us, there is this steady, reliable, unchanging alliance—and then with the animal’s death, all that emotional stability and security is suddenly removed as well. Even being reminded of the loss can be painful beyond bearing. “Dyed our favourite Cat, Tit,” William Stukeley writes sorrowfully in his memoirs for August 31, 1720, and then adds, revealingly, “my gardner buryd her in Rosamunds bower the pleasantest part of my garden, wh. gave me great distaste to it.” The very language of death where a pet is concerned is all about physical sundering—we pick them up and carry them about in life, but in their death, we “put them down.” Of course our mourning is going to be unambivalent and unalloyed.

But are we allowed to make it public? Perhaps this is another reason why pet death hurts so much and so disproportionately—the fact that unlike other bereavements there’s societal pressure to keep it low-key. Isabella d’Este, on the death of Aura in 1511, might make no secret among her circle of the fact that she expected fully worked‑up poetic elegies for her favorite dog, and receive them, including three from the scholar Carlo Agnelli alone, but this was Isabella d’Este. For the garden-variety owner, much as they might howl in anguish in private, descriptions of their grief nearly always have an apologetic coloring. Two hundred years after Isabella, Lady Wentworth felt she must beg God’s forgiveness for being “more than I ought concerned” about her dog Fub’s death, although the grieving was heartfelt and still took place.

When (an even greater blow) Pug, her monkey, died in 1712, again she wrote, “God forgive me, there is some that bears the name of Christian, that I could have rather had died.” When her son offers her a replacement, she declines on the grounds that she herself is “so great a fool” (“fool” being the term she also uses for her animals) and so “foolishly fond” that such relationships are simply too much for her in her old age. She also speaks of how she forced herself to go about in society, even as she grieved, for appearance’s sake. Walpole nursed Rosette, Tonton’s predecessor, for many weeks in 1773 and divided his friends into those with “Dogmanity,” who would understand and empathize with his distress, and those who would not. When Rosette died, he wrote his own elegy for her (“Sweetest rose of the year”) and sent it to one of the former, disclaiming any literary merit for it but saying that “it came from the heart . . . therefore your Dogmanity will not dislike it.”

Move on by another 100 years, and Grace Greenwood, who had a small necropolis coming into being in a quiet corner of her family garden, records how she had to add to it the pitiful corpse of Jack the drake, who in the course of a singularly accident- prone life had been trapped in a cistern, run into the fire, sustained a broken leg in a rattrap, and who ultimately drowned in a millrace. Grace writes shamefacedly, “It may seem very odd and ridiculous but I really grieved for my dead pet.”What’s foolish or ridiculous about it? We love, we lose, we mourn. It shouldn’t take us by surprise; it certainly shouldn’t be something we feel the need to apologize for.

And just to make the death of a pet even more agonizing, it is so often we who have to be responsible for it.

There is evidence of a change in the general attitude toward pet death, which seems to back up the emergent status of pets being publicly accepted as overt members of the family, as opposed to their being so for their owners alone. In 2016, a number of newspaper reports appeared, listing those companies that elected to give employees time off to mourn an animal’s death. Many owners still feel diffident about asking for such leave, which is understandable—this has been a private grief for centuries—but the fact that now it needn’t be so reflects an increased general acceptance of what for the owner, I believe, has always been the case: losing an animal hurts, and the way you deal with that hurt, as with any other loss, is to grieve and to have that grief recognized. This change in attitude might also be an inevitable result of the increased numbers of pets we are supposed, now, to have living with us. If indeed many more of us encounter this situation, many more of us will know how excruciating it can be.

And just to make the death of a pet even more agonizing, it is so often we who have to be responsible for it. That’s bad enough now, but consider how much more difficult and horrible it would have been to euthanize a pet before the lethal injection from the vet was available. As if Jack the drake’s loss had not been enough, Grace also records how she lost her cat, Kitty, who had her back broken in a bit of roughhousing by Grace’s beloved older brother, and for whom there was no other means to hand to put her out of her agony than beheading by the straw-cutter in the barn. Kitty’s owner hides in her closet and stops her ears (that vivid little detail) “until it is all over.”

Far better, if you had to, if you could, to find a coup de grâce for a pet via a local farmer with a shotgun. This was the fate of Luath, “not ill, only grown old and worn out,” as Mary Ansell offhandedly describes him. Mary had by this time left J. M. Barrie and was living with the poet Gilbert Cannan in a converted mill, where Cannan and their two dogs were painted by Mark Gertler. Luath is on the right; the other dog is Sammy, who according to Mary sat every day on Luath’s grave until he too died, thus displaying, you may well think, rather more distress than Mary herself. And a bullet was all very well if the person holding the gun knew what they were doing, but many did not—thus the American Humane Education Association’s edition of Black Beauty of 1904, which, with the sort of horrid benumbed pragmatism that has to characterize this area of our dealings with our animals, included instructions for shooting both horses and dogs.

The questions of human and animal death brush up against each other, with the death of a pet animal being both a rehearsal for and a lesson in our own.

Otherwise the only quick, sure death was by poison. Louis Wain’s Peter encounters a neighbor who has nine cats, plus the tombstones of five more in his garden, all of them finished off with prussic acid, which would be cyanide to you and me. Nero’s death, in her maid Charlotte’s arms (Jane could not stand to witness it, any more than Ackerley could with Queenie), came about in this way, thanks to the intervention of Jane’s own doctor. Prussic acid or chloroform remained the agents of choice until the 1880s, when a lethal gas chamber using carbonic acid was created at Battersea by Sir Benjamin Ward Richardson (1828–96). Richardson did much to advance human anesthesiology, too, which does at least suggest his heart was in the right place when it came to sparing living creatures pain.

Luath’s predecessor, Porthos, was sent to Battersea Dogs Home once “it became impossible to have him any longer about the house,” as Mary euphemistically puts it, “and in that lethal chamber he was peacefully put to sleep,” or at least so one hopes, but as Mary could hardly have entered the chamber with the poor dog, you have to ask, how would she know? It took just twenty years before the suggestion was made that the same means might remove “defectives” from among the human population. It’s as heartening as it is heartbreaking, after all that, to read Jessica Pierce’s 2012 account in The Last Walk of her struggles with her aging dog, Ody, to find him “a good end”; to put herself, with him, through all the indignities and infirmities of old age for as long as he has enough quality of life left for there to be good moments among the bad—and then when she senses that this balance has been lost, to acknowledge that the good end has been reached, that to extend Ody’s life would not be good any longer, not at all, and to act, at once.

Of course what that “good end” might be, our animals cannot articulate for us—but then many of us will be unable to do so, either, when the time comes. The questions of human and animal death brush up against each other, with the death of a pet animal being both a rehearsal for and a lesson in our own. My father, at 90, and increasingly incapacitated by a series of microstrokes, could not have said what he wanted his death to be, either, but our inability to describe what our own “good end” might be doesn’t mean we won’t know it when we reach it. The difference is that with an animal, the decision so often must be ours, not theirs. And that’s a terrible place for an owner to be. As Ackerley put it, writing of Queenie’s final trip to the vet, “She knew nothing that happened to her; it is I who knows too much.”

__________________________________

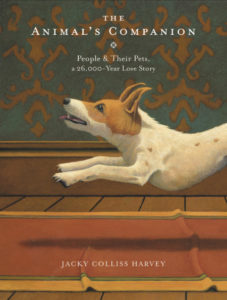

Excerpted from The Animal’s Companion. Used with permission of Black Dog & Leventhal. Copyright © 2019 by Jacky Colliss Harvey.

Jacky Colliss Harvey

Jacky Colliss Harvey is a writer and editor. She studied English at Cambridge University and art history at the Courtauld Institute. She has worked in museum publishing for the past 20 years and is a commentator and reviewer who speaks in both the U.K. and abroad on the arts and their relation to popular culture. Her red hair has also found her an alternative career as a life model and a film extra playing everything from a society lady in Atonement to a Parisian whore in Bel-Ami. She is the author of My Life As A Redhead: A Journal and the forthcoming book The Animal’s Companion. She splits her time between New York and London.